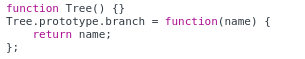

This is a very simple prototype based object model that would be considered as a sample during the explanation, with no comment yet:

function Person(name){

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.getName = function(){

console.log(this.name);

}

var person = new Person("George");

There are some crucial points that we have to consider before going through the prototype concept.

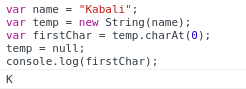

1- How JavaScript functions actually work:

To take the first step we have to figure out, how JavaScript functions actually work , as a class like function using this keyword in it or just as a regular function with its arguments, what it does and what it returns.

Let's say we want to create a Person object model. but in this step I'm gonna be trying to do the same exact thing without using prototype and new keyword.

So in this step functions, objects and this keyword, are all we have.

The first question would be how this keyword could be useful without using new keyword.

So to answer that let's say we have an empty object, and two functions like:

var person = {};

function Person(name){ this.name = name; }

function getName(){

console.log(this.name);

}

and now without using new keyword how we could use these functions. So JavaScript has 3 different ways to do that:

a. first way is just to call the function as a regular function:

Person("George");

getName();//would print the "George" in the console

in this case, this would be the current context object, which is usually is the global window object in the browser or GLOBAL in Node.js. It means we would have, window.name in browser or GLOBAL.name in Node.js, with "George" as its value.

b. We can attach them to an object, as its properties

-The easiest way to do this is modifying the empty person object, like:

person.Person = Person;

person.getName = getName;

this way we can call them like:

person.Person("George");

person.getName();// -->"George"

and now the person object is like:

Object {Person: function, getName: function, name: "George"}

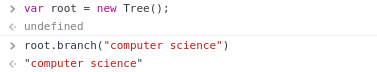

-The other way to attach a property to an object is using the prototype of that object that can be find in any JavaScript object with the name of __proto__, and I have tried to explain it a bit on the summary part. So we could get the similar result by doing:

person.__proto__.Person = Person;

person.__proto__.getName = getName;

But this way what we actually are doing is modifying the Object.prototype, because whenever we create a JavaScript object using literals ({ ... }), it gets created based on Object.prototype, which means it gets attached to the newly created object as an attribute named __proto__ , so if we change it, as we have done on our previous code snippet, all the JavaScript objects would get changed, not a good practice. So what could be the better practice now:

person.__proto__ = {

Person: Person,

getName: getName

};

and now other objects are in peace, but it still doesn't seem to be a good practice. So we have still one more solutions, but to use this solution we should get back to that line of code where person object got created (var person = {};) then change it like:

var propertiesObject = {

Person: Person,

getName: getName

};

