How can I set, clear, and toggle a bit?

Setting a bit

Use the bitwise OR operator (|) to set nth bit of number to 1.

// Can be whatever unsigned integer type you want, but

// it's important to use the same type everywhere to avoid

// performance issues caused by mixing integer types.

typedef unsigned long Uint;

// In C++, this can be template.

// In C11, you can make it generic with _Generic, or with macros prior to C11.

inline Uint bit_set(Uint number, Uint n) {

return number | ((Uint)1 << n);

}

Note that it's undefined behavior to shift by more than the width of a Uint. The same applies to all remaining examples.

Clearing a bit

Use the bitwise AND operator (&) to set the nth bit of number to 0.

inline Uint bit_clear(Uint number, Uint n) {

return number & ~((Uint)1 << n);

}

You must invert the bit string with the bitwise NOT operator (~), then AND it.

Toggling a bit

Use the bitwise XOR operator (^) to toggle the nth bit of number.

inline Uint bit_toggle(Uint number, Uint n) {

return number ^ ((Uint)1 << n);

}

Checking a bit

You didn't ask for this, but I might as well add it.

To check a bit, shift number n to the right, then bitwise AND it:

// bool requires #include <stdbool.h> prior to C23

inline bool bit_check(Uint number, Uint n) {

return (number >> n) & (Uint)1;

}

Changing the nth bit to x

There are alternatives with worse codegen, but the best way is to clear the bit like in bit_clear, then set the bit to value, similar to bit_set.

inline Uint bit_set_to(Uint number, Uint n, bool x) {

return (number & ~((Uint)1 << n)) | ((Uint)x << n);

}

All solutions have been tested to provide optimal codegen with GCC and clang. See https://godbolt.org/z/Wfzh8xsjW.

number is wider than int –

Idolize bit = (number >> x) & 1 –

Timoteo 1 is an int literal, which is signed. So all the operations here operate on signed numbers, which is not well defined by the standards. The standards does not guarantee two's complement or arithmetic shift so it is better to use 1U. –

Poult unsigned long long in size anyway... there may be implementation-defined extensions such as __int128 . To be ultra-safe (uintmax_t)1 << x –

Soekarno number = number & ~(1 << n) | (x << n); for Changing the n-th bit to x. –

Takao number is larger than int and n is greater or equal to the number of bits in an int. It even invokes undefined behaviour in this case. number = number & ~((uintmax_t)1 << n) | ((uintmax_t)x << n); is a generic expression that should work for all sizes of number but may generate ugly and inefficient code for smaller sizes. –

Ion -x is not safe since the C standard allows signed integers to be (e.g.) sign-magnitude, ones' complement, or any other system that can express the necessary range, meaning that -x is not required to be the same as (~x) + 1. This isn't that big of a deal on modern architectures, but you never know what a sufficiently clever optimizing compiler will do with your code. –

Graduation ~ instead ! ? –

Viceregent ~) inverts all the bits, so ~0xFFF0FFFF is 0x000F0000. Boolean not (!) gives 0 if the value is non-zero or 1 if the value is zero, so !0xFFF0FFFF is 0x00000000. –

Tsang -1 is 0b1111..1110. (All-ones is -0). C++ also allows sign/magnitude integer representations, where -x just flips the sign bit. I updated this answer to point that out. It's totally fine if you are only targeting 2's complement C++ implementations. It's not UB, it's merely implementation-defined, so it is required to work correctly on implementations the define signed integers as 2's complement. I also changed the constants to 1UL, with a note that 1ULL may be required. –

Coquetry -x is UB if x is INT_MIN. –

Graduation -(unsigned long)x which would also sidestep the signed-integer representation. (unsigned base 2 matches 2's complement semantics.) But it only works correctly if x is 0 or 1. Remember we're setting bit n to x. –

Coquetry 0U - 1U -> all-ones. How does it look now? I tried to keep the answer simple. I did mention that you may need to booleanize with !!x. If this was my own answer, I might insert more text about always using unsigned, but I'm just maintaining this old canonical answer. (Jeremy, hope you like the changes, you might want to edit to put my changes into your own words or whatever else you want to say nearly 9 years later.) –

Coquetry nth bit to x section was added by another 3rd-party edit, and wasn't Jeremy's work in the first place. –

