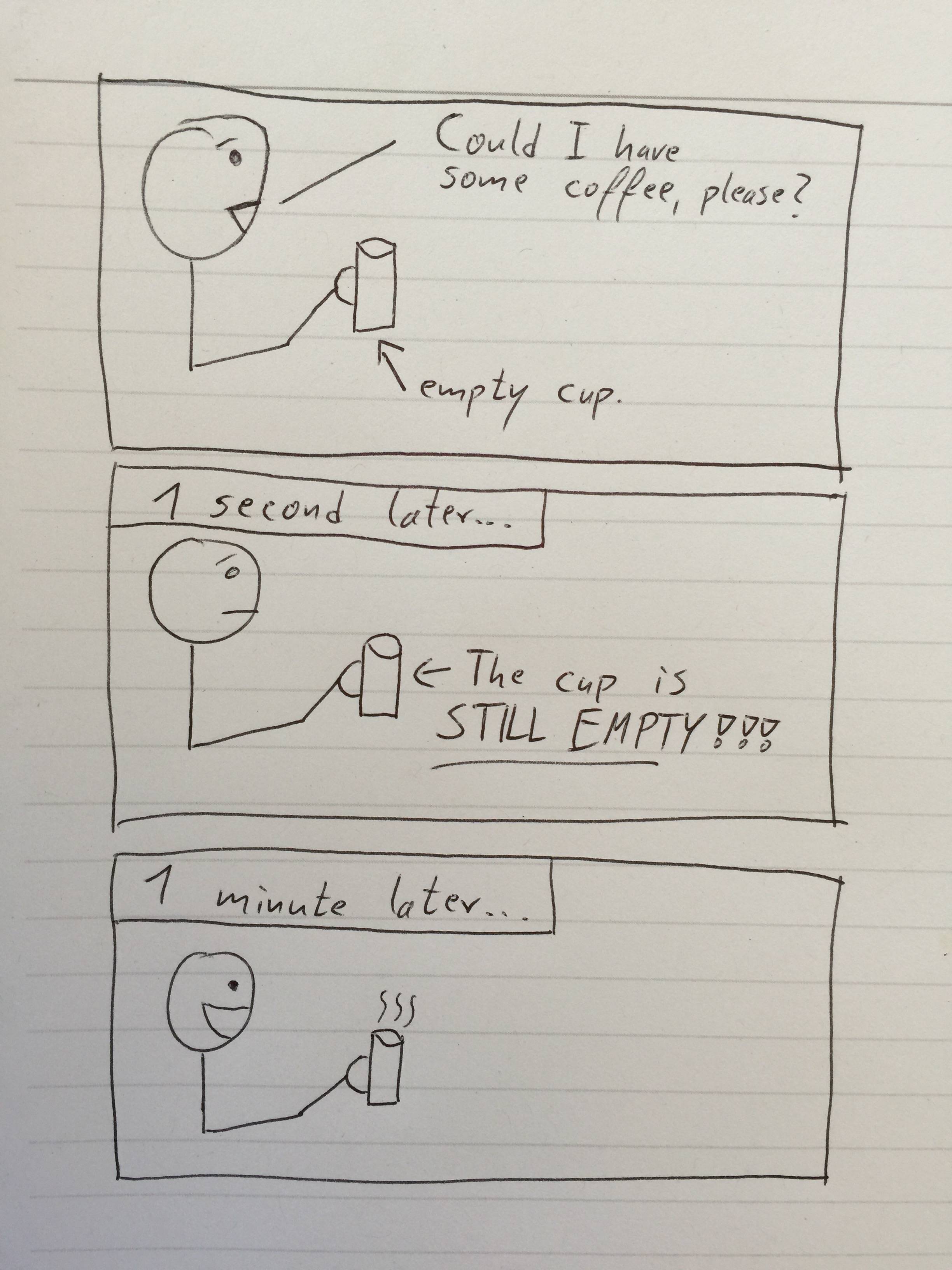

Fabrício's answer is spot on; but I wanted to complement his answer with something less technical, which focusses on an analogy to help explain the concept of asynchronicity.

An Analogy...

Yesterday, the work I was doing required some information from a colleague. I rang him up; here's how the conversation went:

Me: Hi Bob, I need to know how we foo'd the bar'd last week. Jim wants a report on it, and you're the only one who knows the details about it.

Bob: Sure thing, but it'll take me around 30 minutes?

