Bit late to the party, but I was exploring this issue today and noticed that many of the answers don't completely address how Javascript treats scopes, which is essentially what this boils down to.

So as many others mentioned, the problem is that the inner function is referencing the same i variable. So why don't we just create a new local variable each iteration, and have the inner function reference that instead?

//overwrite console.log() so you can see the console output

console.log = function(msg) {document.body.innerHTML += '<p>' + msg + '</p>';};

var funcs = {};

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

var ilocal = i; //create a new local variable

funcs[i] = function() {

console.log("My value: " + ilocal); //each should reference its own local variable

};

}

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

funcs[j]();

}

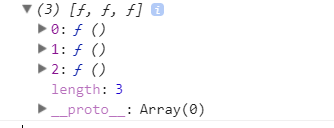

Just like before, where each inner function outputted the last value assigned to i, now each inner function just outputs the last value assigned to ilocal. But shouldn't each iteration have it's own ilocal?

Turns out, that's the issue. Each iteration is sharing the same scope, so every iteration after the first is just overwriting ilocal. From MDN:

Important: JavaScript does not have block scope. Variables introduced with a block are scoped to the containing function or script, and the effects of setting them persist beyond the block itself. In other words, block statements do not introduce a scope. Although "standalone" blocks are valid syntax, you do not want to use standalone blocks in JavaScript, because they don't do what you think they do, if you think they do anything like such blocks in C or Java.

Reiterated for emphasis:

JavaScript does not have block scope. Variables introduced with a block are scoped to the containing function or script

We can see this by checking ilocal before we declare it in each iteration:

//overwrite console.log() so you can see the console output

console.log = function(msg) {document.body.innerHTML += '<p>' + msg + '</p>';};

var funcs = {};

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

console.log(ilocal);

var ilocal = i;

}

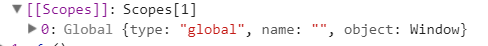

This is exactly why this bug is so tricky. Even though you are redeclaring a variable, Javascript won't throw an error, and JSLint won't even throw a warning. This is also why the best way to solve this is to take advantage of closures, which is essentially the idea that in Javascript, inner functions have access to outer variables because inner scopes "enclose" outer scopes.

![Closures]()

This also means that inner functions "hold onto" outer variables and keep them alive, even if the outer function returns. To utilize this, we create and call a wrapper function purely to make a new scope, declare ilocal in the new scope, and return an inner function that uses ilocal (more explanation below):

//overwrite console.log() so you can see the console output

console.log = function(msg) {document.body.innerHTML += '<p>' + msg + '</p>';};

var funcs = {};

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

funcs[i] = (function() { //create a new scope using a wrapper function

var ilocal = i; //capture i into a local var

return function() { //return the inner function

console.log("My value: " + ilocal);

};

})(); //remember to run the wrapper function

}

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

funcs[j]();

}

Creating the inner function inside a wrapper function gives the inner function a private environment that only it can access, a "closure". Thus, every time we call the wrapper function we create a new inner function with it's own separate environment, ensuring that the ilocal variables don't collide and overwrite each other. A few minor optimizations gives the final answer that many other SO users gave:

//overwrite console.log() so you can see the console output

console.log = function(msg) {document.body.innerHTML += '<p>' + msg + '</p>';};

var funcs = {};

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

funcs[i] = wrapper(i);

}

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

funcs[j]();

}

//creates a separate environment for the inner function

function wrapper(ilocal) {

return function() { //return the inner function

console.log("My value: " + ilocal);

};

}

Update

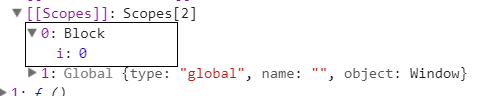

With ES6 now mainstream, we can now use the new let keyword to create block-scoped variables:

//overwrite console.log() so you can see the console output

console.log = function(msg) {document.body.innerHTML += '<p>' + msg + '</p>';};

var funcs = {};

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) { // use "let" to declare "i"

funcs[i] = function() {

console.log("My value: " + i); //each should reference its own local variable

};

}

for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) { // we can use "var" here without issue

funcs[j]();

}

Look how easy it is now! For more information see this answer, which my info is based off of.

iin the global scope. That's JS : )letinstead ofvarsolves this by creating a new scope each time the loop runs, creating a separated scope for each function to close over. Various other techniques do the same thing with extra functions. – Mayst