Double dispatch is just one reason among others to use this pattern.

But note that it is the single way to implement double or more dispatch in languages that uses a single dispatch paradigm.

Here are reasons to use the pattern :

1) We want to define new operations without changing the model at each time because the model doesn’t change often wile operations change frequently.

2) We don't want to couple model and behavior because we want to have a reusable model in multiple applications or we want to have an extensible model that allow client classes to define their behaviors with their own classes.

3) We have common operations that depend on the concrete type of the model but we don’t want to implement the logic in each subclass as that would explode common logic in multiple classes and so in multiple places.

4) We are using a domain model design and model classes of the same hierarchy perform too many distinct things that could be gathered somewhere else.

5) We need a double dispatch.

We have variables declared with interface types and we want to be able to process them according their runtime type … of course without using if (myObj instanceof Foo) {} or any trick.

The idea is for example to pass these variables to methods that declares a concrete type of the interface as parameter to apply a specific processing.

This way of doing is not possible out of the box with languages relies on a single-dispatch because the chosen invoked at runtime depends only on the runtime type of the receiver.

Note that in Java, the method (signature) to call is chosen at compile time and it depends on the declared type of the parameters, not their runtime type.

The last point that is a reason to use the visitor is also a consequence because as you implement the visitor (of course for languages that doesn’t support multiple dispatch), you necessarily need to introduce a double dispatch implementation.

Note that the traversal of elements (iteration) to apply the visitor on each one is not a reason to use the pattern.

You use the pattern because you split model and processing.

And by using the pattern, you benefit in addition from an iterator ability.

This ability is very powerful and goes beyond iteration on common type with a specific method as accept() is a generic method.

It is a special use case. So I will put that to one side.

Example in Java

I will illustrate the added value of the pattern with a chess example where we would like to define processing as player requests a piece moving.

Without the visitor pattern use, we could define piece moving behaviors directly in the pieces subclasses.

We could have for example a Piece interface such as :

public interface Piece{

boolean checkMoveValidity(Coordinates coord);

void performMove(Coordinates coord);

Piece computeIfKingCheck();

}

Each Piece subclass would implement it such as :

public class Pawn implements Piece{

@Override

public boolean checkMoveValidity(Coordinates coord) {

...

}

@Override

public void performMove(Coordinates coord) {

...

}

@Override

public Piece computeIfKingCheck() {

...

}

}

And the same thing for all Piece subclasses.

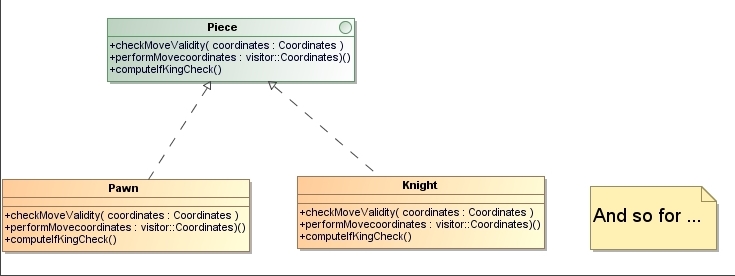

Here is a diagram class that illustrates this design :

![[model class diagram]()

This approach presents three important drawbacks :

– behaviors such as performMove() or computeIfKingCheck() will very probably use common logic.

For example whatever the concrete Piece, performMove() will finally set the current piece to a specific location and potentially takes the opponent piece.

Splitting related behaviors in multiple classes instead of gathering them defeats in a some way the single responsibility pattern. Making their maintainability harder.

– processing as checkMoveValidity() should not be something that the Piece subclasses may see or change.

It is check that goes beyond human or computer actions. This check is performed at each action requested by a player to ensure that the requested piece move is valid.

So we even don’t want to provide that in the Piece interface.

– In chess games challenging for bot developers, generally the application provides a standard API (Piece interfaces, subclasses, Board, common behaviors, etc…) and let developers enrich their bot strategy.

To be able to do that, we have to propose a model where data and behaviors are not tightly coupled in the Piece implementations.

So let’s go to use the visitor pattern !

We have two kinds of structure :

– the model classes that accept to be visited (the pieces)

– the visitors that visit them (moving operations)

