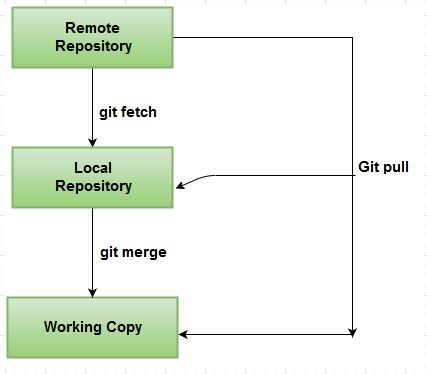

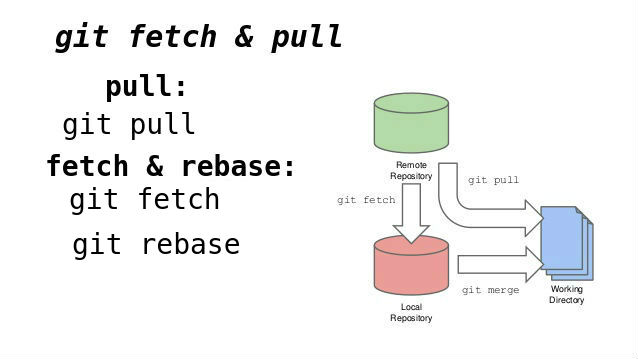

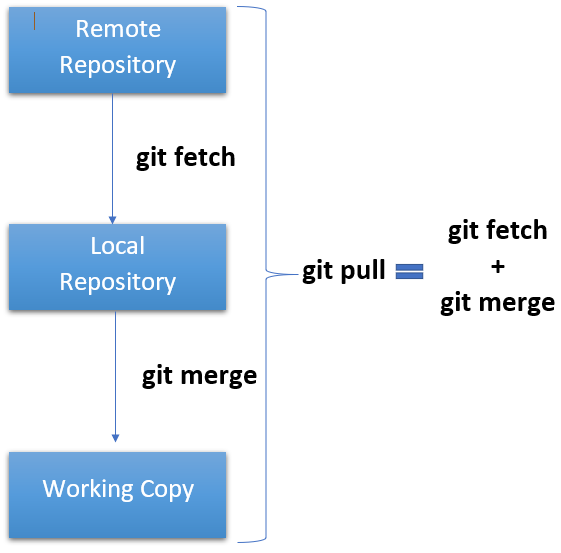

In the simplest terms, git pull does a git fetch followed by a git merge.

git fetch updates your remote-tracking branches under refs/remotes/<remote>/. This operation is safe to run at any time since it never changes any of your local branches under refs/heads.

git pull brings a local branch up-to-date with its remote version, while also updating your other remote-tracking branches.

From the Git documentation for git pull:

git pullrunsgit fetchwith the given parameters and then depending on configuration options or command line flags, will call eithergit rebaseorgit mergeto reconcile diverging branches.

git pull will always merge into the current branch. So you select which branch you want to pull from, and it pulls it into the current branch. The from branch can be local or remote; it can even be a remote branch that's not a registered git remote (meaning you pass a URL on the git pull command line). –

Acrodrome /home/alice/ and do git fetch /home/bob, what parameters should I pass to the subsequent git merge ? –

Garrulity pull can't actually be emulated by a fetch plus a merge. I just fetched a change where only a remote branch pointer changes, and merge refuses to do anything. pull, on the other hand, fast-forwards my tracking branch. –

Slype git fetch something like staging FROM the remote repository? (I'm somewhat new to version control and Git) –

Elsyelton git fetch mission is to update all your branches, where git pull focuses more on the current branch –

Ratchford git fetch in a cron job? What's wrong with that? –

Ratchford git pulltries to automatically merge after fetching commits. It is context sensitive, so all pulled commits will be merged into your currently active branch.git pullautomatically merges the commits without letting you review them first. If you don’t carefully manage your branches, you may run into frequent conflicts.git fetchgathers any commits from the target branch that do not exist in the current branch and stores them in your local repository. However, it does not merge them with your current branch. This is particularly useful if you need to keep your repository up to date, but are working on something that might break if you update your files. To integrate the commits into your current branch, you must usegit mergeafterwards.

git fetch only updates your .git/ directory (AKA: local repository) and nothing outside .git/ (AKA: working tree). It does not change your local branches, and it does not touch master either. It touches remotes/origin/master though (see git branch -avv). If you have more remotes, try git remote update. This is a git fetch for all remotes in one command. –

Irremediable .git/refs/remotes/origin/. –

Typhoon fetch command is something like a "commit from the remote to local". Right? –

Elsyelton It is important to contrast the design philosophy of git with the philosophy of a more traditional source control tool like SVN.