Coquetry set bit to value operation. Generally I do the save state + unconditionally set/clear + restore state in hardware. Anyway, I randomly stumbled on this and will definitely steal the expression above. –

Karr number = (number | (1UL << n)) ^ (!x << n) Simplified to remove a logical not and a bitwise not –

Chiropodist x. Would not number = (number & ~(1UL << n)) | (x << n); generate two bit shifts, one byte flip, one AND, one OR and lastly one assignment. While if (x) { number |= (1 << n); } else { number &= ~(1 << n); } would generate one "comparison", one bit shift, either an OR or an AND with a byte flip, as well as an assignment. 6 vs 5 operations in the worst case (clearing the bit). 6 vs 4 when setting the bit. Much more readable. But maybe some ops are more costly? –

Pori x, however, when randomizing the x's value, the non-if-solution is aobut twice as fast as the if-solution: godbolt.org/z/5aEbKchzf So, yeah you are right, branch prediction kills the performance. –

Abubekr (number & (1UL << n)) != 0 (or use !! if you prefer) since this produces a boolean result rather than an integer (and this is usually done in boolean contexts such as if statements). While an integer expression is legal and will behave correctly in boolean contexts, depending on compiler settings it may produce a warning. Note that you need a slightly different expression to check a bitmask of multiple bits, depending on whether you're wanting to check for any bits or all bits. –

Hanselka Using the Standard C++ Library: std::bitset<N>.

Or the Boost version: boost::dynamic_bitset.

There isn't any need to roll your own:

#include <bitset>

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::bitset<5> x;

x[1] = 1;

x[2] = 0;

// Note x[0-4] valid

std::cout << x << std::endl;

}

./a.out

Output:

00010

The Boost version allows a runtime sized bitset compared with a standard library compile-time sized bitset.

sudo apt-get install boost-devel –

Corie The other option is to use bit fields:

struct bits {

unsigned int a:1;

unsigned int b:1;

unsigned int c:1;

};

struct bits mybits;

defines a 3-bit field (actually, it's three 1-bit felds). Bit operations now become a bit (haha) simpler:

To set or clear a bit:

mybits.b = 1;

mybits.c = 0;

To toggle a bit:

mybits.a = !mybits.a;

mybits.b = ~mybits.b;

mybits.c ^= 1; /* all work */

Checking a bit:

if (mybits.c) //if mybits.c is non zero the next line below will execute

This only works with fixed-size bit fields. Otherwise you have to resort to the bit-twiddling techniques described in previous posts.

sizeof(mybits), I get 12 (i.e. size of three ints). Is this the space allocated in memory or some bug in the sizeof function? –

Hydrolysis gcc version 4.4.5 –

Hydrolysis struct can be put inside a (usually anonymous) union with an integer etc. It works. (I realize this is an old thread btw) –

Albers __attribute__((packed)) –

Kinslow I use macros defined in a header file to handle bit set and clear:

/* a=target variable, b=bit number to act upon 0-n */

#define BIT_SET(a,b) ((a) |= (1ULL<<(b)))

#define BIT_CLEAR(a,b) ((a) &= ~(1ULL<<(b)))

#define BIT_FLIP(a,b) ((a) ^= (1ULL<<(b)))

#define BIT_CHECK(a,b) (!!((a) & (1ULL<<(b)))) // '!!' to make sure this returns 0 or 1

#define BITMASK_SET(x, mask) ((x) |= (mask))

#define BITMASK_CLEAR(x, mask) ((x) &= (~(mask)))

#define BITMASK_FLIP(x, mask) ((x) ^= (mask))

#define BITMASK_CHECK_ALL(x, mask) (!(~(x) & (mask)))

#define BITMASK_CHECK_ANY(x, mask) ((x) & (mask))

BITMASK_CHECK(x,y) ((x) & (y)) must be ((x) & (y)) == (y) otherwise it returns incorrect result on multibit mask (ex. 5 vs. 3) /*Hello to all gravediggers :)*/ –

Beachhead 1 should be (uintmax_t)1 or similar in case anybody tries to use these macros on a long or larger type –

Soekarno 1ULL works as well as (uintmax_t) on most implementations. –

Coquetry BITMASK_CHECK_ALL(x,y) can be implemented as !~((~(y))|(x)) –

Whatsoever !(~(x) & (y)) –

Friar !! by doing ((a) >> (b) & 1). This will give 0 or 1 regardless. –

Ineluctable It is sometimes worth using an enum to name the bits:

enum ThingFlags = {

ThingMask = 0x0000,

ThingFlag0 = 1 << 0,

ThingFlag1 = 1 << 1,

ThingError = 1 << 8,

}

Then use the names later on. I.e. write

thingstate |= ThingFlag1;

thingstate &= ~ThingFlag0;

if (thing & ThingError) {...}

to set, clear and test. This way you hide the magic numbers from the rest of your code.