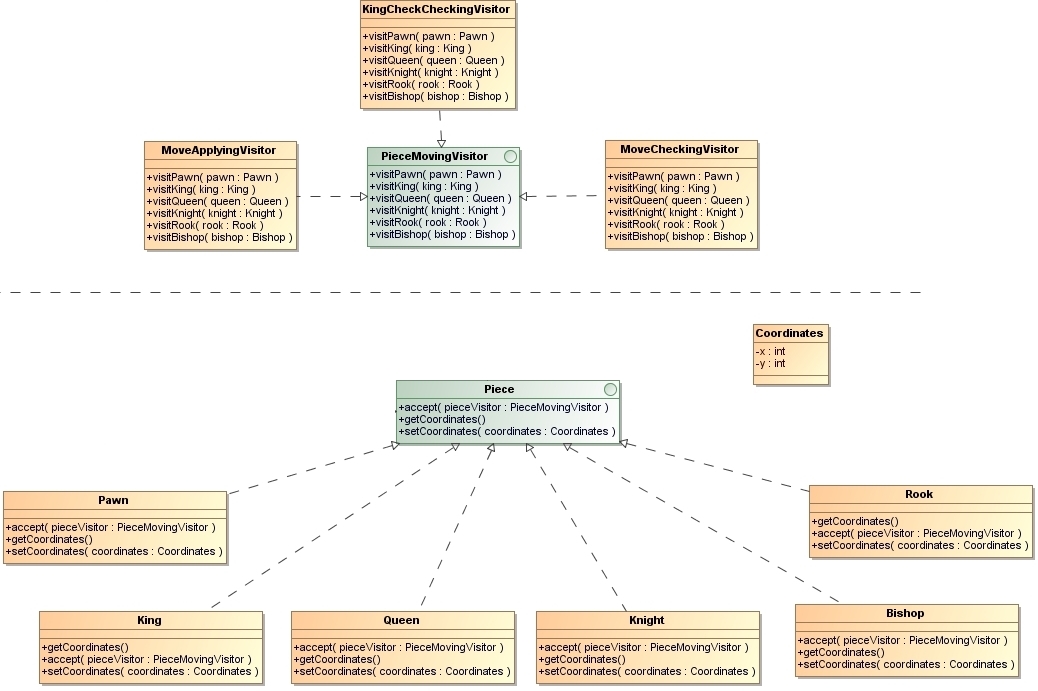

Here is a class diagram that illustrates the pattern :

![enter image description here]()

In the upper part we have the visitors and in the lower part we have the model classes.

Here is the PieceMovingVisitor interface (behavior specified for each kind of Piece) :

public interface PieceMovingVisitor {

void visitPawn(Pawn pawn);

void visitKing(King king);

void visitQueen(Queen queen);

void visitKnight(Knight knight);

void visitRook(Rook rook);

void visitBishop(Bishop bishop);

}

The Piece is defined now :

public interface Piece {

void accept(PieceMovingVisitor pieceVisitor);

Coordinates getCoordinates();

void setCoordinates(Coordinates coordinates);

}

Its key method is :

void accept(PieceMovingVisitor pieceVisitor);

It provides the first dispatch : a invocation based on the Piece receiver.

At compile time, the method is bound to the accept() method of the Piece interface and at runtime, the bounded method will be invoked on the runtime Piece class.

And it is the accept() method implementation that will perform a second dispatch.

Indeed, each Piece subclass that wants to be visited by a PieceMovingVisitor object invokes the PieceMovingVisitor.visit() method by passing as argument itself.

In this way, the compiler bounds as soon as the compile time, the type of the declared parameter with the concrete type.

There is the second dispatch.

Here is the Bishop subclass that illustrates that :

public class Bishop implements Piece {

private Coordinates coord;

public Bishop(Coordinates coord) {

super(coord);

}

@Override

public void accept(PieceMovingVisitor pieceVisitor) {

pieceVisitor.visitBishop(this);

}

@Override

public Coordinates getCoordinates() {

return coordinates;

}

@Override

public void setCoordinates(Coordinates coordinates) {

this.coordinates = coordinates;

}

}

And here an usage example :

// 1. Player requests a move for a specific piece

Piece piece = selectPiece();

Coordinates coord = selectCoordinates();

// 2. We check with MoveCheckingVisitor that the request is valid

final MoveCheckingVisitor moveCheckingVisitor = new MoveCheckingVisitor(coord);

piece.accept(moveCheckingVisitor);

// 3. If the move is valid, MovePerformingVisitor performs the move

if (moveCheckingVisitor.isValid()) {

piece.accept(new MovePerformingVisitor(coord));

}

Visitor drawbacks

The Visitor pattern is a very powerful pattern but it also has some important limitations that you should consider before using it.

1) Risk to reduce/break the encapsulation

In some kinds of operation, the visitor pattern may reduce or break the encapsulation of domain objects.

For example, as the MovePerformingVisitor class needs to set the coordinates of the actual piece, the Piece interface has to provide a way to do that :

void setCoordinates(Coordinates coordinates);

The responsibility of Piece coordinates changes is now open to other classes than Piece subclasses.

Moving the processing performed by the visitor in the Piece subclasses is not an option either.

It will indeed create another issue as the Piece.accept() accepts any visitor implementation. It doesn't know what the visitor performs and so no idea about whether and how to change the Piece state.

A way to identify the visitor would be to perform a post processing in Piece.accept() according to the visitor implementation. It would be a very bad idea as it would create a high coupling between Visitor implementations and Piece subclasses and besides it would probably require to use trick as getClass(), instanceof or any marker identifying the Visitor implementation.

2) Requirement to change the model

Contrary to some other behavioral design patterns as Decorator for example, the visitor pattern is intrusive.

We indeed need to modify the initial receiver class to provide an accept() method to accept to be visited.

We didn't have any issue for Piece and its subclasses as these are our classes.

In built-in or third party classes, things are not so easy.

We need to wrap or inherit (if we can) them to add the accept() method.

3) Indirections

The pattern creates multiples indirections.

The double dispatch means two invocations instead of a single one :

call the visited (piece) -> that calls the visitor (pieceMovingVisitor)

And we could have additional indirections as the visitor changes the visited object state.

It may look like a cycle :

call the visited (piece) -> that calls the visitor (pieceMovingVisitor) -> that calls the visited (piece)