Subversion was designed and built with a client/server model. There is a single repository that is the server, and several clients can fetch code from the server, work on it, then commit it back to the server. The assumption is that the client can always contact the server when it needs to perform an operation.

Git was designed to support a more distributed model with no need for a central repository (though you can certainly use one if you like). Also git was designed so that the client and the "server" don't need to be online at the same time. Git was designed so that people on an unreliable link could exchange code via email, even. It is possible to work completely disconnected and burn a CD to exchange code via git.

In order to support this model git maintains a local repository with your code and also an additional local repository that mirrors the state of the remote repository. By keeping a copy of the remote repository locally, git can figure out the changes needed even when the remote repository is not reachable. Later when you need to send the changes to someone else, git can transfer them as a set of changes from a point in time known to the remote repository.

git fetchis the command that says "bring my local copy of the remote repository up to date."git pullsays "bring the changes in the remote repository to where I keep my own code."

Normally git pull does this by doing a git fetch to bring the local copy of the remote repository up to date, and then merging the changes into your own code repository and possibly your working copy.

The take away is to keep in mind that there are often at least three copies of a project on your workstation. One copy is your own repository with your own commit history. The second copy is your working copy where you are editing and building. The third copy is your local "cached" copy of a remote repository.

remoteName/ Git from the ground up is a very good read. Once you get an understanding of how Git works - and it's beautifully simple, really - everything just makes sense. –

Spherics git clone and git merge would be very helpful! –

Merline git merge - it should clearly show that merge called separately is NOT the same as calling pull because pull is merging from remote only and ignores your local commits in your local branch which is tracking the remote branch being pulled from. –

Tael merge in the diagram because it currently has pull only. I've seen pull confusing quite a few beginners because they tend to assume that pull is a magic command to refresh all the local copies of the remote branches and are surprised when they later switch to another branch and discover that it was not updated by the recent pull. –

Tael One use case of git fetch is that the following will tell you any changes in the remote branch since your last pull... so you can check before doing an actual pull, which could change files in your current branch and working copy.

git fetch

git diff ...origin

See git diff documentation regarding the double- .. and triple-dot ... syntax.

fetch can't have conflicts by definition. It merely fetches changes from the remote. Conflicts occur when we merge changes –

Anagoge It cost me a little bit to understand what was the difference, but this is a simple explanation. master in your localhost is a branch.

When you clone a repository you fetch the entire repository to you local host. This means that at that time you have an origin/master pointer to HEAD and master pointing to the same HEAD.

when you start working and do commits you advance the master pointer to HEAD + your commits. But the origin/master pointer is still pointing to what it was when you cloned.

So the difference will be:

- If you do a

git fetchit will just fetch all the changes in the remote repository (GitHub) and move the origin/master pointer toHEAD. Meanwhile your local branch master will keep pointing to where it has. - If you do a

git pull, it will do basically fetch (as explained previously) and merge any new changes to your master branch and move the pointer toHEAD.

Even more briefly

git fetch fetches updates but does not merge them.

git pull does a git fetch under the hood and then a merge.

Briefly

git fetch is similar to pull but doesn't merge. i.e. it fetches remote updates (refs and objects) but your local stays the same (i.e. origin/master gets updated but master stays the same) .

git pull pulls down from a remote and instantly merges.

