I would like to ensure that the class is only instantiated within a "with" statement.

i.e. this one is ok:

with X() as x:

...

and this is not:

x = X()

How can I ensure such functionality?

I would like to ensure that the class is only instantiated within a "with" statement.

i.e. this one is ok:

with X() as x:

...

and this is not:

x = X()

How can I ensure such functionality?

All answers so far do not provide what (I think) OP wants directly.

(I think) OP wants something like this:

>>> with X() as x:

... # ok

>>> x = X() # ERROR

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "run.py", line 18, in <module>

x = X()

File "run.py", line 9, in __init__

raise Exception("Should only be used with `with`")

Exception: Should only be used with `with`

This is what I come up with, it may not be very robust, but I think it's closest to OP's intention.

import inspect

import linecache

class X():

def __init__(self):

if not linecache.getline(__file__,

inspect.getlineno(inspect.currentframe().f_back)).lstrip(

).startswith("with "):

raise Exception("Should only be used with `with`")

def __enter__(self):

return self

def __exit__(self, *exc_info):

pass

This will give the exact same output as I showed above as long as with is in the same line with X() when using context manager.

with that is at module level –

Bordy .strip() before .startswith("with ") in case it's not top level –

Policlinic while True: with X() as x:. –

Endogamy __enter__ returns. –

Endogamy There is no straight forward way, as far as I know. But, you can have a boolean flag, to check if __enter__ was invoked, before the actual methods in the objects were called.

class MyContextManager(object):

def __init__(self):

self.__is_context_manager = False

def __enter__(self):

print "Entered"

self.__is_context_manager = True

return self

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_value, traceback):

print "Exited"

def do_something(self):

if not self.__is_context_manager:

raise Exception("MyContextManager should be used only with `with`")

print "I don't know what I am doing"

When you use it with with,

with MyContextManager() as y:

y.do_something()

you will get

Entered

I don't know what I am doing

Exited

But, when you manually create an object, and invoke do_something,

x = MyContextManager()

x.do_something()

you will get

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/thefourtheye/Desktop/Test.py", line 22, in <module>

x.do_something()

File "/home/thefourtheye/Desktop/Test.py", line 16, in do_something

raise Exception("MyContextManager should be used only with `with`")

Exception: MyContextManager should be used only with `with`

Note: This is not a solid solution. Somebody can directly invoke __enter__ method alone, before calling any other methods and the __exit__ method may never be called in that case.

If you don't want to repeat that check in every function, you can make it a decorator, like this

class MyContextManager(object):

def __init__(self):

self.__is_context_manager = False

def __enter__(self):

print "Entered"

self.__is_context_manager = True

return self

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_value, traceback):

print "Exited"

def ensure_context_manager(func):

def inner_function(self, *args, **kwargs):

if not self.__is_context_manager:

raise Exception("This object should be used only with `with`")

return func(self, *args, **kwargs)

return inner_function

@ensure_context_manager

def do_something(self):

print "I don't know what I am doing"

__getattribute__ to really nail it down for everything –

Lorelle self from __enter__. Return a different object, and have that object implement do_something(). So MyContextManager() doesn't have a do_something() method at all. The object returned from __enter__ does. –

Wad _Different object" approach is, the latter technically does NOT prevent the caller from initializing the _Different object directly. But I get your point. :-) –

Slippy MyContextManager() instance can be used for multiple contexts if __enter__ produces an independent object. –

Wad .__is_context_manager = True directly either. –

Endogamy There is no foolproof approach to ensure that an instance is constructed within a with clause, but you can create an instance in the __enter__ method and return that instead of self; this is the value that will be assigned into x. Thus you can consider X as a factory that creates the actual instance in its __enter__ method, something like:

class ActualInstanceClass(object):

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

def destroy(self):

print("destroyed")

class X(object):

instance = None

def __enter__(self):

# additionally one can here ensure that the

# __enter__ is not re-entered,

# if self.instance is not None:

# raise Exception("Cannot reenter context manager")

self.instance = ActualInstanceClass(self)

return self.instance

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_value, traceback):

self.instance.destroy()

return None

with X() as x:

# x is now an instance of the ActualInstanceClass

Of course this is still reusable, but every with statement would create a new instance.

