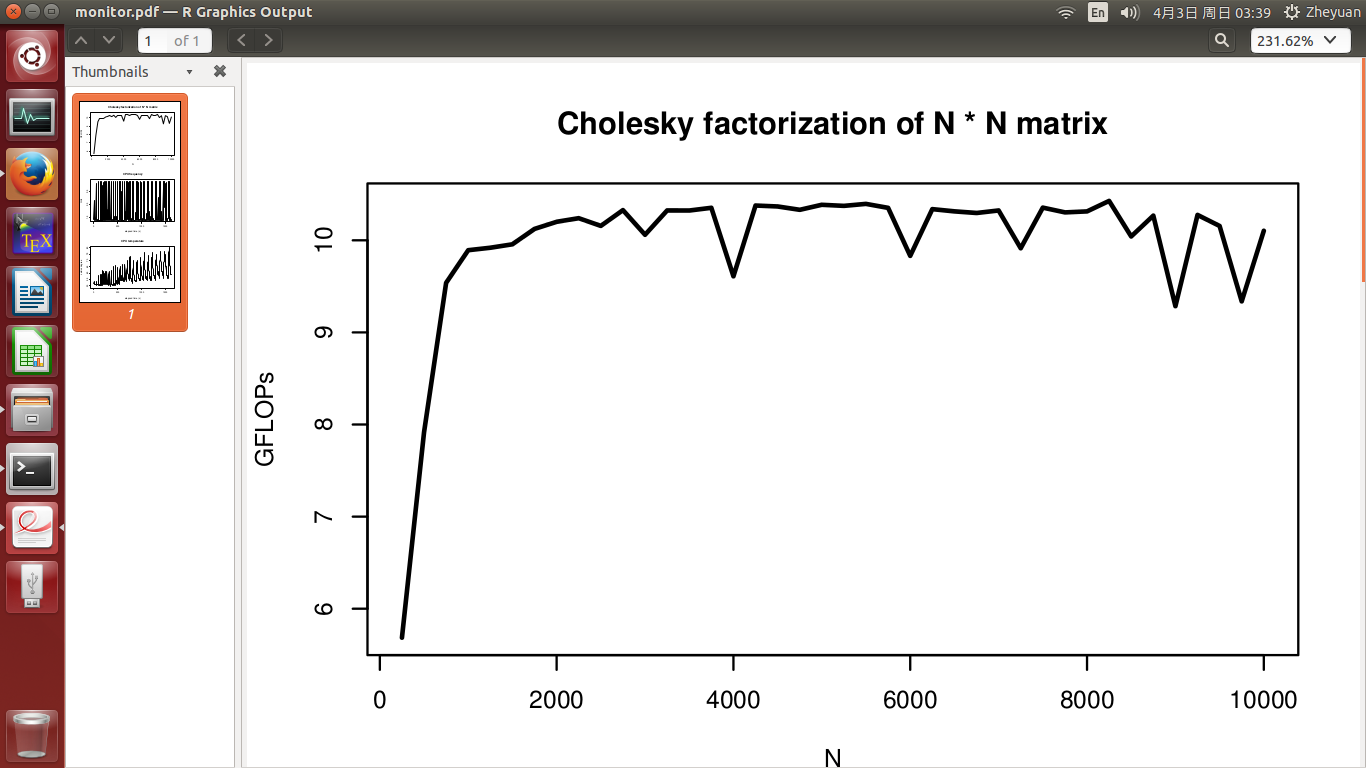

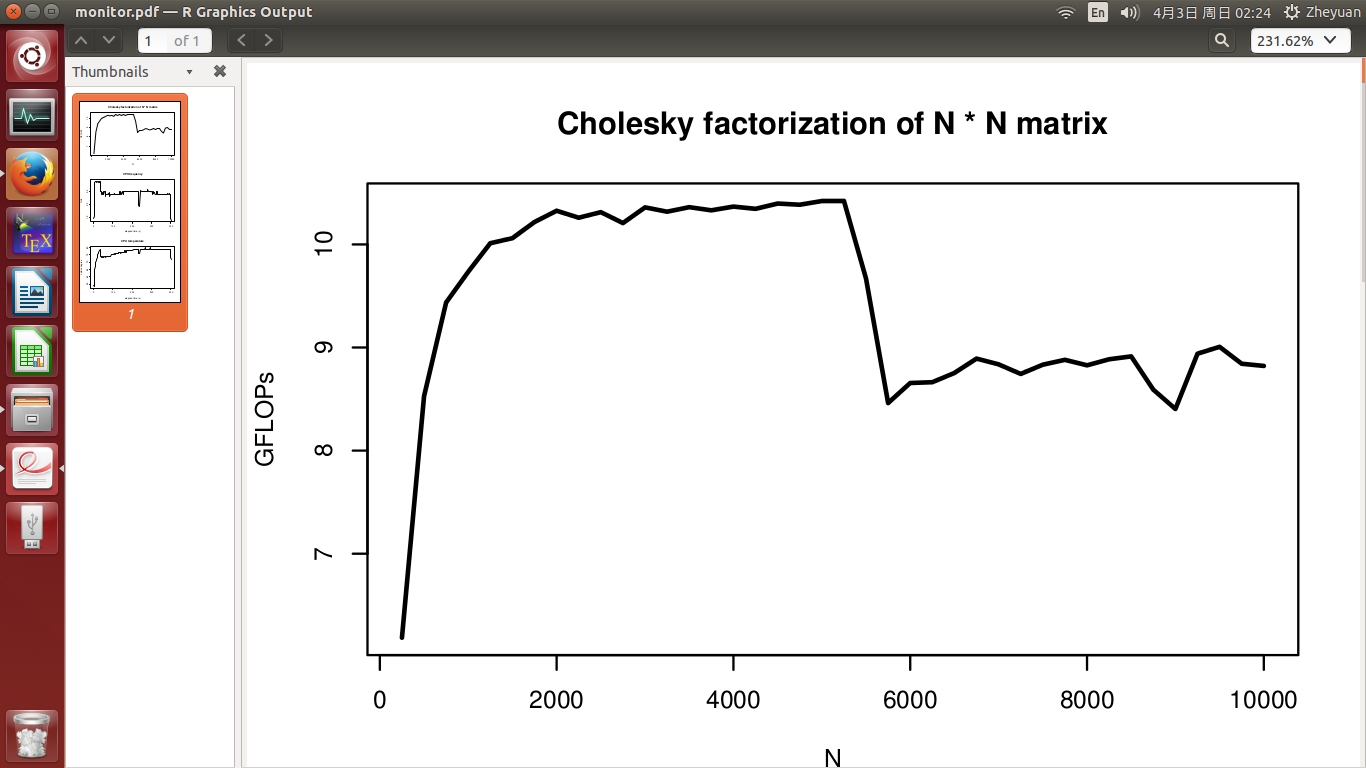

I have developed a high performance Cholesky factorization routine, which should have peak performance at around 10.5 GFLOPs on a single CPU (without hyperthreading). But there is some phenomenon which I don't understand when I test its performance. In my experiment, I measured the performance with increasing matrix dimension N, from 250 up to 10000.

- In my algorithm I have applied caching (with tuned blocking factor), and data are always accessed with unit stride during computation, so cache performance is optimal; TLB and paging problem are eliminated;

- I have 8GB available RAM, and the maximum memory footprint during experiment is under 800MB, so no swapping comes across;

- During experiment, no resource demanding process like web browser is running at the same time. Only some really cheap background process is running to record CPU frequency as well as CPU temperature data every 2s.

I would expect the performance (in GFLOPs) should maintain at around 10.5 for whatever N I am testing. But a significant performance drop is observed in the middle of the experiment as shown in the first figure.

