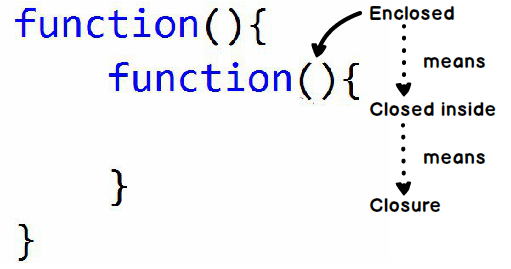

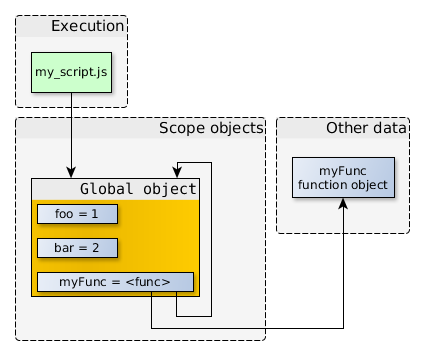

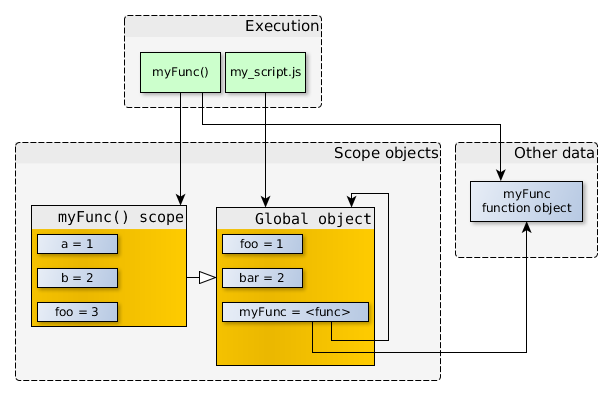

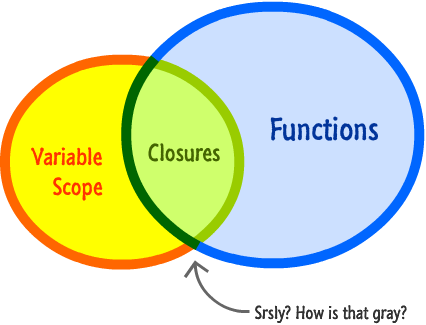

Closures are a somewhat advanced, and often misunderstood feature of the JavaScript language. Simply put, closures are objects that contain a function and a reference to the environment in which the function was created. However, in order to fully understand closures, there are two other features of the JavaScript language that must first be understood―first-class functions and inner functions.

First-Class Functions

In programming languages, functions are considered to be first-class citizens if they can be manipulated like any other data type. For example, first-class functions can be constructed at runtime and assigned to variables. They can also be passed to, and returned by other functions. In addition to meeting the previously mentioned criteria, JavaScript functions also have their own properties and methods. The following example shows some of the capabilities of first-class functions. In the example, two functions are created and assigned to the variables “foo” and “bar”. The function stored in “foo” displays a dialog box, while “bar” simply returns whatever argument is passed to it. The last line of the example does several things. First, the function stored in “bar” is called with “foo” as its argument. “bar” then returns the “foo” function reference. Finally, the returned “foo” reference is called, causing “Hello World!” to be displayed.

var foo = function() {

alert("Hello World!");

};

var bar = function(arg) {

return arg;

};

bar(foo)();

Inner Functions

Inner functions, also referred to as nested functions, are functions that are defined inside of another function (referred to as the outer function). Each time the outer function is called, an instance of the inner function is created. The following example shows how inner functions are used. In this case, add() is the outer function. Inside of add(), the doAdd() inner function is defined and called.

function add(value1, value2) {

function doAdd(operand1, operand2) {

return operand1 + operand2;

}

return doAdd(value1, value2);

}

var foo = add(1, 2);