Naturally one can call the __enter__ manually, or get a reference to the ActualInstanceClass but it would be more of abuse instead of use.

For an even smellier approach, the X() when called does actually create a XFactory instance, instead of an X instance; and this in turn when used as a context manager, creates the ActualX instance which is the subclass of X, thus isinstance(x, X) will return true.

class XFactory(object):

managed = None

def __enter__(self):

if self.managed:

raise Exception("Factory reuse not allowed")

self.managed = ActualX()

return self.managed

def __exit__(self, *exc_info):

self.managed.destroy()

return

class X(object):

def __new__(cls):

if cls == X:

return XFactory()

return super(X, cls).__new__(cls)

def do_foo(self):

print("foo")

def destroy(self):

print("destroyed")

class ActualX(X):

pass

with X() as x:

print(isinstance(x, X)) # yes it is an X instance

x.do_foo() # it can do foo

# x is destroyed

newx = X()

newx.do_foo() # but this can't,

# AttributeError: 'XFactory' object has no attribute 'do_foo'

You could take this further and have XFactory create an actual X instance with a special keyword argument to __new__, but I consider it to be too black magic to be useful.

__enter__, so you can produce a new, special object to use in the context you just entered. That's what many database connections do, for example: return a transaction or cursor for a context. –

Wad __enter__ is for. –

Wad All answers so far do not provide what (I think) OP wants directly.

(I think) OP wants something like this:

>>> with X() as x:

... # ok

>>> x = X() # ERROR

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "run.py", line 18, in <module>

x = X()

File "run.py", line 9, in __init__

raise Exception("Should only be used with `with`")

Exception: Should only be used with `with`

This is what I come up with, it may not be very robust, but I think it's closest to OP's intention.

import inspect

import linecache

class X():

def __init__(self):

if not linecache.getline(__file__,

inspect.getlineno(inspect.currentframe().f_back)).lstrip(

).startswith("with "):

raise Exception("Should only be used with `with`")

def __enter__(self):

return self

def __exit__(self, *exc_info):

pass

This will give the exact same output as I showed above as long as with is in the same line with X() when using context manager.

with that is at module level –

Bordy .strip() before .startswith("with ") in case it's not top level –

Policlinic while True: with X() as x:. –

Endogamy __enter__ returns. –

Endogamy Unfortunately, you can't very cleanly.

Context managers require having __enter__ and __exit__ methods, so you can use this to assign a member variable on the class to check in your code.

class Door(object):

def __init__(self, state='closed'):

self.state = state

self.called_with_open = False

# When being called as a non-context manger object,

# __enter__ and __exit__ are not called.

def __enter__(self):

self.called_with_open = True

self.state = 'opened'

def __exit__(self, type, value, traceback):

self.state = 'closed'

def was_context(self):

return self.called_with_open

if __name__ == '__main__':

d = Door()

if d.was_context():

print("We were born as a contextlib object.")

with Door() as d:

print('Knock knock.')

The stateful object approach has the nice added benefit of being able to tell if the __exit__ method was called later, or to cleanly handle method requirements in later calls:

def walk_through(self):

if self.state == 'closed':

self.__enter__

walk()

__enter__. –

Wad OP's question was believed to be an XY problem, and the current chosen answer was indeed (too?) hacky.