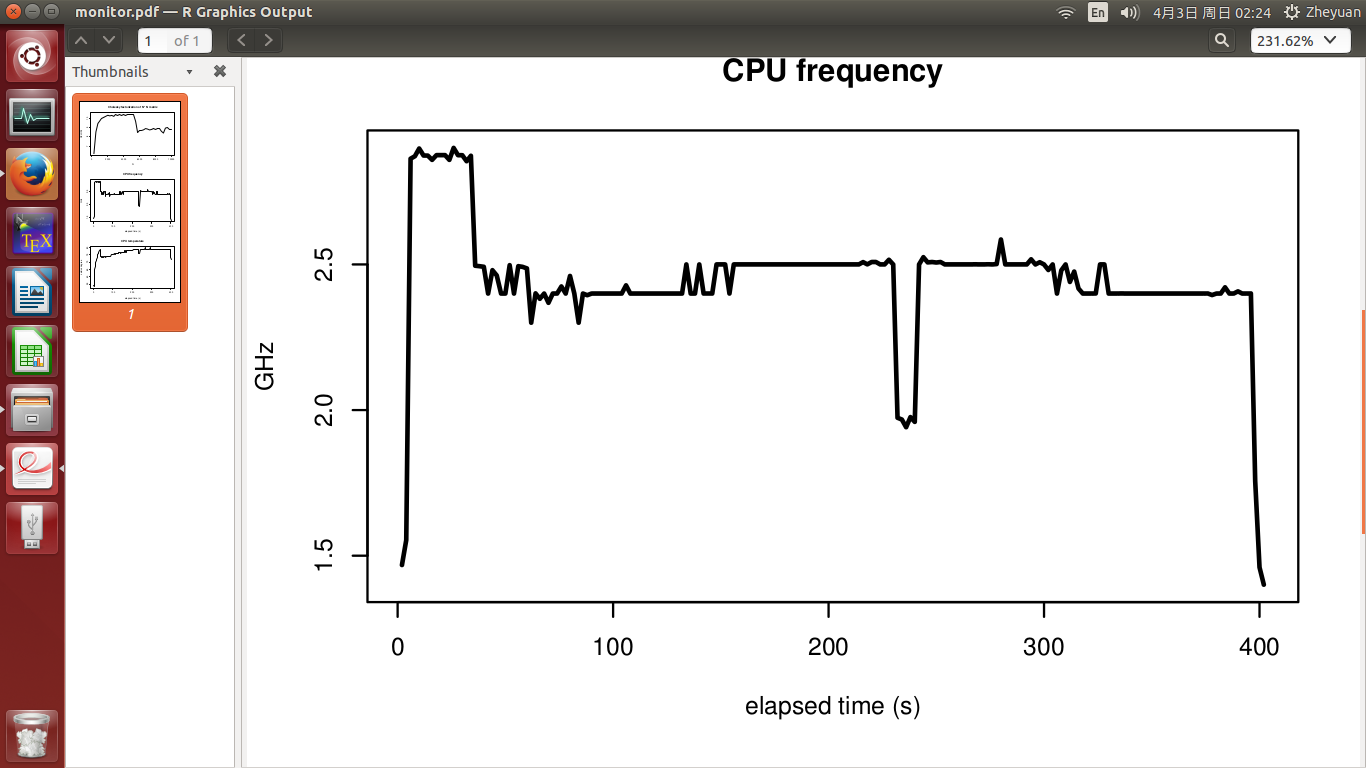

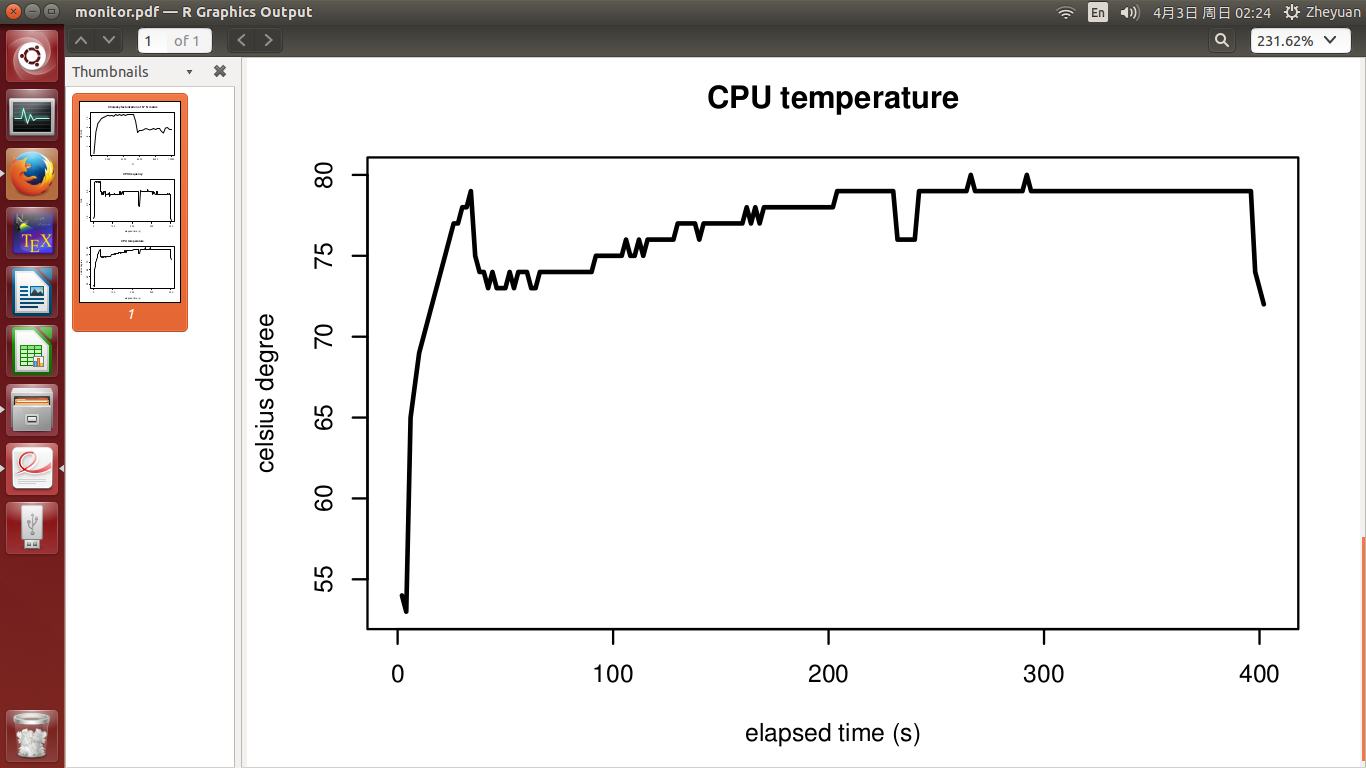

CPU frequency and CPU temperature are seen in the 2nd and 3rd figure. The experiment finishes in 400s. Temperature was at 51 degree when experiment started, and quickly rose up to 72 degree when CPU got busy. After that it grew slowly to the highest at 78 degree. CPU frequency is basically stable, and it did not drop when temperature got high.

So, my question is:

- since CPU frequency did not drop, why performance suffers?

- how exactly does temperature affect CPU performance? Does the increment from 72 degree to 78 degree really make things worse?

