If you just want the modules, you could just run the code and a new session and go through sys.modules for any module in your package.

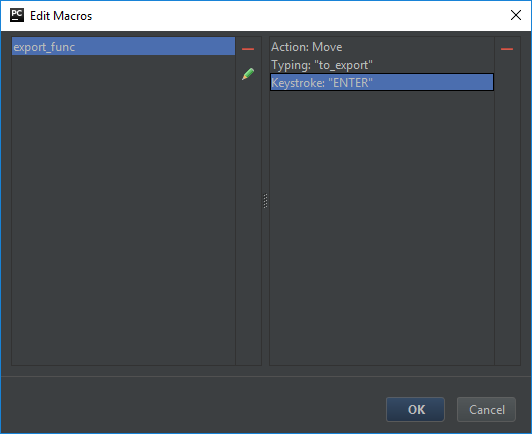

To move all the dependencies with PyCharm, you could make a macro that moves a highlighted object to a predefined file, attach the macro to a keyboard shortcut and then quickly move any in-project imports recursively. For instance, I made a macro called export_func that moves a function to to_export.py and added a shortcut to F10:

![Macro Actions]()

Given a function that I want to move in a file like

from utils import factorize

def my_func():

print(factorize(100))

and utils.py looking something like

import numpy as np

from collections import Counter

import sys

if sys.version_info.major >= 3:

from functools import lru_cache

else:

from functools32 import lru_cache

PREPROC_CAP = int(1e6)

@lru_cache(10)

def get_primes(n):

n = int(n)

sieve = np.ones(n // 3 + (n % 6 == 2), dtype=np.bool)

for i in range(1, int(n ** 0.5) // 3 + 1):

if sieve[i]:

k = 3 * i + 1 | 1

sieve[k * k // 3::2 * k] = False

sieve[k * (k - 2 * (i & 1) + 4) // 3::2 * k] = False

return list(map(int, np.r_[2, 3, ((3 * np.nonzero(sieve)[0][1:] + 1) | 1)]))

@lru_cache(10)

def _get_primes_set(n):

return set(get_primes(n))

@lru_cache(int(1e6))

def factorize(value):

if value == 1:

return Counter()

if value < PREPROC_CAP and value in _get_primes_set(PREPROC_CAP):

return Counter([value])

for p in get_primes(PREPROC_CAP):

if p ** 2 > value:

break

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

for p in range(PREPROC_CAP + 1, int(value ** .5) + 1, 2):

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

return Counter([value])

I can highlight my_func and press F10 to create to_export.py:

from utils import factorize

def my_func():

print(factorize(100))

Highlighting factorize in to_export.py and hitting F10 gets

from collections import Counter

from functools import lru_cache

from utils import PREPROC_CAP, _get_primes_set, get_primes

def my_func():

print(factorize(100))

@lru_cache(int(1e6))

def factorize(value):

if value == 1:

return Counter()

if value < PREPROC_CAP and value in _get_primes_set(PREPROC_CAP):

return Counter([value])

for p in get_primes(PREPROC_CAP):

if p ** 2 > value:

break

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

for p in range(PREPROC_CAP + 1, int(value ** .5) + 1, 2):

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

return Counter([value])

Then highlighting each of PREPROC_CAP, _get_primes_set, and get_primes and

then pressing F10 gets

from collections import Counter

from functools import lru_cache

import numpy as np

def my_func():

print(factorize(100))

@lru_cache(int(1e6))

def factorize(value):

if value == 1:

return Counter()

if value < PREPROC_CAP and value in _get_primes_set(PREPROC_CAP):

return Counter([value])

for p in get_primes(PREPROC_CAP):

if p ** 2 > value:

break

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

for p in range(PREPROC_CAP + 1, int(value ** .5) + 1, 2):

if value % p == 0:

factors = factorize(value // p).copy()

factors[p] += 1

return factors

return Counter([value])

PREPROC_CAP = int(1e6)

@lru_cache(10)

def _get_primes_set(n):

return set(get_primes(n))

@lru_cache(10)

def get_primes(n):

n = int(n)

sieve = np.ones(n // 3 + (n % 6 == 2), dtype=np.bool)

for i in range(1, int(n ** 0.5) // 3 + 1):

if sieve[i]:

k = 3 * i + 1 | 1

sieve[k * k // 3::2 * k] = False

sieve[k * (k - 2 * (i & 1) + 4) // 3::2 * k] = False

return list(map(int, np.r_[2, 3, ((3 * np.nonzero(sieve)[0][1:] + 1) | 1)]))

It goes pretty fast even if you have a lot of code that you're copying over.

from mymodule import func, and you don't use any global variables or duplicate any function names, then you could probably safely gather all the functions into a single script. If you normally useimport mymoduleand thenmymodule.func()then you could have the script create shell versions of each module with just the relevant functions. – Cove