Suppose I want to uniformly sample points inside a convex polygon.

One of the most common approaches described here and on the internet in general consists in triangulation of the polygon and generate uniformly random points inside each triangles using different schemes.

The one I find most practical is to generate exponential distributions from uniform ones taking -log(U) for instance and normalizing the sum to one.

Within Matlab, we would have this code to sample uniformly inside a triangle:

vertex=[0 0;1 0;0.5 0.5]; %vertex coordinates in the 2D plane

mix_coeff=rand(10000,size(vertex,1)); %uniform generation of random coefficients

x=-log(x); %make the uniform distribution exponential

x=bsxfun(@rdivide,x,sum(x,2)); %normalize such that sum is equal to one

unif_samples=x*vertex; %calculate the 2D coordinates of each sample inside the triangle

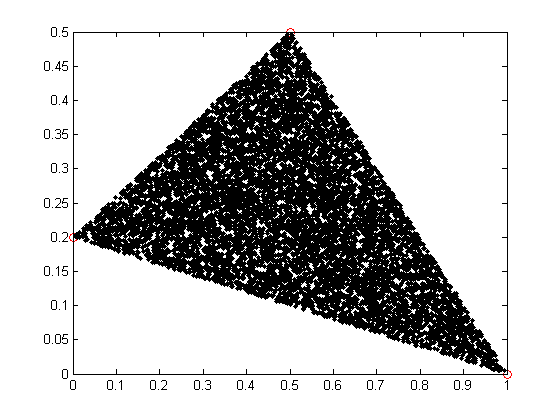

And this works just fine:

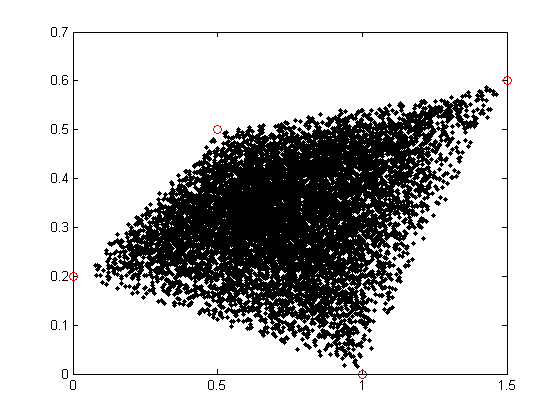

However, using the exact same scheme for anything other than a triangle just fails. For instance for a quadrilateral, we get the following result:

Clearly, sampling is not uniform anymore and the more vertices you add, the more difficult it is to "reach" the corners.

If I triangulate the polygon first then uniform sampling in each triangle is easy and obviously gets the job done.

But why? Why is it necessary to triangulate first?

Which specific property have triangle (and simplexes in general since this behaviour seems to extend to n-dimensional constructions) that makes it work for them and not for the other polygons?

I would be grateful if someone could give me an intuitive explanation of the phenomena or just point to some reference that could help me understand what is going on.