![enter image description here]()

![enter image description here]()

![enter image description here]()

CPU info

System: Ubuntu 14.04 LTS

Laptop model: Lenovo-YOGA-3-Pro-1370

Processor: Intel Core M-5Y71 CPU @ 1.20 GHz * 2

Architecture: x86_64

CPU op-mode(s): 32-bit, 64-bit

Byte Order: Little Endian

CPU(s): 4

On-line CPU(s) list: 0,1

Off-line CPU(s) list: 2,3

Thread(s) per core: 1

Core(s) per socket: 2

Socket(s): 1

NUMA node(s): 1

Vendor ID: GenuineIntel

CPU family: 6

Model: 61

Stepping: 4

CPU MHz: 1474.484

BogoMIPS: 2799.91

Virtualisation: VT-x

L1d cache: 32K

L1i cache: 32K

L2 cache: 256K

L3 cache: 4096K

NUMA node0 CPU(s): 0,1

CPU 0, 1

driver: intel_pstate

CPUs which run at the same hardware frequency: 0, 1

CPUs which need to have their frequency coordinated by software: 0, 1

maximum transition latency: 0.97 ms.

hardware limits: 500 MHz - 2.90 GHz

available cpufreq governors: performance, powersave

current policy: frequency should be within 500 MHz and 2.90 GHz.

The governor "performance" may decide which speed to use

within this range.

current CPU frequency is 1.40 GHz.

boost state support:

Supported: yes

Active: yes

update 1 (control experiment)