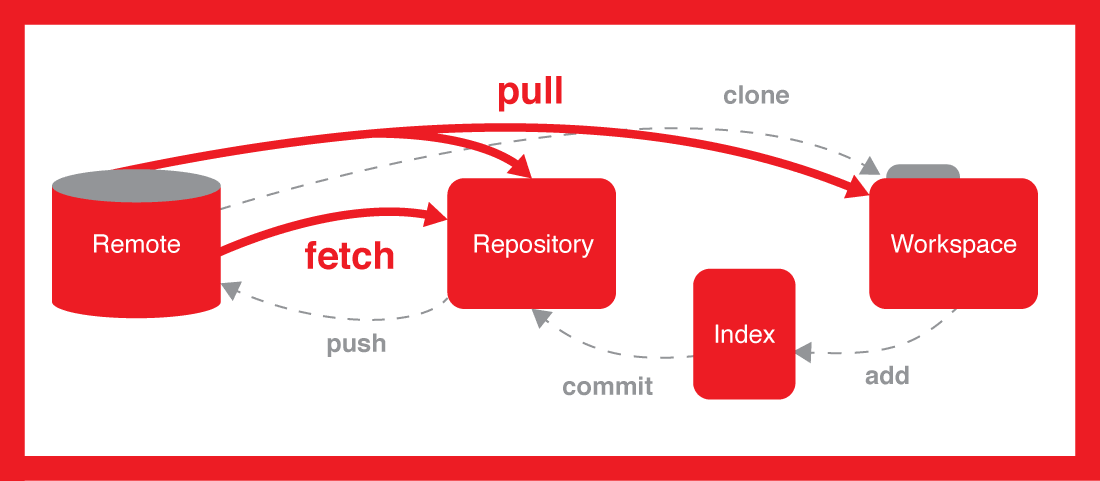

More

git clone clones a repo.

git rebase saves stuff from your current branch that isn't in the upstream branch to a temporary area. Your branch is now the same as before you started your changes. So, git pull -rebase will pull down the remote changes, rewind your local branch, replay your changes over the top of your current branch one by one until you're up-to-date.

Also, git branch -a will show you exactly what’s going on with all your branches - local and remote.

This blog post was useful:

The difference between git pull, git fetch and git clone (and git rebase) - Mike Pearce

and covers git pull, git fetch, git clone and git rebase.

UPDATE

I thought I'd update this to show how you'd actually use this in practice.

Update your local repo from the remote (but don't merge):

git fetchAfter downloading the updates, let's see the differences:

git diff master origin/masterIf you're happy with those updates, then merge:

git pull

Notes:

On step 2: For more on diffs between local and remotes, see: How to compare a local Git branch with its remote branch

On step 3: It's probably more accurate (e.g. on a fast changing repo) to do a git rebase origin here. See @Justin Ohms comment in another answer.

See also: http://longair.net/blog/2009/04/16/git-fetch-and-merge/

Note also: I've mentioned a merge during a pull however you can configure a pull to use a rebase instead.

git merge instead of git pull, since git fetch already happened? –

Marielamariele git-pull - Fetch from and merge with another repository or a local branch SYNOPSIS git pull … DESCRIPTION Runs git-fetch with the given parameters, and calls git-merge to merge the retrieved head(s) into the current branch. With --rebase, calls git-rebase instead of git-merge. Note that you can use . (current directory) as the <repository> to pull from the local repository — this is useful when merging local branches into the current branch. Also note that options meant for git-pull itself and underlying git-merge must be given before the options meant for git-fetch.

You would pull if you want the histories merged, you'd fetch if you just 'want the codez' as some person has been tagging some articles around here.

OK, here is some information about git pull and git fetch, so you can understand the actual differences... in few simple words, fetch gets the latest data, but not the code changes and not going to mess with your current local branch code, but pull get the code changes and merge it your local branch straight away, read on to get more details about each:

git fetch

It will download all refs and objects and any new branches to your local Repository...

Fetch branches and/or tags (collectively, "refs") from one or more other repositories, along with the objects necessary to complete their histories. Remote-tracking branches are updated (see the description of below for ways to control this behavior).

By default, any tag that points into the histories being fetched is also fetched; the effect is to fetch tags that point at branches that you are interested in. This default behavior can be changed by using the --tags or --no-tags options or by configuring remote..tagOpt. By using a refspec that fetches tags explicitly, you can fetch tags that do not point into branches you are interested in as well.

git fetch can fetch from either a single named repository or URL or from several repositories at once if is given and there is a remotes. entry in the configuration file. (See git-config1).

