Case k = 2: np.triu_indices

I've tested case k = 2 using lots of variations of abovementioned functions using perfplot. The winner is, no doubt, np.triu_indices and I see now that using np.dtype([('', np.intp)] * 2) data structure can be a huge boost even for exotic data types such as igraph.EdgeList.

from itertools import combinations, chain

from scipy.special import comb

import igraph as ig #graph library build on C

import networkx as nx #graph library, pure Python

def _combs(n):

return np.array(list(combinations(range(n),2)))

def _combs_fromiter(n): #@Jaime

indices = np.arange(n)

dt = np.dtype([('', np.intp)]*2)

indices = np.fromiter(combinations(indices, 2), dt)

indices = indices.view(np.intp).reshape(-1, 2)

return indices

def _combs_fromiterplus(n):

dt = np.dtype([('', np.intp)]*2)

indices = np.fromiter(combinations(range(n), 2), dt)

indices = indices.view(np.intp).reshape(-1, 2)

return indices

def _numpy(n): #@endolith

return np.transpose(np.triu_indices(n,1))

def _igraph(n):

return np.array(ig.Graph(n).complementer(False).get_edgelist())

def _igraph_fromiter(n):

dt = np.dtype([('', np.intp)]*2)

indices = np.fromiter(ig.Graph(n).complementer(False).get_edgelist(), dt)

indices = indices.view(np.intp).reshape(-1, 2)

return indices

def _nx(n):

G = nx.Graph()

G.add_nodes_from(range(n))

return np.array(list(nx.complement(G).edges))

def _nx_fromiter(n):

G = nx.Graph()

G.add_nodes_from(range(n))

dt = np.dtype([('', np.intp)]*2)

indices = np.fromiter(nx.complement(G).edges, dt)

indices = indices.view(np.intp).reshape(-1, 2)

return indices

def _comb_index(n): #@HYRY

count = comb(n, 2, exact=True)

index = np.fromiter(chain.from_iterable(combinations(range(n), 2)),

int, count=count*2)

return index.reshape(-1, 2)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

plt.grid(True, which="both")

out = perfplot.bench(

setup = lambda x: x,

kernels = [_numpy, _combs, _combs_fromiter, _combs_fromiterplus,

_comb_index, _igraph, _igraph_fromiter, _nx, _nx_fromiter],

n_range = [2 ** k for k in range(12)],

xlabel = 'combinations(n, 2)',

title = 'testing combinations',

show_progress = False,

equality_check = False)

out.show()

![enter image description here]()

Wondering why np.triu_indices can't be extended to more dimensions?