Other than that, I endorse Paige Ruten's solution.

clearbits() function instead of &= ~. Why are you using an enum for this? I thought those were for creating a bunch of unique variables with hidden arbitrary value, but you're assigning a definite value to each one. So what's the benefit vs just defining them as variables? –

Hifalutin enums for sets of related constants goes back a long way in c programing. I suspect that with modern compilers the only advantage over const short or whatever is that they are explicitly grouped together. And when you want them for something other than bitmasks you get the automatic numbering. In c++ of course, they also form distinct types which gives you a little extras static error checking. –

Hilariohilarious enum ThingFlags value for ThingError|ThingFlag1, for example? –

Contingent int. This can cause all manner of subtle bugs because of implicit integer promotion or bitwise operations on signed types. thingstate = ThingFlag1 >> 1 will for example invoke implementation-defined behavior. thingstate = (ThingFlag1 >> x) << y can invoke undefined behavior. And so on. To be safe, always cast to an unsigned type. –

Fleuron enum My16Bits: unsigned short { ... }; –

Pitzer ThingMask zero? –

Myrta From snip-c.zip's bitops.h:

/*

** Bit set, clear, and test operations

**

** public domain snippet by Bob Stout

*/

typedef enum {ERROR = -1, FALSE, TRUE} LOGICAL;

#define BOOL(x) (!(!(x)))

#define BitSet(arg,posn) ((arg) | (1L << (posn)))

#define BitClr(arg,posn) ((arg) & ~(1L << (posn)))

#define BitTst(arg,posn) BOOL((arg) & (1L << (posn)))

#define BitFlp(arg,posn) ((arg) ^ (1L << (posn)))

OK, let's analyze things...

The common expression that you seem to be having problems with in all of these is "(1L << (posn))". All this does is create a mask with a single bit on and which will work with any integer type. The "posn" argument specifies the position where you want the bit. If posn==0, then this expression will evaluate to:

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 binary.

If posn==8, it will evaluate to:

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 0000 0000 binary.

In other words, it simply creates a field of 0's with a 1 at the specified position. The only tricky part is in the BitClr() macro where we need to set a single 0 bit in a field of 1's. This is accomplished by using the 1's complement of the same expression as denoted by the tilde (~) operator.

Once the mask is created it's applied to the argument just as you suggest, by use of the bitwise and (&), or (|), and xor (^) operators. Since the mask is of type long, the macros will work just as well on char's, short's, int's, or long's.

The bottom line is that this is a general solution to an entire class of problems. It is, of course, possible and even appropriate to rewrite the equivalent of any of these macros with explicit mask values every time you need one, but why do it? Remember, the macro substitution occurs in the preprocessor and so the generated code will reflect the fact that the values are considered constant by the compiler - i.e. it's just as efficient to use the generalized macros as to "reinvent the wheel" every time you need to do bit manipulation.

Unconvinced? Here's some test code - I used Watcom C with full optimization and without using _cdecl so the resulting disassembly would be as clean as possible:

----[ TEST.C ]----------------------------------------------------------------

#define BOOL(x) (!(!(x)))

#define BitSet(arg,posn) ((arg) | (1L << (posn)))

#define BitClr(arg,posn) ((arg) & ~(1L << (posn)))

#define BitTst(arg,posn) BOOL((arg) & (1L << (posn)))

#define BitFlp(arg,posn) ((arg) ^ (1L << (posn)))

int bitmanip(int word)

{

word = BitSet(word, 2);

word = BitSet(word, 7);

word = BitClr(word, 3);

word = BitFlp(word, 9);

return word;