Me: That's great Bob. Give me a ring back when you've got the information!

At this point, I hung up the phone. Since I needed information from Bob to complete my report, I left the report and went for a coffee instead, then I caught up on some email. 40 minutes later (Bob is slow), Bob called back and gave me the information I needed. At this point, I resumed my work with my report, as I had all the information I needed.

Imagine if the conversation had gone like this instead;

Me: Hi Bob, I need to know how we foo'd the bar'd last week. Jim want's a report on it, and you're the only one who knows the details about it.

Bob: Sure thing, but it'll take me around 30 minutes?

Me: That's great Bob. I'll wait.

And I sat there and waited. And waited. And waited. For 40 minutes. Doing nothing but waiting. Eventually, Bob gave me the information, we hung up, and I completed my report. But I'd lost 40 minutes of productivity.

This is asynchronous vs. synchronous behavior

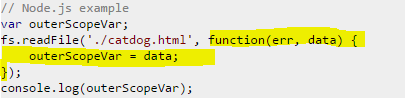

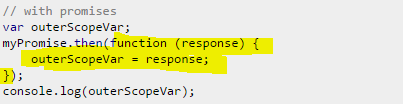

This is exactly what is happening in all the examples in our question. Loading an image, loading a file off disk, and requesting a page via AJAX are all slow operations (in the context of modern computing).

Rather than waiting for these slow operations to complete, JavaScript lets you register a callback function which will be executed when the slow operation has completed. In the meantime, however, JavaScript will continue to execute other code. The fact that JavaScript executes other code whilst waiting for the slow operation to complete makes the behaviorasynchronous. Had JavaScript waited around for the operation to complete before executing any other code, this would have been synchronous behavior.

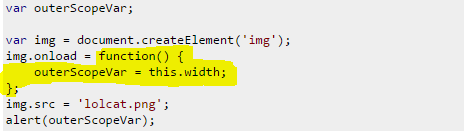

var outerScopeVar;

var img = document.createElement('img');

// Here we register the callback function.

img.onload = function() {

// Code within this function will be executed once the image has loaded.

outerScopeVar = this.width;

};

// But, while the image is loading, JavaScript continues executing, and

// processes the following lines of JavaScript.

img.src = 'lolcat.png';

alert(outerScopeVar);

In the code above, we're asking JavaScript to load lolcat.png, which is a sloooow operation. The callback function will be executed once this slow operation has done, but in the meantime, JavaScript will keep processing the next lines of code; i.e. alert(outerScopeVar).

This is why we see the alert showing undefined; since the alert() is processed immediately, rather than after the image has been loaded.

In order to fix our code, all we have to do is move the alert(outerScopeVar) code into the callback function. As a consequence of this, we no longer need the outerScopeVar variable declared as a global variable.

var img = document.createElement('img');

img.onload = function() {

var localScopeVar = this.width;

alert(localScopeVar);

};

img.src = 'lolcat.png';

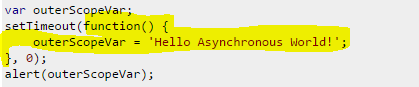

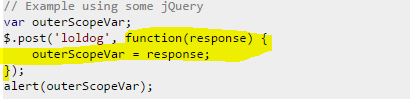

You'll always see a callback is specified as a function, because that's the only* way in JavaScript to define some code, but not execute it until later.

Therefore, in all of our examples, the function() { /* Do something */ } is the callback; to fix all the examples, all we have to do is move the code which needs the response of the operation into there!

* Technically you can use eval() as well, but eval() is evil for this purpose

How do I keep my caller waiting?

You might currently have some code similar to this;

function getWidthOfImage(src) {

var outerScopeVar;

var img = document.createElement('img');

img.onload = function() {

outerScopeVar = this.width;

};

img.src = src;

return outerScopeVar;

}

var width = getWidthOfImage('lolcat.png');

alert(width);

However, we now know that the return outerScopeVar happens immediately; before the onload callback function has updated the variable. This leads to getWidthOfImage() returning undefined, and undefined being alerted.

To fix this, we need to allow the function calling getWidthOfImage() to register a callback, then move the alert'ing of the width to be within that callback;

function getWidthOfImage(src, cb) {

var img = document.createElement('img');

img.onload = function() {

cb(this.width);

};

img.src = src;

}

getWidthOfImage('lolcat.png', function (width) {

alert(width);

});

... as before, note that we've been able to remove the global variables (in this case width).