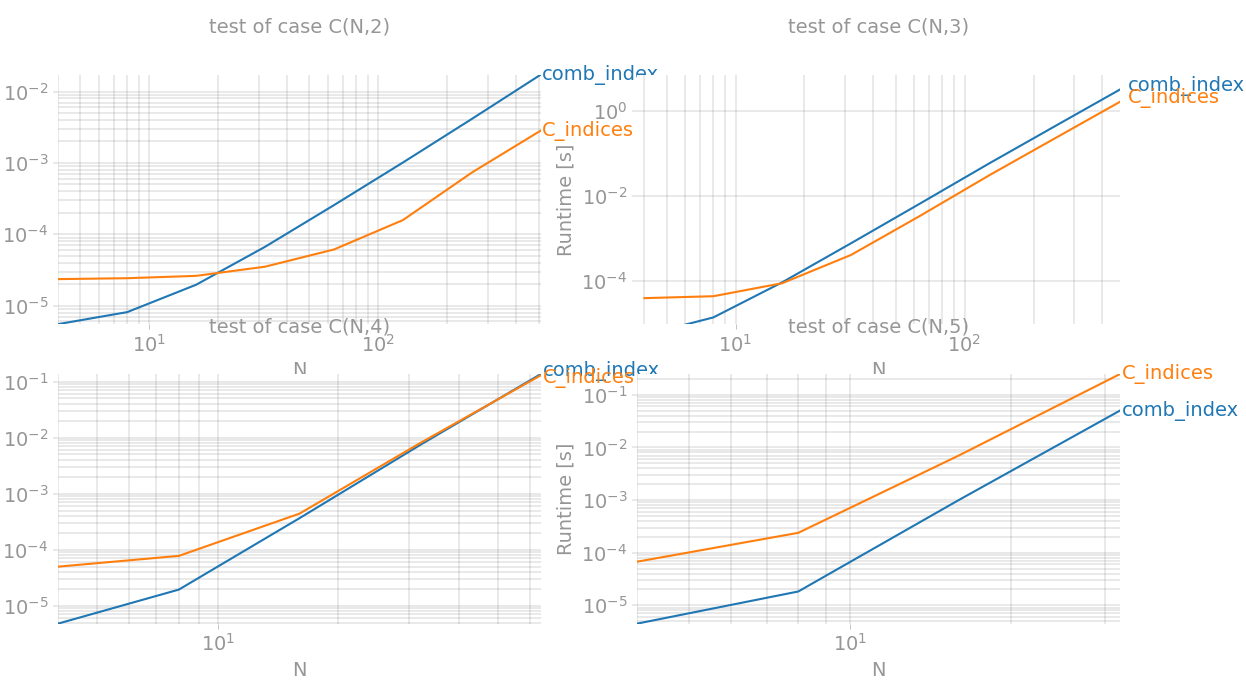

Case 2 ≤ k ≤ 4: triu_indices(implemented here) = up to 2x speedup

np.triu_indices could actually be a winner for case k = 3 and even k = 4 if we implement a generalised method instead. A current version of this method is equivalent of:

def triu_indices(n, k):

x = np.less.outer(np.arange(n), np.arange(-k+1, n-k+1))

return np.nonzero(x)

It constructs matrix representation of a relation x < y for two sequences 0,1,...,n-1 and finds locations of cells where they are not zero. For 3D case we need to add extra dimension and intersect relations x < y and y < z. For next dimensions procedure is the same but this gets a huge memory overload since n^k binary cells are needed and only C(n, k) of them attains True values. Memory usage and performance grows by O(n!) so this algorithm outperformans itertools.combinations only for small values of k. This is best to use actually for case k=2 and k=3

def C(n, k): #huge memory overload...

if k==0:

return np.array([])

if k==1:

return np.arange(1,n+1)

elif k==2:

return np.less.outer(np.arange(n), np.arange(n))

else:

x = C(n, k-1)

X = np.repeat(x[None, :, :], len(x), axis=0)

Y = np.repeat(x[:, :, None], len(x), axis=2)

return X&Y

def C_indices(n, k):

return np.transpose(np.nonzero(C(n,k)))

Let's checkout with perfplot:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import perfplot

from itertools import chain, combinations

from scipy.special import comb

def C(n, k): # huge memory overload...

if k == 0:

return np.array([])

if k == 1:

return np.arange(1, n + 1)

elif k == 2:

return np.less.outer(np.arange(n), np.arange(n))

else:

x = C(n, k - 1)

X = np.repeat(x[None, :, :], len(x), axis=0)

Y = np.repeat(x[:, :, None], len(x), axis=2)

return X & Y

def C_indices(data):

n, k = data

return np.transpose(np.nonzero(C(n, k)))

def comb_index(data):

n, k = data

count = comb(n, k, exact=True)

index = np.fromiter(chain.from_iterable(combinations(range(n), k)),

int, count=count * k)

return index.reshape(-1, k)

def build_args(k):

return {'setup': lambda x: (x, k),

'kernels': [comb_index, C_indices],

'n_range': [2 ** x for x in range(2, {2: 10, 3:10, 4:7, 5:6}[k])],

'xlabel': f'N',

'title': f'test of case C(N,{k})',

'show_progress': True,

'equality_check': lambda x, y: np.array_equal(x, y)}

outs = [perfplot.bench(**build_args(n)) for n in (2, 3, 4, 5)]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(20, 20))

for i in range(len(outs)):

ax = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, i + 1)

ax.grid(True, which="both")

outs[i].plot()

plt.show()

![enter image description here]()

So the best performance boost is achieved for k=2 (equivalent to np.triu_indices) and for k=3` it's faster almost twice.