}

----[ TEST.OUT (disassembled) ]-----------------------------------------------

Module: C:\BINK\tst.c

Group: 'DGROUP' CONST,CONST2,_DATA,_BSS

Segment: _TEXT BYTE 00000008 bytes

0000 0c 84 bitmanip_ or al,84H ; set bits 2 and 7

0002 80 f4 02 xor ah,02H ; flip bit 9 of EAX (bit 1 of AH)

0005 24 f7 and al,0f7H

0007 c3 ret

No disassembly errors

----[ finis ]-----------------------------------------------------------------

arg is long long. 1L needs to be the widest possible type, so (uintmax_t)1 . (You might get away with 1ull) –

Soekarno For the beginner I would like to explain a bit more with an example:

Example:

value is 0x55;

bitnum : 3rd.

The & operator is used check the bit:

0101 0101

&

0000 1000

___________

0000 0000 (mean 0: False). It will work fine if the third bit is 1 (then the answer will be True)

Toggle or Flip:

0101 0101

^

0000 1000

___________

0101 1101 (Flip the third bit without affecting other bits)

| operator: set the bit

0101 0101

|

0000 1000

___________

0101 1101 (set the third bit without affecting other bits)

Here's my favorite bit arithmetic macro, which works for any type of unsigned integer array from unsigned char up to size_t (which is the biggest type that should be efficient to work with):

#define BITOP(a,b,op) \

((a)[(size_t)(b)/(8*sizeof *(a))] op ((size_t)1<<((size_t)(b)%(8*sizeof *(a)))))

To set a bit:

BITOP(array, bit, |=);

To clear a bit:

BITOP(array, bit, &=~);

To toggle a bit:

BITOP(array, bit, ^=);

To test a bit:

if (BITOP(array, bit, &)) ...

etc.

BITOP(array, bit++, |=); in a loop will most likely not do what the caller wants. –

Rotor BITCELL(a,b) |= BITMASK(a,b); (both take a as an argument to determine the size, but the latter would never evaluate a since it appears only in sizeof). –

Covert (size_t) cast seem to be there only to insure some unsigned math with %. Could (unsigned) there. –

Gabbert (size_t)(b)/(8*sizeof *(a)) unnecessarily could narrow b before the division. Only an issue with very large bit arrays. Still an interesting macro. –

Gabbert As this is tagged "embedded" I'll assume you're using a microcontroller. All of the above suggestions are valid & work (read-modify-write, unions, structs, etc.).

However, during a bout of oscilloscope-based debugging I was amazed to find that these methods have a considerable overhead in CPU cycles compared to writing a value directly to the micro's PORTnSET / PORTnCLEAR registers which makes a real difference where there are tight loops / high-frequency ISR's toggling pins.

For those unfamiliar: In my example, the micro has a general pin-state register PORTn which reflects the output pins, so doing PORTn |= BIT_TO_SET results in a read-modify-write to that register. However, the PORTnSET / PORTnCLEAR registers take a '1' to mean "please make this bit 1" (SET) or "please make this bit zero" (CLEAR) and a '0' to mean "leave the pin alone". so, you end up with two port addresses depending whether you're setting or clearing the bit (not always convenient) but a much faster reaction and smaller assembled code.

volatile and therefore the compiler is unable to perform any optimizations on code involving such registers. Therefore, it is good practice to disassemble such code and see how it turned out on assembler level. –

Fleuron Let’s suppose a few things first:

num = 55: An integer to perform bitwise operations (set, get, clear, and toggle).

n = 4: 0-based bit position to perform bitwise operations.

How can we get a bit?

To get the nth bit of num, right shift num, n times. Then perform a bitwise AND & with 1.

bit = (num >> n) & 1;

How does it work?

0011 0111 (55 in decimal)

>> 4 (right shift 4 times)

-----------------

0000 0011

& 0000 0001 (1 in decimal)

-----------------

=> 0000 0001 (final result)

How can we set a bit?

To set a particular bit of number, left shift 1 n times. Then perform a bitwise OR | operation with num.

num |= 1 << n; // Equivalent to num = (1 << n) | num;

How does it work?

0000 0001 (1 in decimal)

<< 4 (left shift 4 times)

-----------------

0001 0000

| 0011 0111 (55 in decimal)

-----------------

=> 0001 0000 (final result)

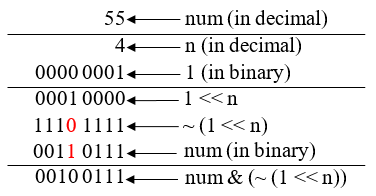

How can we clear a bit?

