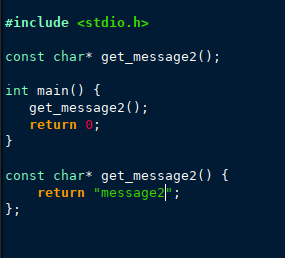

I posted an answer on a similar question (now deleted), so I will use that example here, too:

The short answer is a string literal message2 will exist in memory

as long as the process does, but in the .rodata section (assuming we are talking about an ELF file).

We return a pointer to a string constant, but as we will latter see, there is no separate memory defined anywhere which stores this const char * pointer,

and there is no need to, as the address of the string is calculated in the code and returned using the register $rax every time function is called.

But lets take a look in the code at what happens with the GNU Debugger (GDB):

![enter image description here]()

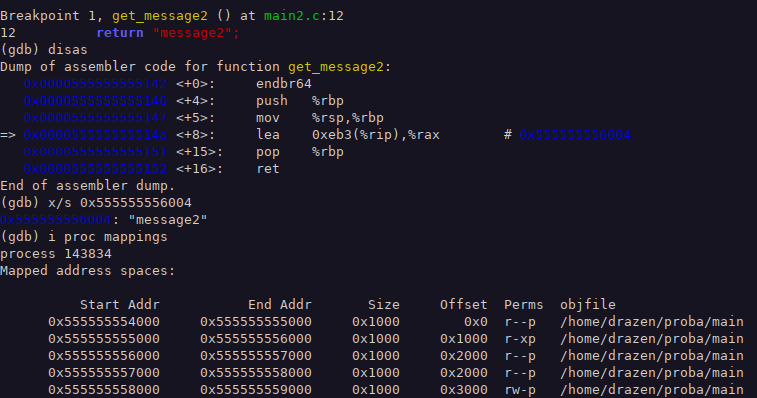

We put a breakpoint in our function returning a pointer to a constant string, and we see assembly code and a process map:

![enter image description here]()

The code gets this string in the following instruction:

0x000055555555514a <+8>: lea 0xeb3(%rip),%rax # 0x555555556004

What this instruction does is calculates the address of message2.

We see here what position independent code (PIC) means.

The address of the message2 string is not hardcoded as absolute, but is calculated as relative, as hardcoded offset 0xeb3 of the next instruction address (0x555555555151 + 0xeb3) and put in the register rax.

The purpose of relative addressing (current address +/- offset) means a process will always get the right address of message2, no matter where in memory it is loaded.

So here we see that const char * that you asked for actually doesn't exist in memory, because the address is calculated "on the fly" and returned using $rax:

We have the address in $rax:

(gdb) i r $rax

rax 0x555555556004 93824992239620

And it holds the address of message2:

(gdb) x/s 0x555555556004

0x555555556004: "message2"

Now let's see where the address 0x555555556004 is in the process address map:

0x555555556000 0x555555557000 0x1000 0x2000 r--p /home/drazen/proba/main

So this section is not executable and not writable, just readable and private (r--p) which makes sense as this is not a shared library.

When we check with readelf it shows that it is in the .rodata section of the ELF file:

drazen@HP-ProBook-640G1:~/proba$ readelf -x .rodata main

Hex dump of section '.rodata':

0x00002000 01000200 6d657373 61676532 00 ....message2.

So the answer is that this string will not be hardcoded in a code segment .text of the ELF file, the read-only data segment .rodata, but yes it will exist as long the process exists in memory.

And just to add one small detail, this constant string will be returned to the main() function by reference, of course (address), but not on the stack; rather in the register rax:

(gdb) i r

rax 0x555555556004 93824992239620

rbx 0x0