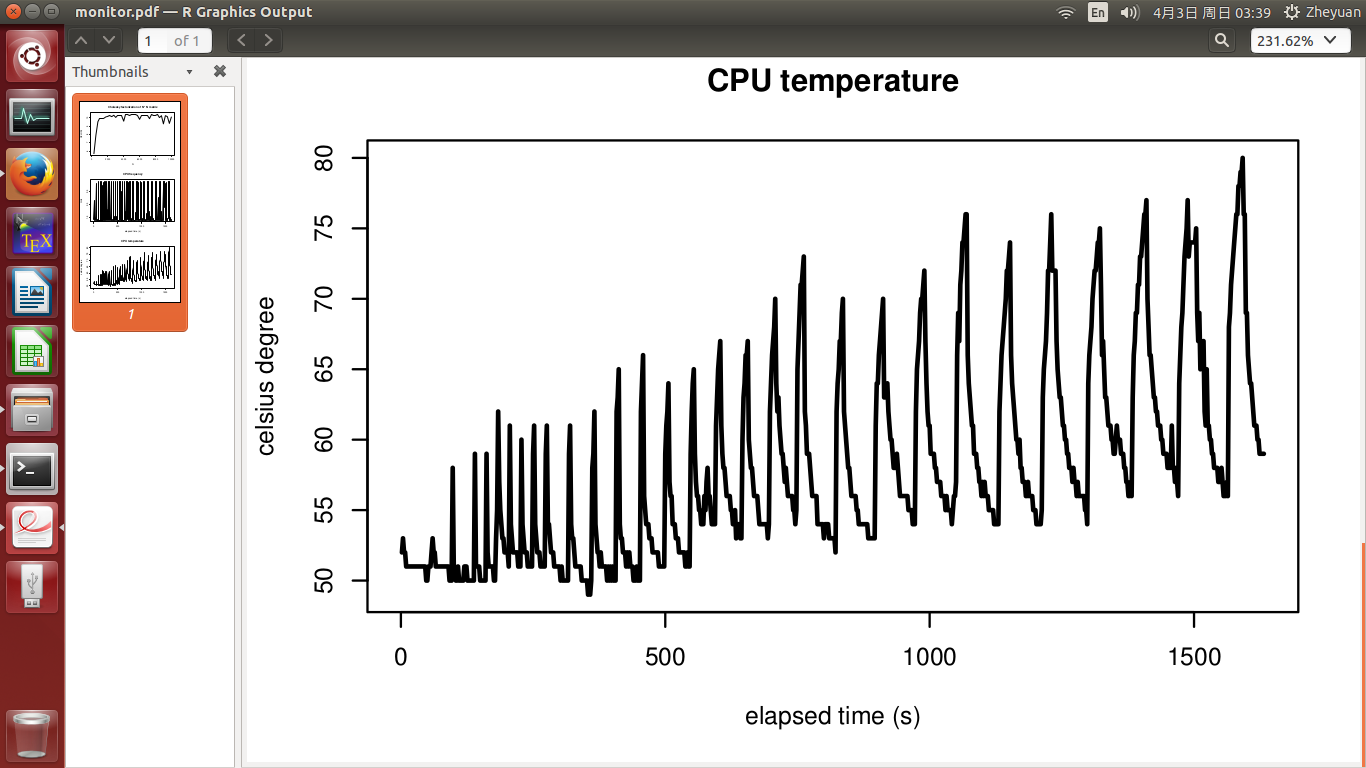

In my original experiment, CPU is kept busy working from N = 250 to N = 10000. Many people (primarily those whose saw this post before re-editing) suspected that the overheating of CPU is the major reason for performance hit. Then I went back and installed lm-sensors linux package to track such information, and indeed, CPU temperature rose up.

But to complete the picture, I did another control experiment. This time, I give CPU a cooling time between each N. This is achieved by asking the program to pause for a number of seconds at the start of iteration of the loop through N.

- for N between 250 and 2500, the cooling time is 5s;

- for N between 2750 and 5000, the cooling time is 20s;

- for N between 5250 and 7500, the cooling time is 40s;

- finally for N between 7750 and 10000, the cooling time is 60s.

Note that the cooling time is much larger than the time spent for computation. For N = 10000, only 30s are needed for Cholesky factorization at peak performance, but I ask for a 60s cooling time.

This is certainly a very uninteresting setting in high performance computing: we want our machine to work all the time at peak performance, until a very large task is completed. So this kind of halt makes no sense. But it helps to better know the effect of temperature on performance.

This time, we see that peak performance is achieved for all N, just as theory supports! The periodic feature of CPU frequency and temperature is the result of cooling and boost. Temperature still has an increasing trend, simply because as N increases, the work load is getting bigger. This also justifies more cooling time for a sufficient cooling down, as I have done.

The achievement of peak performance seems to rule out all effects other than temperature. But this is really annoying. Basically it says that computer will get tired in HPC, so we can't get expected performance gain. Then what is the point of developing HPC algorithm?

OK, here are the new set of plots:

I don't know why I could not upload the 6th figure. SO simply does not allow me to submit the edit when adding the 6th figure. So I am sorry I can't attach the figure for CPU frequency.

update 2 (how I measure CPU frequency and temperature)

Thanks to Zboson for adding the x86 tag. The following bash commands are what I used for measurement:

while true

do

cat /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq >> cpu0_freq.txt ## parameter "freq0"

cat sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu1/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq >> cpu1_freq.txt ## parameter "freq1"

sensors | grep "Core 0" >> cpu0_temp.txt ## parameter "temp0"

sensors | grep "Core 1" >> cpu1_temp.txt ## parameter "temp1"

sleep 2

done

Since I did not pin the computation to 1 core, the operating system will alternately use two different cores. It makes more sense to take

freq[i] <- max (freq0[i], freq1[i])

temp[i] <- max (temp0[i], temp1[i])

as the overall measurement.

monitor laptop hardware temperatures- e.g. openhardwaremonitor.org, also: cpuid.com/softwares/hwmonitor.html. Search for your specific laptop. imo, I suspect hardware limits as running CPU's flatout for long periods will tax the hardware and it will 'throttle'. It may be worthwhile increasing the priority of the matrix tasks. Please be aware - I really am guessing - you need to do some data collection. – Selfassurancegrep MHz /proc/cpuinfo, but the OP's/sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freqis probably good, if it knows about turbo. If not, your probably need to use.../cpuinfo_cur_freq(which requires root to even read, implying it might be a more expensive operation than reading the scaling governor's current decision. That would make sense if it queries the hardware about turbo, but/proc/cpuinfo's current frequency can be in the turbo range.) – Stringfellow