(This answer took a while to write, and codeWizard's answer is correct in aim and essence, but not entirely complete, so I'll post this anyway.)

There is no such thing as a "remote Git tag". There are only "tags". I point all this out not to be pedantic,1 but because there is a great deal of confusion about this with casual Git users, and the Git documentation is not very helpful2 to beginners. (It's not clear if the confusion comes because of poor documentation, or the poor documentation comes because this is inherently somewhat confusing, or what.)

There are "remote branches", more properly called "remote-tracking branches", but it's worth noting that these are actually local entities. There are no remote tags, though (unless you (re)invent them). There are only local tags, so you need to get the tag locally in order to use it.

The general form for names for specific commits—which Git calls references—is any string starting with refs/. A string that starts with refs/heads/ names a branch; a string starting with refs/remotes/ names a remote-tracking branch; and a string starting with refs/tags/ names a tag. The name refs/stash is the stash reference (as used by git stash; note the lack of a trailing slash).

There are some unusual special-case names that do not begin with refs/: HEAD, ORIG_HEAD, MERGE_HEAD, and CHERRY_PICK_HEAD in particular are all also names that may refer to specific commits (though HEAD normally contains the name of a branch, i.e., contains ref: refs/heads/branch). But in general, references start with refs/.

One thing Git does to make this confusing is that it allows you to omit the refs/, and often the word after refs/. For instance, you can omit refs/heads/ or refs/tags/ when referring to a local branch or tag—and in fact you must omit refs/heads/ when checking out a local branch! You can do this whenever the result is unambiguous, or—as we just noted—when you must do it (for git checkout branch).

It's true that references exist not only in your own repository, but also in remote repositories. However, Git gives you access to a remote repository's references only at very specific times: namely, during fetch and push operations. You can also use git ls-remote or git remote show to see them, but fetch and push are the more interesting points of contact.

Refspecs

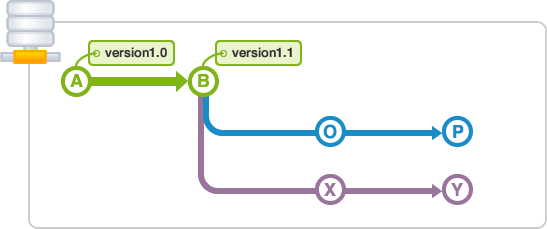

During fetch and push, Git uses strings it calls refspecs to transfer references between the local and remote repository. Thus, it is at these times, and via refspecs, that two Git repositories can get into sync with each other. Once your names are in sync, you can use the same name that someone with the remote uses. There is some special magic here on fetch, though, and it affects both branch names and tag names.

You should think of git fetch as directing your Git to call up (or perhaps text-message) another Git—the "remote"—and have a conversation with it. Early in this conversation, the remote lists all of its references: everything in refs/heads/ and everything in refs/tags/, along with any other references it has. Your Git scans through these and (based on the usual fetch refspec) renames their branches.

Let's take a look at the normal refspec for the remote named origin:

$ git config --get-all remote.origin.fetch

+refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

$

This refspec instructs your Git to take every name matching refs/heads/*—i.e., every branch on the remote—and change its name to refs/remotes/origin/*, i.e., keep the matched part the same, changing the branch name (refs/heads/) to a remote-tracking branch name (refs/remotes/, specifically, refs/remotes/origin/).

It is through this refspec that origin's branches become your remote-tracking branches for remote origin. Branch name becomes remote-tracking branch name, with the name of the remote, in this case origin, included. The plus sign + at the front of the refspec sets the "force" flag, i.e., your remote-tracking branch will be updated to match the remote's branch name, regardless of what it takes to make it match. (Without the +, branch updates are limited to "fast forward" changes, and tag updates are simply ignored since Git version 1.8.2 or so—before then the same fast-forward rules applied.)