- Left shift 1,

ntimes, i.e.,1 << n. - Perform a bitwise complement with the above result. So that the nth bit becomes unset and the rest of the bits become set, i.e.,

~ (1 << n). - Finally, perform a bitwise AND

&operation with the above result andnum. The above three steps together can be written asnum & (~ (1 << n));

num &= ~(1 << n); // Equivalent to num = num & ~(1 << n);

How does it work?

0000 0001 (1 in decimal)

<< 4 (left shift 4 times)

-----------------

~ 0001 0000

-----------------

1110 1111

& 0011 0111 (55 in decimal)

-----------------

=> 0010 0111 (final result)

How can we toggle a bit?

To toggle a bit, we use bitwise XOR ^ operator. Bitwise XOR operator evaluates to 1 if the corresponding bit of both operands are different. Otherwise, it evaluates to 0.

Which means to toggle a bit, we need to perform an XOR operation with the bit you want to toggle and 1.

num ^= 1 << n; // Equivalent to num = num ^ (1 << n);

How does it work?

- If the bit to toggle is 0 then,

0 ^ 1 => 1. - If the bit to toggle is 1 then,

1 ^ 1 => 0.

0000 0001 (1 in decimal)

<< 4 (left shift 4 times)

-----------------

0001 0000

^ 0011 0111 (55 in decimal)

-----------------

=> 0010 0111 (final result)

The bitfield approach has other advantages in the embedded arena. You can define a struct that maps directly onto the bits in a particular hardware register.

struct HwRegister {

unsigned int errorFlag:1; // one-bit flag field

unsigned int Mode:3; // three-bit mode field

unsigned int StatusCode:4; // four-bit status code

};

struct HwRegister CR3342_AReg;

You need to be aware of the bit packing order - I think it's MSB first, but this may be implementation-dependent. Also, verify how your compiler handlers fields crossing byte boundaries.

You can then read, write, test the individual values as before.

Check a bit at an arbitrary location in a variable of arbitrary type:

#define bit_test(x, y) ( ( ((const char*)&(x))[(y)>>3] & 0x80 >> ((y)&0x07)) >> (7-((y)&0x07) ) )

Sample usage:

int main(void)

{

unsigned char arr[8] = { 0x01, 0x23, 0x45, 0x67, 0x89, 0xAB, 0xCD, 0xEF };

for (int ix = 0; ix < 64; ++ix)

printf("bit %d is %d\n", ix, bit_test(arr, ix));

return 0;

}

Notes: This is designed to be fast (given its flexibility) and non-branchy. It results in efficient SPARC machine code when compiled Sun Studio 8; I've also tested it using MSVC++ 2008 on amd64. It's possible to make similar macros for setting and clearing bits. The key difference of this solution compared with many others here is that it works for any location in pretty much any type of variable.

More general, for arbitrary sized bitmaps:

#define BITS 8

#define BIT_SET( p, n) (p[(n)/BITS] |= (0x80>>((n)%BITS)))

#define BIT_CLEAR(p, n) (p[(n)/BITS] &= ~(0x80>>((n)%BITS)))

#define BIT_ISSET(p, n) (p[(n)/BITS] & (0x80>>((n)%BITS)))

CHAR_BIT is already defined by limits.h, you don't need to put in your own BITS (and in fact you make your code worse by doing so) –

Soekarno This program is to change any data bit from 0 to 1 or 1 to 0:

{

unsigned int data = 0x000000F0;

int bitpos = 4;

int bitvalue = 1;

unsigned int bit = data;

bit = (bit>>bitpos)&0x00000001;

int invbitvalue = 0x00000001&(~bitvalue);

printf("%x\n",bit);

if (bitvalue == 0)

{

if (bit == 0)

printf("%x\n", data);

else

{

data = (data^(invbitvalue<<bitpos));

printf("%x\n", data);

}

}

else

{

if (bit == 1)

printf("elseif %x\n", data);

else

{

data = (data|(bitvalue<<bitpos));

printf("else %x\n", data);

}

}

}

If you're doing a lot of bit twiddling you might want to use masks which will make the whole thing quicker. The following functions are very fast and are still flexible (they allow bit twiddling in bit maps of any size).

const unsigned char TQuickByteMask[8] =

{

0x01, 0x02, 0x04, 0x08,

0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x80,

};

/** Set bit in any sized bit mask.

