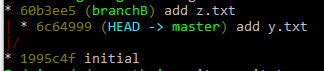

It is not entirely clear what your desired outcome is, so there is some confusion about the "correct" way of doing it in the answers and their comments. I try to give an overview and see the following three options:

Try merge and use B for conflicts

This is not the "theirs version for git merge -s ours" but the "theirs version for git merge -X ours" (which is short for git merge -s recursive -X ours):

git checkout branchA

# also uses -s recursive implicitly

git merge -X theirs branchB

This is what e.g. Alan W. Smith's answer does.

Use content from B only

This creates a merge commit for both branches but discards all changes from branchA and only keeps the contents from branchB.

# Get the content you want to keep.

# If you want to keep branchB at the current commit, you can add --detached,

# else it will be advanced to the merge commit in the next step.

git checkout branchB

# Do the merge an keep current (our) content from branchB we just checked out.

git merge -s ours branchA

# Set branchA to current commit and check it out.

git checkout -B branchA

Note that the merge commits first parent now is that from branchB and only the second is from branchA. This is what e.g. Gandalf458's answer does.

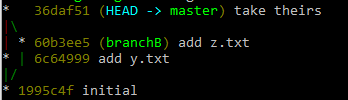

Use content from B only and keep correct parent order

This is the real "theirs version for git merge -s ours". It has the same content as in the option before (i.e. only that from branchB) but the order of parents is correct, i.e. the first parent comes from branchA and the second from branchB.

git checkout branchA

# Do a merge commit. The content of this commit does not matter,

# so use a strategy that never fails.

# Note: This advances branchA.

git merge -s ours branchB

# Change working tree and index to desired content.

# --detach ensures branchB will not move when doing the reset in the next step.

git checkout --detach branchB

# Move HEAD to branchA without changing contents of working tree and index.

git reset --soft branchA

# 'attach' HEAD to branchA.

# This ensures branchA will move when doing 'commit --amend'.

git checkout branchA

# Change content of merge commit to current index (i.e. content of branchB).

git commit --amend -C HEAD

This is what Paul Pladijs's answer does (without requiring a temporary branch).

Special cases

If the commit of branchB is an ancestor of branchA, git merge does not work (it just exits with a message like "Already up to date.").

In this or other similar/advanced cases the low-level command git commit-tree can be used.

git merge -s their. – Meitgit merge -s theirs(that can be achieved easily withgit merge -s oursand a temporary branch), since -s ours completely ignores the changes of the merge-from branch... – Portraituretheirsin addition toours??? This is a symptom of one of the high level engineering and design problems in Git: inconsistency. – Blondgit merge -s ours. – Featherveinedgit merge -X theirs– Jurgen-s oursbefore merging your branch on master. Maybe consider changing accepted answer as certain people find it inaccurate. – Soredium