// foo equals 3

One important characteristic of inner functions is that they have implicit access to the outer function’s scope. This means that the inner function can use the variables, arguments, etc. of the outer function. In the previous example, the “value1” and “value2” arguments of add() were passed to doAdd() as the “operand1” and “operand2” arguments. However, this is unnecessary because doAdd() has direct access to “value1” and “value2”. The previous example has been rewritten below to show how doAdd() can use “value1” and “value2”.

function add(value1, value2) {

function doAdd() {

return value1 + value2;

}

return doAdd();

}

var foo = add(1, 2);

// foo equals 3

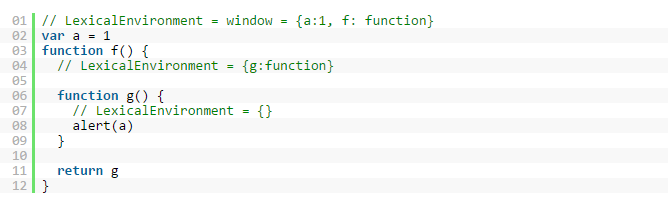

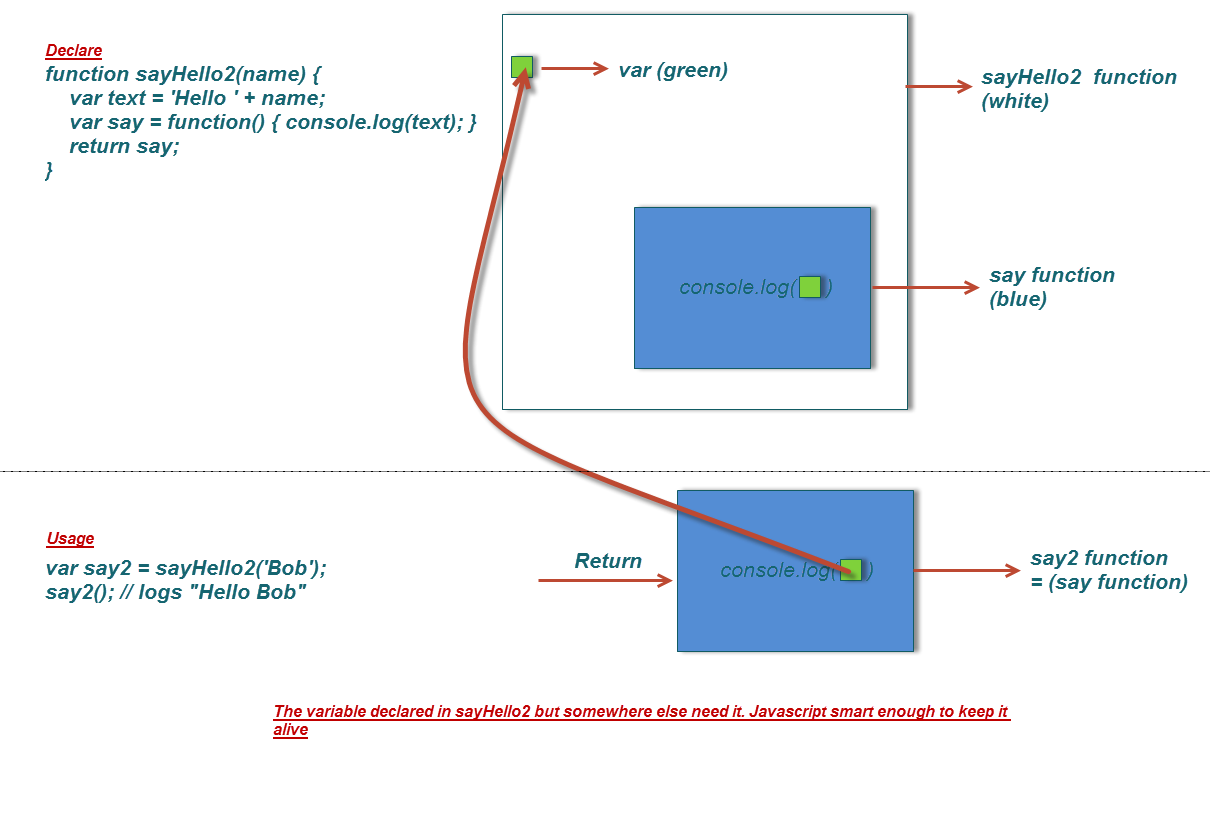

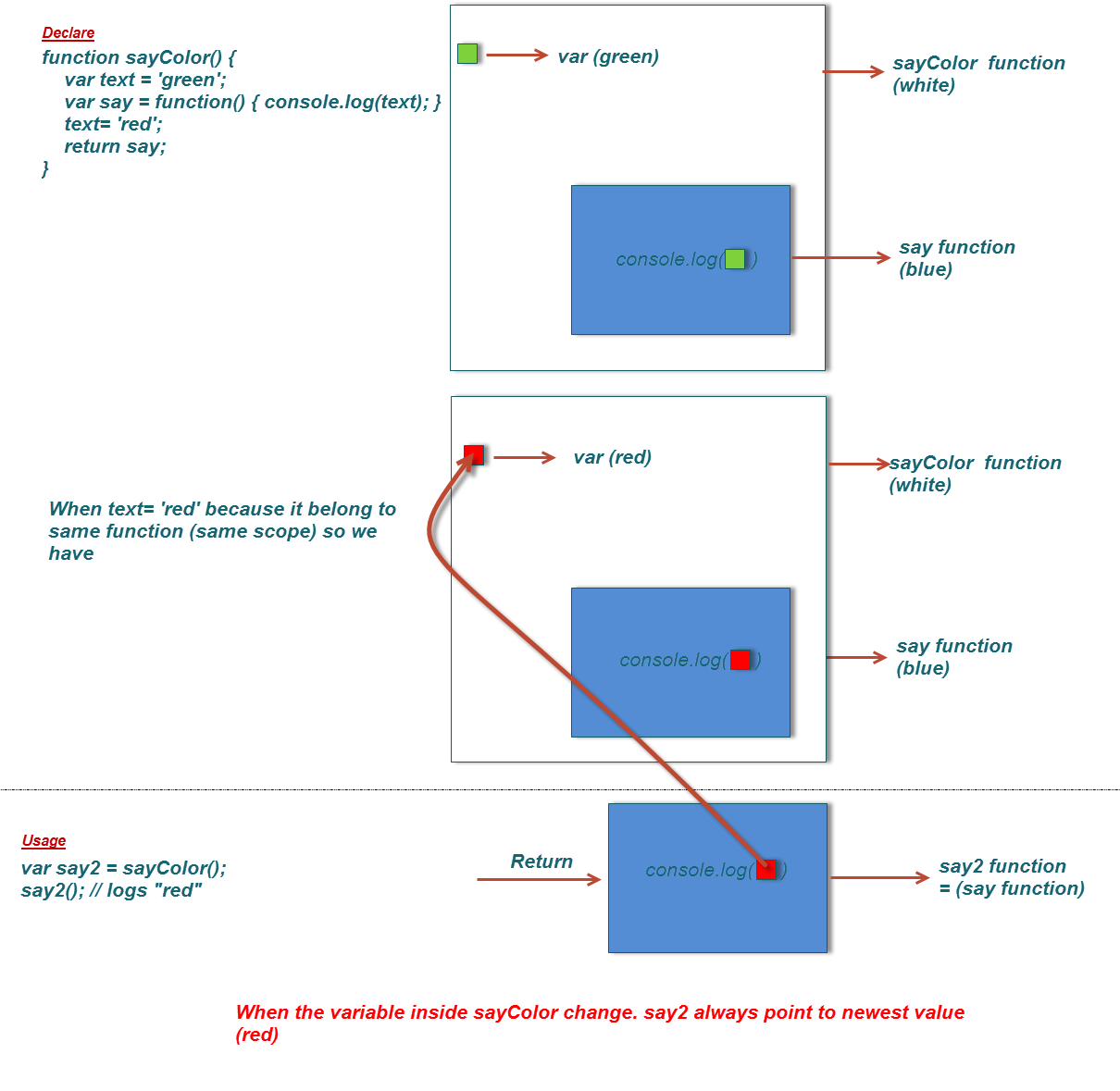

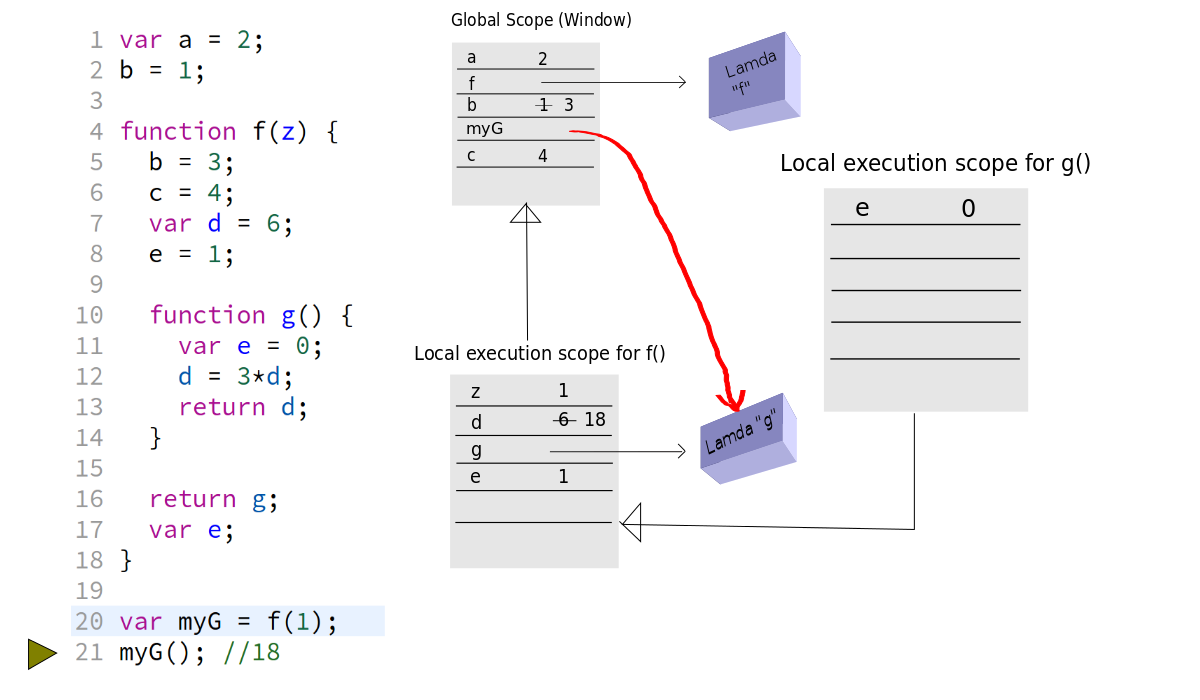

Creating Closures