*

* @return none

*

* @param bit - Bit number.

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

*/

void TSetBit( short bit, unsigned char *bitmap)

{

short n, x;

x = bit / 8; // Index to byte.

n = bit % 8; // Specific bit in byte.

bitmap[x] |= TQuickByteMask[n]; // Set bit.

}

/** Reset bit in any sized mask.

*

* @return None

*

* @param bit - Bit number.

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

*/

void TResetBit( short bit, unsigned char *bitmap)

{

short n, x;

x = bit / 8; // Index to byte.

n = bit % 8; // Specific bit in byte.

bitmap[x] &= (~TQuickByteMask[n]); // Reset bit.

}

/** Toggle bit in any sized bit mask.

*

* @return none

*

* @param bit - Bit number.

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

*/

void TToggleBit( short bit, unsigned char *bitmap)

{

short n, x;

x = bit / 8; // Index to byte.

n = bit % 8; // Specific bit in byte.

bitmap[x] ^= TQuickByteMask[n]; // Toggle bit.

}

/** Checks specified bit.

*

* @return 1 if bit set else 0.

*

* @param bit - Bit number.

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

*/

short TIsBitSet( short bit, const unsigned char *bitmap)

{

short n, x;

x = bit / 8; // Index to byte.

n = bit % 8; // Specific bit in byte.

// Test bit (logigal AND).

if (bitmap[x] & TQuickByteMask[n])

return 1;

return 0;

}

/** Checks specified bit.

*

* @return 1 if bit reset else 0.

*

* @param bit - Bit number.

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

*/

short TIsBitReset( short bit, const unsigned char *bitmap)

{

return TIsBitSet(bit, bitmap) ^ 1;

}

/** Count number of bits set in a bitmap.

*

* @return Number of bits set.

*

* @param bitmap - Pointer to bitmap.

* @param size - Bitmap size (in bits).

*

* @note Not very efficient in terms of execution speed. If you are doing

* some computationally intense stuff you may need a more complex

* implementation which would be faster (especially for big bitmaps).

* See (http://graphics.stanford.edu/~seander/bithacks.html).

*/

int TCountBits( const unsigned char *bitmap, int size)

{

int i, count = 0;

for (i=0; i<size; i++)

if (TIsBitSet(i, bitmap))

count++;

return count;

}

Note, to set bit 'n' in a 16 bit integer you do the following:

TSetBit( n, &my_int);

It's up to you to ensure that the bit number is within the range of the bit map that you pass. Note that for little endian processors that bytes, words, dwords, qwords, etc., map correctly to each other in memory (main reason that little endian processors are 'better' than big-endian processors, ah, I feel a flame war coming on...).

Use this:

int ToggleNthBit ( unsigned char n, int num )

{

if(num & (1 << n))

num &= ~(1 << n);

else

num |= (1 << n);

return num;

}

Expanding on the bitset answer:

#include <iostream>

#include <bitset>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

bitset<8> byte(std::string("10010011");

// Set Bit

byte.set(3); // 10010111

// Clear Bit

byte.reset(2); // 10010101

// Toggle Bit

byte.flip(7); // 00010101

cout << byte << endl;

return 0;

}

If you want to perform this all operation with C programming in the Linux kernel then I suggest to use standard APIs of the Linux kernel.

See Chapter 2. Basic C Library Functions

set_bit Atomically set a bit in memory

clear_bit Clears a bit in memory

change_bit Toggle a bit in memory

test_and_set_bit Set a bit and return its old value

test_and_clear_bit Clear a bit and return its old value

test_and_change_bit Change a bit and return its old value

test_bit Determine whether a bit is set

Note: Here the whole operation happens in a single step. So these all are guaranteed to be atomic even on SMP computers and are useful to keep coherence across processors.