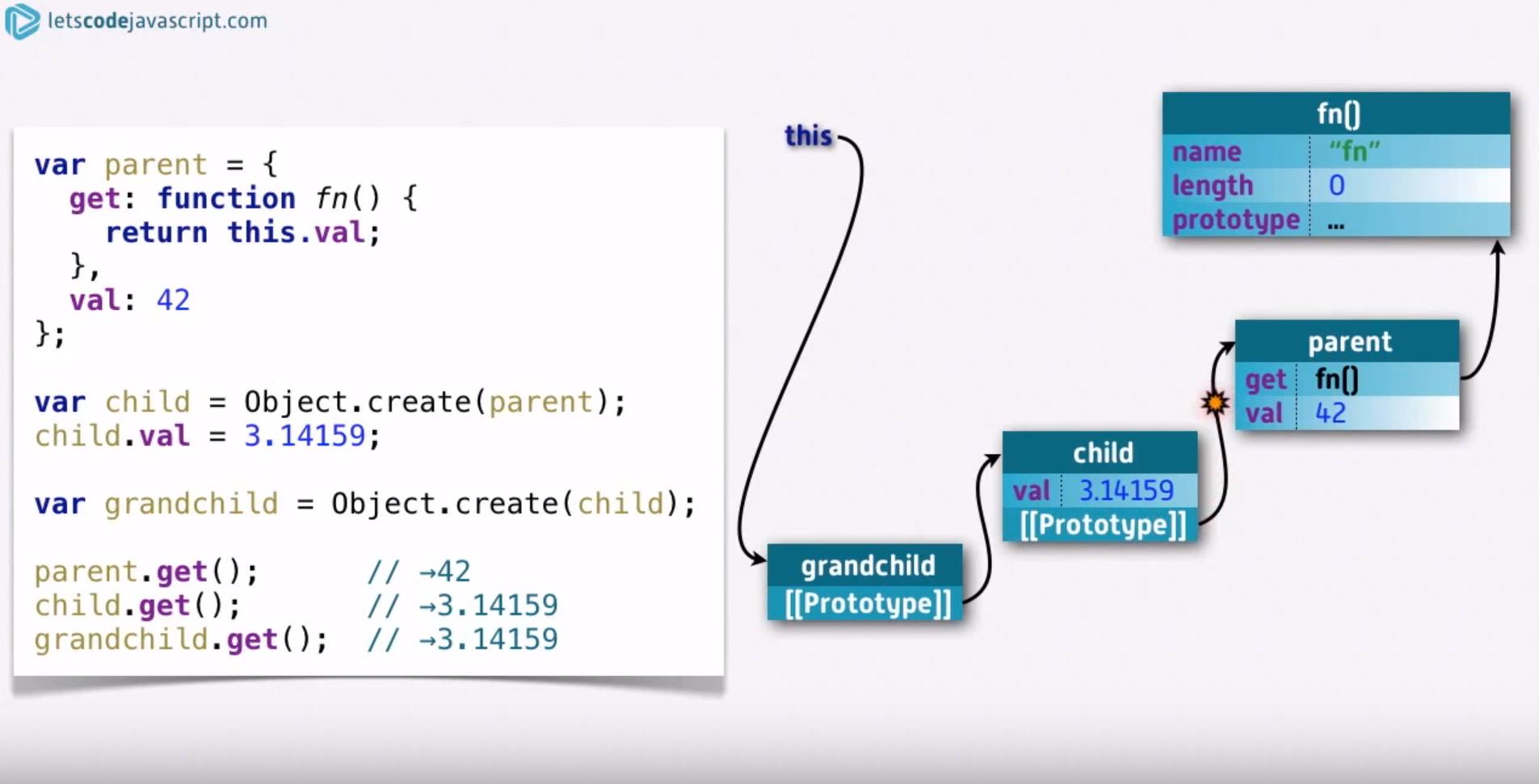

var person = Object.create(propertiesObject);

what it does is creating a new JavaScript Object and attach the propertiesObject to the __proto__ attribute. So to make sure you can do:

console.log(person.__proto__===propertiesObject); //true

But the tricky point here is you have access to all the properties defined in __proto__ on the first level of the person object(read the summary part for more detail).

as you see using any of these two way this would exactly point to the person object.

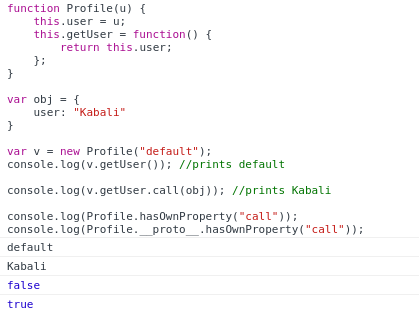

c. JavaScript has another way to provide the function with this, which is using call or apply to invoke the function.

The apply() method calls a function with a given this value and

arguments provided as an array (or an array-like object).

and

The call() method calls a function with a given this value and

arguments provided individually.

this way which is my favorite, we can easily call our functions like:

Person.call(person, "George");

or

//apply is more useful when params count is not fixed

Person.apply(person, ["George"]);

getName.call(person);

getName.apply(person);

these 3 methods are the important initial steps to figure out the .prototype functionality.

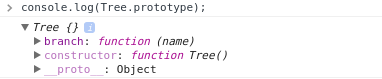

2- How does the new keyword work?

this is the second step to understand the .prototype functionality.this is what I use to simulate the process:

function Person(name){ this.name = name; }

my_person_prototype = { getName: function(){ console.log(this.name); } };

in this part I'm gonna be trying to take all the steps which JavaScript takes, without using the new keyword and prototype, when you use new keyword. so when we do new Person("George"), Person function serves as a constructor, These are what JavaScript does, one by one:

a. first of all it makes an empty object, basically an empty hash like:

var newObject = {};

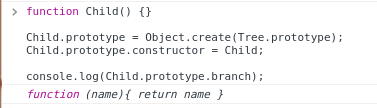

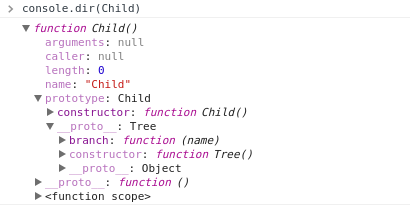

b. the next step that JavaScript takes is to attach the all prototype objects to the newly created object

we have my_person_prototype here similar to the prototype object.

for(var key in my_person_prototype){

newObject[key] = my_person_prototype[key];

}

It is not the way that JavaScript actually attaches the properties that are defined in the prototype. The actual way is related to the prototype chain concept.