A closure is created when an inner function is made accessible from

outside of the function that created it. This typically occurs when an

outer function returns an inner function. When this happens, the

inner function maintains a reference to the environment in which it

was created. This means that it remembers all of the variables (and

their values) that were in scope at the time. The following example

shows how a closure is created and used.

function add(value1) {

return function doAdd(value2) {

return value1 + value2;

};

}

var increment = add(1);

var foo = increment(2);

// foo equals 3

There are a number of things to note about this example.

The add() function returns its inner function doAdd(). By returning a reference to an inner function, a closure is created.

“value1” is a local variable of add(), and a non-local variable of doAdd(). Non-local variables refer to variables that are neither in the local nor the global scope. “value2” is a local variable of doAdd().

When add(1) is called, a closure is created and stored in “increment”. In the closure’s referencing environment, “value1” is bound to the value one. Variables that are bound are also said to be closed over. This is where the name closure comes from.

When increment(2) is called, the closure is entered. This means that doAdd() is called, with the “value1” variable holding the value one. The closure can essentially be thought of as creating the following function.

function increment(value2) {

return 1 + value2;

}

When to Use Closures

Closures can be used to accomplish many things. They are very useful

for things like configuring callback functions with parameters. This

section covers two scenarios where closures can make your life as a

developer much simpler.

