The Git book contains an article on what an index includes:

The index is a binary file (generally kept in .git/index) containing a sorted list of path names, each with permissions and the SHA1 of a blob object; git ls-files can show you the contents of the index:

$ git ls-files --stage

100644 63c918c667fa005ff12ad89437f2fdc80926e21c 0 .gitignore

100644 5529b198e8d14decbe4ad99db3f7fb632de0439d 0 .mailmap

The Racy git problem gives some more details on that structure:

The index is one of the most important data structures in git.

It represents a virtual working tree state by recording list of paths and their object names and serves as a staging area to write out the next tree object to be committed.

The state is "virtual" in the sense that it does not necessarily have to, and often does not, match the files in the working tree.

Nov. 2021: see also "Make your monorepo feel small with Git’s sparse index" from Derrick Stolee (Microsoft/GitHub)

![https://static.mcmap.net/file/mcmap/ZG-AbGLDKwfnZ7-ocV9QWmYvXe/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fig-1-working-directory-index-commit-history.png]()

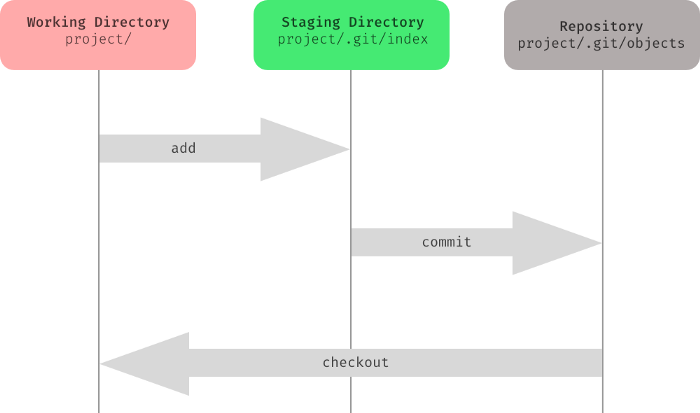

The Git index is a critical data structure in Git. It serves as the “staging area” between the files you have on your filesystem and your commit history.

- When you run

git add, the files from your working directory are hashed and stored as objects in the index, leading them to be “staged changes”.

- When you run

git commit, the staged changes as stored in the index are used to create that new commit.

- When you run

git checkout, Git takes the data from a commit and writes it to the working directory and the index.

In addition to storing your staged changes, the index also stores filesystem information about your working directory.

This helps Git report changed files more quickly.

To see more, cf. "git/git/blob/master/Documentation/gitformat-index.txt":

The Git index file has the following format

All binary numbers are in network byte order.

Version 2 is described here unless stated otherwise.

- A 12-byte header consisting of:

- 4-byte signature:

The signature is { 'D', 'I', 'R', 'C' } (stands for "dircache")

- 4-byte version number:

The current supported versions are 2, 3 and 4.

- 32-bit number of index entries.

- A number of sorted index entries.

- Extensions:

Extensions are identified by signature.

Optional extensions can be ignored if Git does not understand them.

Git currently supports cached tree and resolve undo extensions.

- 4-byte extension signature. If the first byte is '

A'..'Z' the extension is optional and can be ignored.

- 32-bit size of the extension

- Extension data

- 160-bit SHA-1 over the content of the index file before this checksum.

mljrg comments:

If the index is the place where the next commit is prepared, why doesn't "git ls-files -s" return nothing after commit?

Because the index represents what is being tracked, and right after a commit, what is being tracked is identical to the last commit (git diff --cached returns nothing).

So git ls-files -s lists all files tracked (object name, mode bits and stage number in the output).

That list (of element tracked) is initialized with the content of a commit.

When you switch branch, the index content is reset to the commit referenced by the branch you just switched to.

Git 2.20 (Q4 2018) adds an Index Entry Offset Table (IEOT):

See commit 77ff112, commit 3255089, commit abb4bb8, commit c780b9c, commit 3b1d9e0, commit 371ed0d (10 Oct 2018) by Ben Peart (benpeart).

See commit 252d079 (26 Sep 2018) by Nguyễn Thái Ngọc Duy (pclouds).

(Merged by Junio C Hamano -- gitster -- in commit e27bfaa, 19 Oct 2018)

ieot: add Index Entry Offset Table (IEOT) extension

This patch enables addressing the CPU cost of loading the index by adding

additional data to the index that will allow us to efficiently multi-

thread the loading and conversion of cache entries.

It accomplishes this by adding an (optional) index extension that is a

table of offsets to blocks of cache entries in the index file.

To make this work for V4 indexes, when writing the cache entries, it periodically"resets" the prefix-compression by encoding the current entry as if the path name for the previous entry is completely different and saves the

offset of that entry in the IEOT.

Basically, with V4 indexes, it generates offsets into blocks of prefix-compressed entries.

With the new index.threads config setting, the index loading is now faster.

As a result (of using IEOT), commit 7bd9631 clean-up the read-cache.c load_cache_entries_threaded() function for Git 2.23 (Q3 2019).

See commit 8373037, commit d713e88, commit d92349d, commit 113c29a, commit c95fc72, commit 7a2a721, commit c016579, commit be27fb7, commit 13a1781, commit 7bd9631, commit 3c1dce8, commit cf7a901, commit d64db5b, commit 76a7bc0 (09 May 2019) by Jeff King (peff).

(Merged by Junio C Hamano -- gitster -- in commit c0e78f7, 13 Jun 2019)

read-cache: drop unused parameter from threaded load

The load_cache_entries_threaded() function takes a src_offset parameter

that it doesn't use. This has been there since its inception in 77ff112 (read-cache: load cache entries on worker threads, 2018-10-10, Git v2.20.0-rc0).

Digging on the mailing list, that parameter was part of an earlier iteration of the series, but became unnecessary when the code switched to using the IEOT extension.

With Git 2.29 (Q4 2020), the format description adjusts to the recent SHA-256 work.

See commit 8afa50a, commit 0756e61, commit 123712b, commit 5b6422a (15 Aug 2020) by Martin Ågren (none).

(Merged by Junio C Hamano -- gitster -- in commit 74a395c, 19 Aug 2020)

Signed-off-by: Martin Ågren

Document that in SHA-1 repositories, we use SHA-1 and in SHA-256 repositories, we use SHA-256, then replace all other uses of "SHA-1" with something more neutral.

Avoid referring to "160-bit" hash values.

technical/index-format now includes in its man page:

All binary numbers are in network byte order.

In a repository using the traditional SHA-1, checksums and object IDs

(object names) mentioned below are all computed using SHA-1.

Similarly, in SHA-256 repositories, these values are computed using SHA-256.

Version 2 is described here unless stated otherwise.

Commit 4950aca from commit cf4a3bd, Git 2.44, Q1 2024, details the block management in a Git index.