Visual C 2010, and perhaps many other compilers, have direct support for boolean operations built in. A bit has two possible values, just like a Boolean, so we can use Booleans instead—even if they take up more space than a single bit in memory in this representation. This works, and even the sizeof() operator works properly.

bool IsGph[256], IsNotGph[256];

// Initialize boolean array to detect printable characters

for(i=0; i<sizeof(IsGph); i++) {

IsGph[i] = isgraph((unsigned char)i);

}

So, to your question, IsGph[i] =1, or IsGph[i] =0 make setting and clearing bools easy.

To find unprintable characters:

// Initialize boolean array to detect UN-printable characters,

// then call function to toggle required bits true, while initializing a 2nd

// boolean array as the complement of the 1st.

for(i=0; i<sizeof(IsGph); i++) {

if(IsGph[i]) {

IsNotGph[i] = 0;

}

else {

IsNotGph[i] = 1;

}

}

Note there isn't anything "special" about this code. It treats a bit like an integer—which technically, it is. A 1 bit integer that can hold two values, and two values only.

I once used this approach to find duplicate loan records, where loan_number was the ISAM key, using the six-digit loan number as an index into the bit array. It was savagely fast, and after eight months, proved that the mainframe system we were getting the data from was in fact malfunctioning. The simplicity of bit arrays makes confidence in their correctness very high—vs a searching approach for example.

bool. Maybe even 4 bytes for C89 setups that use int to implement bool –

Soekarno int set_nth_bit(int num, int n){

return (num | 1 << n);

}

int clear_nth_bit(int num, int n){

return (num & ~( 1 << n));

}

int toggle_nth_bit(int num, int n){

return num ^ (1 << n);

}

int check_nth_bit(int num, int n){

return num & (1 << n);

}

check_nth_bit can be bool. –

Crosby How do you set, clear, and toggle a single bit?

To address a common coding pitfall when attempting to form the mask:

1 is not always wide enough

What problems happen when number is a wider type than 1?

x may be too great for the shift 1 << x leading to undefined behavior (UB). Even if x is not too great, ~ may not flip enough most-significant-bits.

// Assume 32 bit int/unsigned

unsigned long long number = foo();

unsigned x = 40;

number |= (1 << x); // UB

number ^= (1 << x); // UB

number &= ~(1 << x); // UB

x = 10;

number &= ~(1 << x); // Wrong mask, not wide enough

To insure 1 is wide enough:

Code could use 1ull or pedantically (uintmax_t)1 and let the compiler optimize.

number |= (1ull << x);

number |= ((uintmax_t)1 << x);

Or cast - which makes for coding/review/maintenance issues keeping the cast correct and up-to-date.

number |= (type_of_number)1 << x;

Or gently promote the 1 by forcing a math operation that is as least as wide as the type of number.

number |= (number*0 + 1) << x;

As with most bit manipulations, it is best to work with unsigned types rather than signed ones.

number |= (type_of_number)1 << x; nor number |= (number*0 + 1) << x; appropriate to set the sign bit of a signed type... As a matter of fact, neither is number |= (1ull << x);. Is there a portable way to do it by position? –

Ion Here are some macros I use:

SET_FLAG(Status, Flag) ((Status) |= (Flag))

CLEAR_FLAG(Status, Flag) ((Status) &= ~(Flag))

INVALID_FLAGS(ulFlags, ulAllowed) ((ulFlags) & ~(ulAllowed))

TEST_FLAGS(t,ulMask, ulBit) (((t)&(ulMask)) == (ulBit))

IS_FLAG_SET(t,ulMask) TEST_FLAGS(t,ulMask,ulMask)

IS_FLAG_CLEAR(t,ulMask) TEST_FLAGS(t,ulMask,0)

This program is based out of Jeremy's solution. If someone wish to quickly play around.

public class BitwiseOperations {

public static void main(String args[]) {

setABit(0, 4); // Set the 4th bit, 0000 -> 1000 [8]

clearABit(16, 5); // Clear the 5th bit, 10000 -> 00000 [0]

toggleABit(8, 4); // Toggle the 4th bit, 1000 -> 0000 [0]

checkABit(8, 4); // Check the 4th bit 1000 -> true

}

public static void setABit(int input, int n) {

input = input | (1 << n-1);

System.out.println(input);

}

public static void clearABit(int input, int n) {

input = input & ~(1 << n-1);

System.out.println(input);

}

public static void toggleABit(int input, int n) {

input = input ^ (1 << n-1);