a. & b. Instead of these two steps you can have the exact same result by doing:

var newObject = Object.create(my_person_prototype);

//here you can check out the __proto__ attribute

console.log(newObject.__proto__ === my_person_prototype); //true

//and also check if you have access to your desired properties

console.log(typeof newObject.getName);//"function"

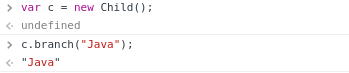

now we can call the getName function in our my_person_prototype:

newObject.getName();

c. then it gives that object to the constructor,

we can do this with our sample like:

Person.call(newObject, "George");

or

Person.apply(newObject, ["George"]);

then the constructor can do whatever it wants, because this inside of that constructor is the object that was just created.

now the end result before simulating the other steps:

Object {name: "George"}

Summary:

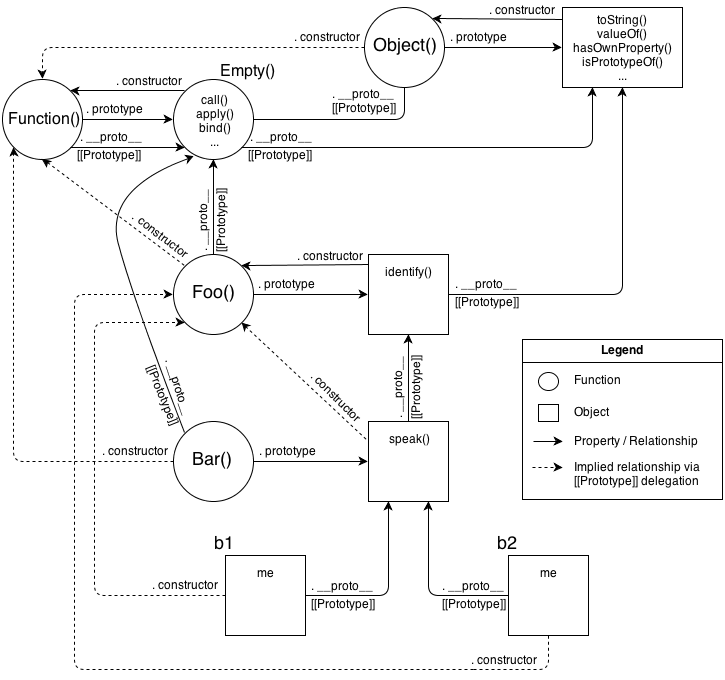

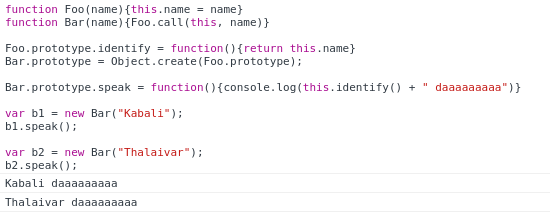

Basically, when you use the new keyword on a function, you are calling on that and that function serves as a constructor, so when you say:

new FunctionName()

JavaScript internally makes an object, an empty hash and then it gives that object to the constructor, then the constructor can do whatever it wants, because this inside of that constructor is the object that was just created and then it gives you that object of course if you haven't used the return statement in your function or if you've put a return undefined; at the end of your function body.