Tags

But what about tags? There's no refspec for them—at least, not by default. You can set one, in which case the form of the refspec is up to you; or you can run git fetch --tags. Using --tags has the effect of adding refs/tags/*:refs/tags/* to the refspec, i.e., it brings over all tags (but does not update your tag if you already have a tag with that name, regardless of what the remote's tag says Edit, Jan 2017: as of Git 2.10, testing shows that --tags forcibly updates your tags from the remote's tags, as if the refspec read +refs/tags/*:refs/tags/*; this may be a difference in behavior from an earlier version of Git).

Note that there is no renaming here: if remote origin has tag xyzzy, and you don't, and you git fetch origin "refs/tags/*:refs/tags/*", you get refs/tags/xyzzy added to your repository (pointing to the same commit as on the remote). If you use +refs/tags/*:refs/tags/* then your tag xyzzy, if you have one, is replaced by the one from origin. That is, the + force flag on a refspec means "replace my reference's value with the one my Git gets from their Git".

Automagic tags during fetch

For historical reasons,3 if you use neither the --tags option nor the --no-tags option, git fetch takes special action. Remember that we said above that the remote starts by displaying to your local Git all of its references, whether your local Git wants to see them or not.4 Your Git takes note of all the tags it sees at this point. Then, as it begins downloading any commit objects it needs to handle whatever it's fetching, if one of those commits has the same ID as any of those tags, git will add that tag—or those tags, if multiple tags have that ID—to your repository.

Edit, Jan 2017: testing shows that the behavior in Git 2.10 is now: If their Git provides a tag named T, and you do not have a tag named T, and the commit ID associated with T is an ancestor of one of their branches that your git fetch is examining, your Git adds T to your tags with or without --tags. Adding --tags causes your Git to obtain all their tags, and also force update.

Bottom line

You may have to use git fetch --tags to get their tags. If their tag names conflict with your existing tag names, you may (depending on Git version) even have to delete (or rename) some of your tags, and then run git fetch --tags, to get their tags. Since tags—unlike remote branches—do not have automatic renaming, your tag names must match their tag names, which is why you can have issues with conflicts.

In most normal cases, though, a simple git fetch will do the job, bringing over their commits and their matching tags, and since they—whoever they are—will tag commits at the time they publish those commits, you will keep up with their tags. If you don't make your own tags, nor mix their repository and other repositories (via multiple remotes), you won't have any tag name collisions either, so you won't have to fuss with deleting or renaming tags in order to obtain their tags.

When you need qualified names

I mentioned above that you can omit refs/ almost always, and refs/heads/ and refs/tags/ and so on most of the time. But when can't you?

The complete (or near-complete anyway) answer is in the gitrevisions documentation. Git will resolve a name to a commit ID using the six-step sequence given in the link. Curiously, tags override branches: if there is a tag xyzzy and a branch xyzzy, and they point to different commits, then:

git rev-parse xyzzy

will give you the ID to which the tag points. However—and this is what's missing from gitrevisions—git checkout prefers branch names, so git checkout xyzzy will put you on the branch, disregarding the tag.

In case of ambiguity, you can almost always spell out the ref name using its full name, refs/heads/xyzzy or refs/tags/xyzzy. (Note that this does work with git checkout, but in a perhaps unexpected manner: git checkout refs/heads/xyzzy causes a detached-HEAD checkout rather than a branch checkout. This is why you just have to note that git checkout will use the short name as a branch name first: that's how you check out the branch xyzzy even if the tag xyzzy exists. If you want to check out the tag, you can use refs/tags/xyzzy.)

Because (as gitrevisions notes) Git will try refs/name, you can also simply write tags/xyzzy to identify the commit tagged xyzzy. (If someone has managed to write a valid reference named xyzzy into $GIT_DIR, however, this will resolve as $GIT_DIR/xyzzy. But normally only the various *HEAD names should be in $GIT_DIR.)

1Okay, okay, "not just to be pedantic". :-)

2Some would say "very not-helpful", and I would tend to agree, actually.

3Basically, git fetch, and the whole concept of remotes and refspecs, was a bit of a late addition to Git, happening around the time of Git 1.5. Before then there were just some ad-hoc special cases, and tag-fetching was one of them, so it got grandfathered in via special code.

4If it helps, think of the remote Git as a flasher, in the slang meaning.