Why would you want to turn it off for release builds? – dan-gph

I have seen too many Delphi programmers writing quite large programs without ever activating Range, Overflow and Assertion checking. Of course, you can do that if you want, but your code will be more buggy.

I hope to convince more programmers to enable these 3 checking right now, to make the program more reliable.

However, note that there is a price to pay for that: your program will be slower. I show below some actual time comparison of code running with and without range checking.

the point is you can turn it off locally where you need to with {$R-}.But you can leave it on globally in the project settings –

dan-gph

Personally, next to Debug and Release, I have a 3rd option called PreRelease. This is actually a Debug version with one single setting different: the "Optimizations" is on. It is fast enough while it still does the checking (range, overflow, assertions, etc).

I release this kind of version to a limited number (~1000) of customers. If all seems good after one week, I swap it with the true Release version, where the checkings are off.

Overflow checking

This will check certain integer arithmetic operations (+, -, *, Abs, Sqr, Succ, Pred, Inc, and Dec) for overflow. For example, after a + (addition) operation the compiler will insert additional binary code that verifies that the result of the operation is within the supported range.

An "integer overflow" occurs when an operation on an integer variable produces a result that is outside the range of that variable. For example, if an integer variable is declared as a 16-bit signed integer, its value can range from -32768 to 32767. If an operation on this variable produces a result greater than 32767 or less than -32768, an integer overflow has occurred.

When an integer overflow occurs, the result of the operation is undefined and can lead to undefined behavior in the program:

• Wrap-around

The result might result in a wrapped-around value. This means that the number 32768 will be actually stored as 1 since it is 1 unit higher than the highest value we can store (32767).

• Truncation

The result may be truncated or otherwise modified to fit within the range of the integer type. For example, the number 32768 will be actually stored as 32767 since that is the highest value we can store.

Undefined program behavior is one of the worst kind of errors, because it is not an error easy to reproduce. Therefore, it is difficult to track and repair.

There is a small price to pay if you activate this: the speed of the program will decrease slightly.

IO checking

Checks the result of an I/O operation. If an I/O operation fails, an exception is raised. If this switch is off, we must check for I/O errors manually.

There is a minor price to pay if you activate this: the speed of the program will decrease, but insignificantly because the few microseconds introduced by this check is nothing compared with the millisecond-range time required by the I/O operation itself (the hard drives are slow).

Range Checking

The Delphi Geek calls this “The most important Delphi setting” and I totally agree. It checks if all array and string indexing expressions are within the defined bounds. It also checks that all assignments to scalar and subrange variables are within range.

Here is an example of code that would ruin our life if Range Checking would not be available:

Type

Pasword= array [1..10] of byte; // we define an array of 10 elements

…

x:= Pasword[20]; // Range Checking will prevent the program from accessing element 20 (ERangecheckError exception is raised). Security breach avoided. Error log automatically sent to the programmer. Bruce Willis saves everyone.

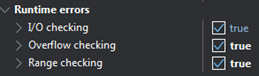

Enabling Runtime Error Checking

To activate the Runtime Error Checking, go to Project Options and check these three boxes:

Enabling the Runtime Error Checking in ‘Project Options’

![enter image description here]()

Assertions

A good programmer MUST use assertions in its code to increase the quality and stability of the program. Seriously man! You really need to use them.

Assertions are used to check for conditions that should always be true at a certain point in the program, and to raise an exception if the condition is not met. The Assert procedure, which is defined in the SysUtils unit, is typically used to perform assertions.

You can think of assertions as poor man’s unit testing. I strongly advise you to look deeper into assertions. They are very useful and do not require as much work as unit testing.

Typical example:

SysUtils.Assert(Input <> Nil, ‘The input should not be nil!’);

But for the program to check our assertions, we need to active this feature in the Project Settings -> Compiler Options, otherwise they will simply be ignored, like they are not there in our code. Make sure that you understand the implications of what I just said! For example, we screw up badly if we call routines that have side effects in the Assert. In the example below, during Debugging when the assertions are on, the Test() function will be executed and 'This was executed' will appear in the Memo. However, during Release more, that text will not appear in the memo because now Assert is simply ignored. Congratulations we just made the program to behave differently in debug/release mode ☹.

function TMainForm.Test: Boolean;

begin

Result:= FALSE;

mmo.Lines.Add('This was executed');

end;

procedure TMainForm.Start;

VAR x: Integer;

begin

x:= 0;

if x= 0

then Assert(Test(), 'nope');

end;

Here are a few examples of how it can be used:

1 To check if an input parameter is within the 0..100 range:

procedure DoSomething(value: Integer);

begin

Assert((value >= 0) and (value <= 100), 'Value out of range');

…

end;

2 To check if a pointer is not nil before using it:

Var p: Pointer;

Begin

p := GetPointer;

Assert(Assigned(p), 'Pointer is nil');

…

End;

3 To check if a variable has a certain value before proceeding:

var i: Integer;

begin

i := GetValue;

Assert(i = 42, 'Incorrect response to “What is the answer to life”!');

…

end;

Assertions can also be disabled by defining the NDEBUG symbol in the project options or by using the {$D-} compiler directives.

We can also use the Assert as a more elegant way of handling errors and exceptions in some cases, as it can be more readable and it also includes a custom message, that would help the developer understand what went wrong.

Personally, I use it a lot at the top of my routines to check if the parameters are valid.

Activating this feature will (naturally) make your program slower because… well, there is one extra line of code to execute.

Nothing comes for free

Everything nice comes with a price (fortunately a small price in our case): enabling Runtime error checking and Assertions slows down our program and makes it somewhat larger.

Computers today have lots of RAM so the slight increase in size is irrelevant, so, let’s put that aside. But let’s look at the speed, because that is not something we can easily ignore:

Type Disabled Enabled

Range checking 73ms 120ms

Overflow checking 580ms 680ms

I/O checking Not tested Not tested

As we can see the program's speed is strongly impacted by these runtime checking. If we have a program where speed is critical, we better activate “Runtime error checking” during debugging only. What I do, I also leave it active in the first release and wait a few weeks. If no bugs are reported, then I release an update in which “Runtime error checking” is off.

Personally, I leave the “IO checking” always active. The performance hit because of this check is microscopic.

Big warning:

If you have an existing project that was not so nicely written, and you activate any of the Runtime Error checking below, your program may will crash more often than usual.

No, the Runtime Error checking routines did not break your program. It was always broken – you just didn’t know. The Runtime Checking routines are now finding all those places where the code is fishy and shitty and smelly. The sole purpose of Runtime Checking is to find bugs in your program.