Working With Timers

Closures are useful when used in conjunction with the setTimeout() and setInterval() functions. To be more specific, closures allow you to pass arguments to the callback functions of setTimeout() and setInterval(). For example, the following code prints the string “some message” once per second by calling showMessage().

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Closures</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<script>

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

window.setInterval(showMessage, 1000, "some message<br />");

});

function showMessage(message) {

document.getElementById("message").innerHTML += message;

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<span id="message"></span>

</body>

</html>

Unfortunately, Internet Explorer does not support passing callback arguments via setInterval(). Instead of displaying “some message”, Internet Explorer displays “undefined” (since no value is actually passed to showMessage()). To work around this issue, a closure can be created which binds the “message” argument to the desired value. The closure can then be used as the callback function for setInterval(). To illustrate this concept, the JavaScript code from the previous example has been rewritten below to use a closure.

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

var showMessage = getClosure("some message<br />");

window.setInterval(showMessage, 1000);

});

function getClosure(message) {

function showMessage() {

document.getElementById("message").innerHTML += message;

}

return showMessage;

}

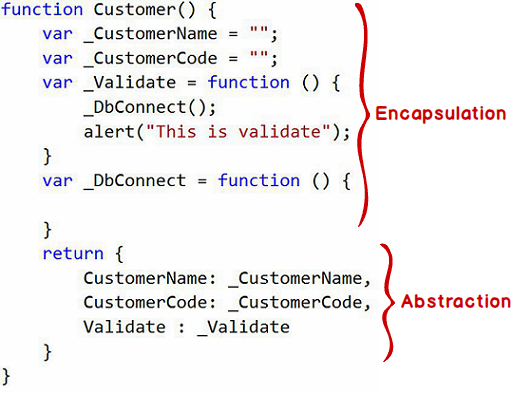

Emulating Private Data

Many object-oriented languages support the concept of private member data. However, JavaScript is not a pure object-oriented language and does not support private data. But, it is possible to emulate private data using closures. Recall that a closure contains a reference to the environment in which it was originally created―which is now out of scope. Since the variables in the referencing environment are only accessible from the closure function, they are essentially private data.

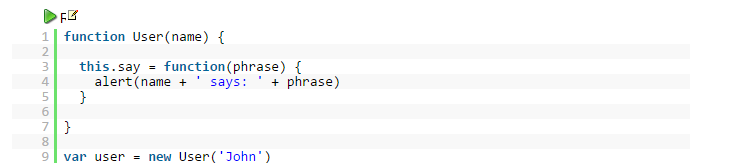

The following example shows a constructor for a simple Person class. When each Person is created, it is given a name via the “name” argument. Internally, the Person stores its name in the “_name” variable. Following good object-oriented programming practices, the method getName() is also provided for retrieving the name.

function Person(name) {

this._name = name;

this.getName = function() {

return this._name;

};

}

There is still one major problem with the Person class. Because JavaScript does not support private data, there is nothing stopping somebody else from coming along and changing the name. For example, the following code creates a Person named Colin, and then changes its name to Tom.

var person = new Person("Colin");

person._name = "Tom";

// person.getName() now returns "Tom"

Personally, I wouldn’t like it if just anyone could come along and legally change my name. In order to stop this from happening, a closure can be used to make the “_name” variable private. The Person constructor has been rewritten below using a closure. Note that “_name” is now a local variable of the Person constructor instead of an object property. A closure is formed because the outer function, Person() exposes an inner function by creating the public getName() method.

function Person(name) {

var _name = name;

this.getName = function() {

return _name;

};

}

Now, when getName() is called, it is guaranteed to return the value that was originally passed to the constructor. It is still possible for someone to add a new “_name” property to the object, but the internal workings of the object will not be affected as long as they refer to the variable bound by the closure. The following code shows that the “_name” variable is, indeed, private.