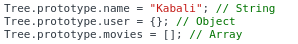

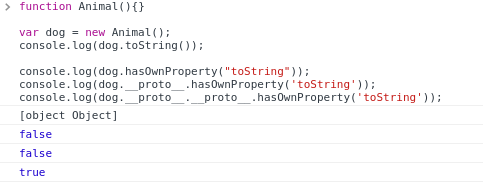

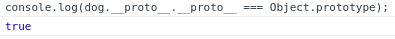

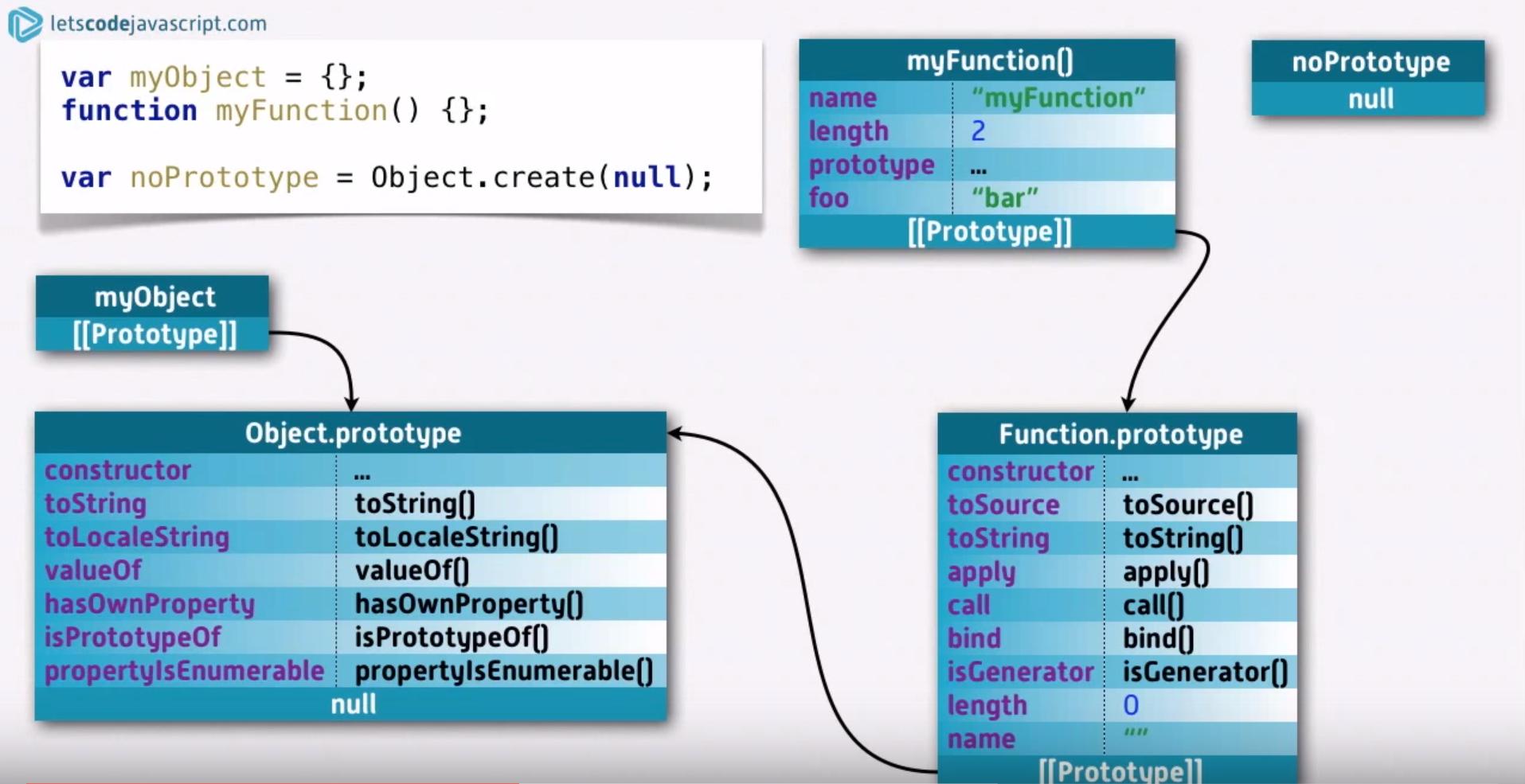

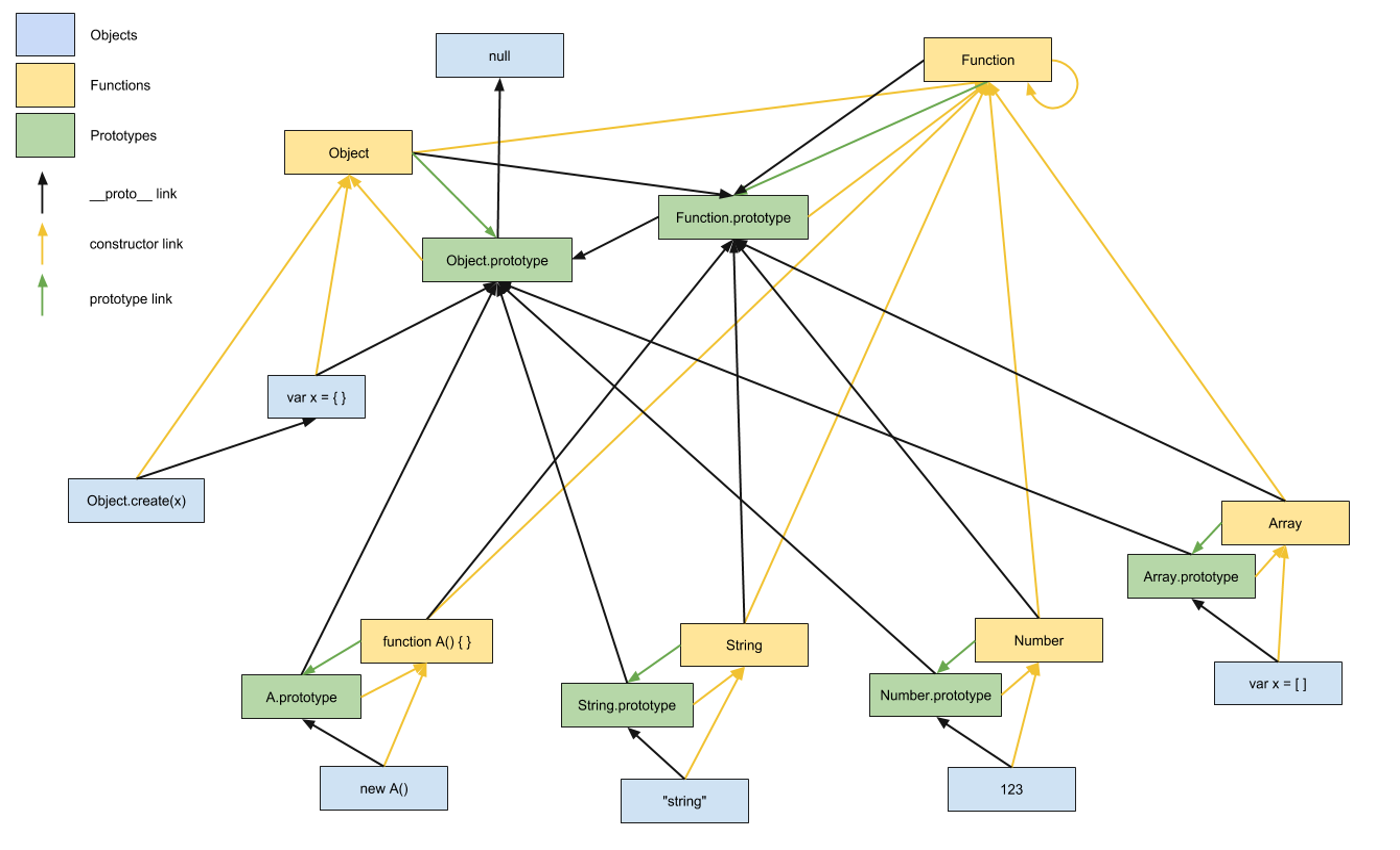

So when JavaScript goes to look up a property on an object, the first thing it does, is it looks it up on that object. And then there is a secret property [[prototype]] which we usually have it like __proto__ and that property is what JavaScript looks at next. And when it looks through the __proto__, as far as it is again another JavaScript object, it has its own __proto__ attribute, it goes up and up until it gets to the point where the next __proto__ is null. The point is the only object in JavaScript that its __proto__ attribute is null is Object.prototype object:

console.log(Object.prototype.__proto__===null);//true

and that's how inheritance works in JavaScript.

![The prototype chain]()

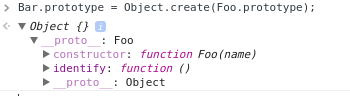

In other words, when you have a prototype property on a function and you call a new on that, after JavaScript finishes looking at that newly created object for properties, it will go look at the function's .prototype and also it is possible that this object has its own internal prototype. and so on.

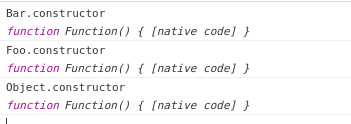

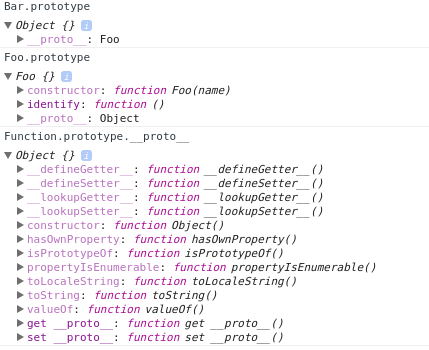

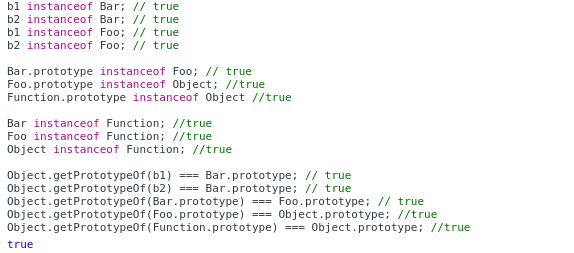

![*[[protytype]]* and <code>prototype</code> property of function objects](https://static.mcmap.net/file/mcmap/ZG-AbGLDKwfpKnMAWVMrKmltX1ywKmMva3/rcGmc.png)