I don't really know the OP's original "X problem", but I'd assume the motivation was NOT literally about to "prevent x = X() ASSIGNMENT from working". Instead, it could be about to force the API user to always use x as a context manager, so that its __exit__(...) would always be triggered, which is the whole point of designing class X to be a context manager in the first place. At least, that was the reason brought me to this Q&A post.

class Holder(object):

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self._data = allocate(...) # Say, it allocates 1 GB of memory, or a long-lived connection, etc.

def do_something(self):

do_something_with(self._data)

def tear_down(self):

unallocate(self._data)

def __enter__(self):

return self

def __exit__(self, *args):

self.tear_down()

# This is desirable

with Holder(...) as holder:

holder.do_something()

# This might not free the resource immediately, if at all

def foo():

holder = Holder(...)

holder.do_something()

That said, after learning all the conversations here, I ended up just leave my Holder class as-is, well, I just added one more docstring for my tear_down():

def tear_down(self):

"""You are expect to call this eventually; or you can simply use this class as a context manager."""

...

After all, we are all consenting adults here...

Here is a decorator that automates making sure methods aren't called outside of a context manager:

from functools import wraps

BLACKLIST = dir(object) + ['__enter__']

def context_manager_only(cls):

original_init = cls.__init__

def init(self, *args, **kwargs):

original_init(self, *args, **kwargs)

self._entered = False

cls.__init__ = init

original_enter = cls.__enter__

def enter(self):

self._entered = True

return original_enter(self)

cls.__enter__ = enter

attrs = {name: getattr(cls, name) for name in dir(cls) if name not in BLACKLIST}

methods = {name: method for name, method in attrs.items() if callable(method)}

for name, method in methods.items():

def make_wrapper(method=method):

@wraps(method)

def wrapper_method(self, *args, **kwargs):

if not self._entered:

raise Exception("Didn't get call to __enter__")

return method(self, *args, **kwargs)

return wrapper_method

setattr(cls, name, make_wrapper())

return cls

And here is an example of it in use:

@context_manager_only

class Foo(object):

def func1(self):

print "func1"

def func2(self):

print "func2"

def __enter__(self):

print "enter"

return self

def __exit__(self, *args):

print "exit"

try:

print "trying func1:"

Foo().func1()

except Exception as e:

print e

print "trying enter:"

with Foo() as foo:

print "trying func1:"

foo.func1()

print "trying func2:"

foo.func2()

print "trying exit:"

This was written as an answer to this duplicate question.

__enter__ instead of self, and that object implements the methods you want to expose in the context. –

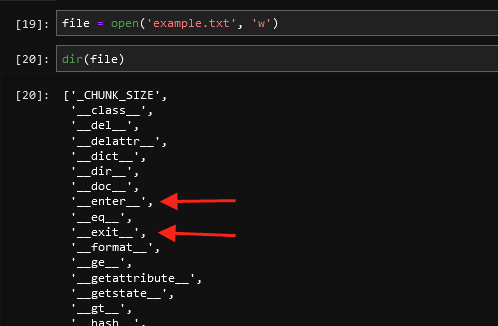

Wad There is a way. You can call dir() function to see all properties and methods.

Context manager needs __enter__ and __exit__ implemented to work accordingly documentation: https://docs.python.org/3/library/contextlib.html

© 2022 - 2025 — McMap. All rights reserved.

x = X(),with x as result_of_entering:(creating the CM and using it on two separate lines) is a valid use-case! What if I wanted to store CMs in a mapping to select one dynamically, or use ancontextlib.ExitStack()? to combine multiple CMs? There are numerous use-cases where a CM is created outside of awithstatement that you would block. Don't try and fix all possible errors at the expense of making it harder for those that know what they are doing. – Wadx = X()from working? Can you tell me why you think that that is needed? Python doesn’t see assignment of objects as anything that needs to be prevented or special. TheX()call expression inx = X()andwith X() as x:is treated exactly the same by Python, both put the result on the stack so the next instruction (the assignment or with statement block setup) can work with that object. Preventing assignment doesn’t make sense here and would actively break important use-cases. – Wad__enter__, so the thing that's assigned totargetin the following three linesx = X()/with x as target:/# do stuff with target. Thenx = X()is 'harmless', as that's not the same type of object astarget. – Wad