var person = new Person("Colin");

person._name = "Tom";

// person._name is "Tom" but person.getName() returns "Colin"

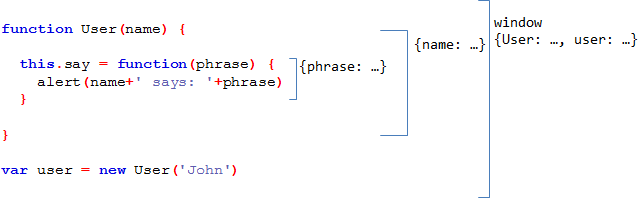

When Not to Use Closures

It is important to understand how closures work and when to use them.

It is equally important to understand when they are not the right tool

for the job at hand. Overusing closures can cause scripts to execute

slowly and consume unnecessary memory. And because closures are so

simple to create, it is possible to misuse them without even knowing

it. This section covers several scenarios where closures should be

used with caution.

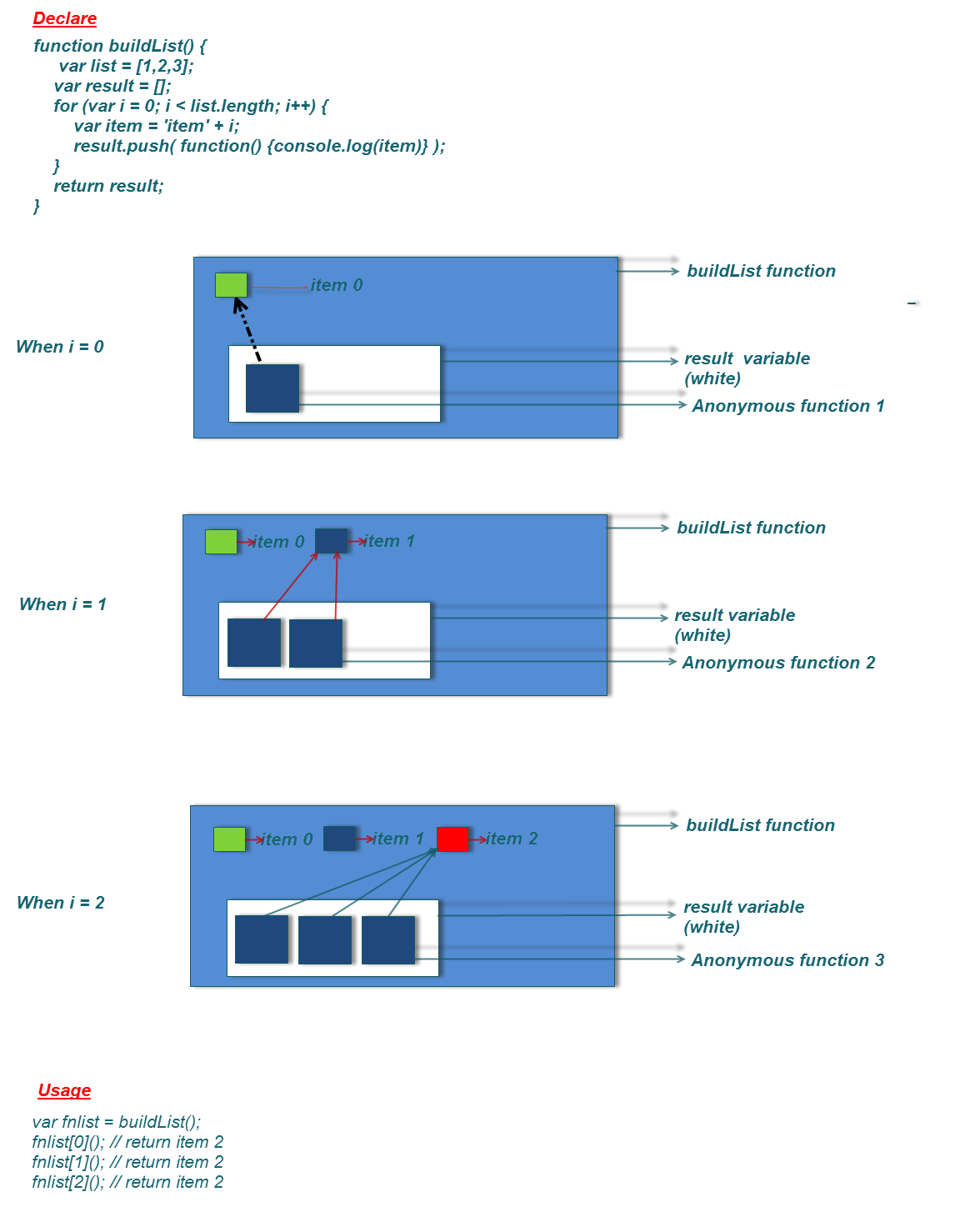

In Loops

Creating closures within loops can have misleading results. An example of this is shown below. In this example, three buttons are created. When “button1” is clicked, an alert should be displayed that says “Clicked button 1”. Similar messages should be shown for “button2” and “button3”. However, when this code is run, all of the buttons show “Clicked button 4”. This is because, by the time one of the buttons is clicked, the loop has finished executing, and the loop variable has reached its final value of four.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Closures</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<script>

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

for (var i = 1; i < 4; i++) {

var button = document.getElementById("button" + i);

button.addEventListener("click", function() {

alert("Clicked button " + i);

});

}

});

</script>

</head>

<body>

<input type="button" id="button1" value="One" />

<input type="button" id="button2" value="Two" />

<input type="button" id="button3" value="Three" />

</body>

</html>

To solve this problem, the closure must be decoupled from the actual loop variable. This can be done by calling a new function, which in turn creates a new referencing environment. The following example shows how this is done. The loop variable is passed to the getHandler() function. getHandler() then returns a closure that is independent of the original “for” loop.

function getHandler(i) {

return function handler() {

alert("Clicked button " + i);