System.out.println(input);

}

public static void checkABit(int input, int n) {

boolean isSet = ((input >> n-1) & 1) == 1;

System.out.println(isSet);

}

}

Output:

8

0

0

true

A templated version (put in a header file) with support for changing multiple bits (works on AVR microcontrollers btw):

namespace bit {

template <typename T1, typename T2>

constexpr inline T1 bitmask(T2 bit)

{return (T1)1 << bit;}

template <typename T1, typename T3, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline T1 bitmask(T3 bit, T2 ...bits)

{return ((T1)1 << bit) | bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Set these bits (others retain their state) */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline void set (T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{variable |= bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Set only these bits (others will be cleared) */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline void setOnly (T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{variable = bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Clear these bits (others retain their state) */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline void clear (T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{variable &= ~bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Flip these bits (others retain their state) */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline void flip (T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{variable ^= bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Check if any of these bits are set */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline bool isAnySet(const T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{return variable & bitmask<T1>(bits...);}

/** Check if all these bits are set */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline bool isSet (const T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{return ((variable & bitmask<T1>(bits...)) == bitmask<T1>(bits...));}

/** Check if all these bits are not set */

template <typename T1, typename ...T2>

constexpr inline bool isNotSet (const T1 &variable, T2 ...bits)

{return ((variable & bitmask<T1>(bits...)) != bitmask<T1>(bits...));}

}

Example of use:

#include <iostream>

#include <bitset> // for console output of binary values

// and include the code above of course

using namespace std;

int main() {

uint8_t v = 0b1111'1100;

bit::set(v, 0);

cout << bitset<8>(v) << endl;

bit::clear(v, 0,1);

cout << bitset<8>(v) << endl;

bit::flip(v, 0,1);

cout << bitset<8>(v) << endl;

bit::clear(v, 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7);

cout << bitset<8>(v) << endl;

bit::flip(v, 0,7);

cout << bitset<8>(v) << endl;

}

BTW: It turns out that constexpr and inline is not used if not sending the optimizer argument (e.g.: -O3) to the compiler. Feel free to try the code at https://godbolt.org/ and look at the ASM output.

std::bitsetin c++11 –

Soso Here is a routine in C to perform the basic bitwise operations:

#define INT_BIT (unsigned int) (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8U) //number of bits in unsigned int

int main(void)

{

unsigned int k = 5; //k is the bit position; here it is the 5th bit from the LSb (0th bit)

unsigned int regA = 0x00007C7C; //we perform bitwise operations on regA

regA |= (1U << k); //Set kth bit

regA &= ~(1U << k); //Clear kth bit

regA ^= (1U << k); //Toggle kth bit

regA = (regA << k) | regA >> (INT_BIT - k); //Rotate left by k bits

regA = (regA >> k) | regA << (INT_BIT - k); //Rotate right by k bits

return 0;

}

Setting the nth bit to x (bit value) without using -1

Sometimes when you are not sure what -1 or the like will result in, you may wish to set the nth bit without using -1:

number = (((number | (1 << n)) ^ (1 << n))) | (x << n);

Explanation: ((number | (1 << n) sets the nth bit to 1 (where | denotes bitwise OR), then with (...) ^ (1 << n) we set the nth bit to 0, and finally with (...) | x << n) we set the nth bit that was 0, to (bit value) x.

This also works in Go.

(number & ~(1 << n)) | (!!x << n). –

Contortion Try one of these functions in the C language to change n bit:

char bitfield;

// Start at 0th position

void chang_n_bit(int n, int value)

{

bitfield = (bitfield | (1 << n)) & (~( (1 << n) ^ (value << n) ));

}

Or

void chang_n_bit(int n, int value)

{

bitfield = (bitfield | (1 << n)) & ((value << n) | ((~0) ^ (1 << n)));

}

Or

void chang_n_bit(int n, int value)

{

if(value)

bitfield |= 1 << n;

else

bitfield &= ~0 ^ (1 << n);

}

char get_n_bit(int n)

{

return (bitfield & (1 << n)) ? 1 : 0;

}

value << n may cause undefined behaviour –

Soekarno 1 to 0x1 or 1UL to avoid UB @Soekarno is talking about –

Pitchman © 2022 - 2024 — McMap. All rights reserved.