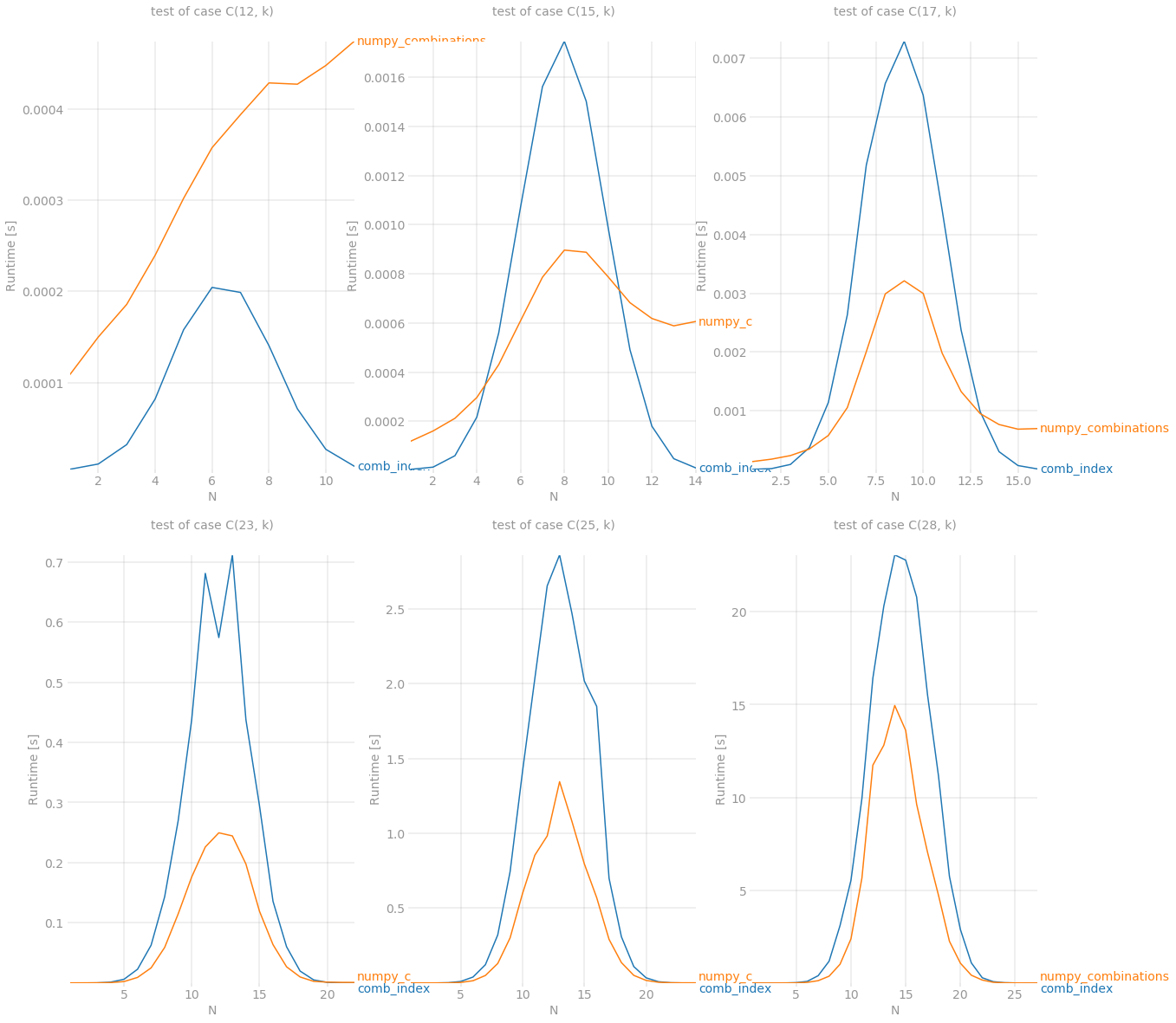

Case k > 3: numpy_combinations(implemented here) = up to 2.5x speedup

Following this question (thanks @Divakar) I managed to find a way to calculate values of specific column based on previous column and Pascal's triangle. It's not optimized yet as much as it could but results are really promising. Here we go:

from scipy.linalg import pascal

def stretch(a, k):

l = a.sum()+len(a)*(-k)

out = np.full(l, -1, dtype=int)

out[0] = a[0]-1

idx = (a-k).cumsum()[:-1]

out[idx] = a[1:]-1-k

return out.cumsum()

def numpy_combinations(n, k):

#n, k = data #benchmark version

n, k = data

x = np.array([n])

P = pascal(n).astype(int)

C = []

for b in range(k-1,-1,-1):

x = stretch(x, b)

r = P[b][x - b]

C.append(np.repeat(x, r))

return n - 1 - np.array(C).T

And the benchmark results are:

# script is the same as in previous example except this part

def build_args(k):

return {'setup': lambda x: (k, x),

'kernels': [comb_index, numpy_combinations],

'n_range': [x for x in range(1, k)],

'xlabel': f'N',

'title': f'test of case C({k}, k)',

'show_progress': True,

'equality_check': False}

outs = [perfplot.bench(**build_args(n)) for n in (12, 15, 17, 23, 25, 28)]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(20, 20))

for i in range(len(outs)):

ax = fig.add_subplot(2, 3, i + 1)

ax.grid(True, which="both")

outs[i].plot()

plt.show()

![enter image description here]()

Despite it still can't fight with itertools.combinations for n < 15 but it is a new winner in other cases. Last but not least, numpy demonstrates its power when amount of combinations gets reaaallly big. It was able to survive while processing C(28, 14) combinations which is around 40'000'000 items of size 14

numpy_combinationsis limited in taking combinations n=35, k=3 – Draconian