};

}

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

for (var i = 1; i < 4; i++) {

var button = document.getElementById("button" + i);

button.addEventListener("click", getHandler(i));

}

});

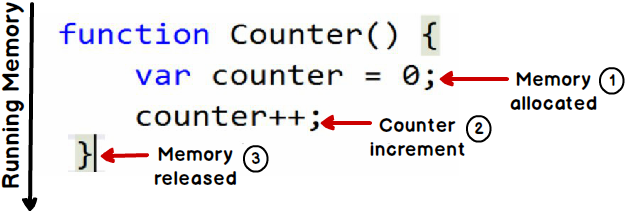

Unnecessary Use in Constructors

Constructor functions are another common source of closure misuse.

We’ve seen how closures can be used to emulate private data. However,

it is overkill to implement methods as closures if they don’t actually

access the private data. The following example revisits the Person

class, but this time adds a sayHello() method which doesn’t use the

private data.

function Person(name) {

var _name = name;

this.getName = function() {

return _name;

};

this.sayHello = function() {

alert("Hello!");

};

}

Each time a Person is instantiated, time is spent creating the

sayHello() method. If many Person objects are created, this becomes a

waste of time. A better approach would be to add sayHello() to the

Person prototype. By adding to the prototype, all Person objects can

share the same method. This saves time in the constructor by not

having to create a closure for each instance. The previous example is

rewritten below with the extraneous closure moved into the prototype.

function Person(name) {

var _name = name;

this.getName = function() {

return _name;

};

}

Person.prototype.sayHello = function() {

alert("Hello!");

};

Things to Remember

- Closures contain a function and a reference to the environment in

which the function was created.

- A closure is formed when an outer function exposes an inner function.

Closures can be used to easily pass parameters to callback functions.

- Private data can be emulated by using closures. This is common in

object-oriented programming and namespace design.

- Closures should be not overused in constructors. Adding to the

prototype is a better idea.

Link

curriedAdd(2)(3)()in your Functional Programming examples are besides when explaining closures or in coding interviews. I've done a lot of code reviews and have never come across it, but I've also never worked with computer science MVPs like I assume FANG companies employ. – Bikaner