When no remote is specified, by default the origin remote will be used, unless there’s an upstream branch configured for the current branch.

The names of refs that are fetched, together with the object names they point at, are written to .git/FETCH_HEAD. This information may be used by scripts or other git commands, such as git-pull.

git pull

It will apply the changes from remote to the current branch in local...

Incorporates changes from a remote repository into the current branch. In its default mode, git pull is shorthand for git fetch followed by git merge FETCH_HEAD.

More precisely, git pull runs git fetch with the given parameters and calls git merge to merge the retrieved branch heads into the current branch. With --rebase, it runs git rebase instead of git merge.

should be the name of a remote repository as passed to git-fetch1. can name an arbitrary remote ref (for example, the name of a tag) or even a collection of refs with corresponding remote-tracking branches (e.g., refs/heads/:refs/remotes/origin/), but usually it is the name of a branch in the remote repository.

Default values for and are read from the "remote" and "merge" configuration for the current branch as set by git-branch --track.

I also create the visual below to show you how git fetch and git pull working together...

The short and easy answer is that git pull is simply git fetch followed by git merge.

It is very important to note that git pull will automatically merge whether you like it or not. This could, of course, result in merge conflicts. Let's say your remote is origin and your branch is master. If you git diff origin/master before pulling, you should have some idea of potential merge conflicts and could prepare your local branch accordingly.

In addition to pulling and pushing, some workflows involve git rebase, such as this one, which I paraphrase from the linked article:

git pull origin master

git checkout foo-branch

git rebase master

git push origin foo-branch

If you find yourself in such a situation, you may be tempted to git pull --rebase. Unless you really, really know what you are doing, I would advise against that. This warning is from the man page for git-pull, version 2.3.5:

This is a potentially dangerous mode of operation. It rewrites history, which does not bode well when you published that history already. Do not use this option unless you have read git-rebase(1) carefully.

You can fetch from a remote repository, see the differences and then pull or merge.

This is an example for a remote repository called origin and a branch called master tracking the remote branch origin/master:

git checkout master

git fetch

git diff origin/master

git rebase origin master

This interactive graphical representation is very helpful in understanging git: http://ndpsoftware.com/git-cheatsheet.html

git fetch just "downloads" the changes from the remote to your local repository. git pull downloads the changes and merges them into your current branch. "In its default mode, git pull is shorthand for git fetch followed by git merge FETCH_HEAD."

Bonus:

In speaking of pull & fetch in the above answers, I would like to share an interesting trick,

git pull --rebase

This above command is the most useful command in my git life which saved a lots of time.

Before pushing your new commits to server, try this command and it will automatically sync latest server changes (with a fetch + merge) and will place your commit at the top in git log. No need to worry about manual pull/merge.

Find details at: http://gitolite.com/git-pull--rebase

I like to have some visual representation of the situation to grasp these things. Maybe other developers would like to see it too, so here's my addition. I'm not totally sure that it all is correct, so please comment if you find any mistakes.

LOCAL SYSTEM

. =====================================================

================= . ================= =================== =============

REMOTE REPOSITORY . REMOTE REPOSITORY LOCAL REPOSITORY WORKING COPY

(ORIGIN) . (CACHED)

for example, . mirror of the

a github repo. . remote repo

Can also be .

multiple repo's .

.

.

FETCH *------------------>*

Your local cache of the remote is updated with the origin (or multiple

external sources, that is git's distributed nature)

.

PULL *-------------------------------------------------------->*

changes are merged directly into your local copy. when conflicts occur,

you are asked for decisions.

.

COMMIT . *<---------------*

When coming from, for example, subversion, you might think that a commit

will update the origin. In git, a commit is only done to your local repo.

.

PUSH *<---------------------------------------*

Synchronizes your changes back into the origin.

Some major advantages for having a fetched mirror of the remote are:

- Performance (scroll through all commits and messages without trying to squeeze it through the network)

- Feedback about the state of your local repo (for example, I use Atlassian's SourceTree, which will give me a bulb indicating if I'm commits ahead or behind compared to the origin. This information can be updated with a GIT FETCH).

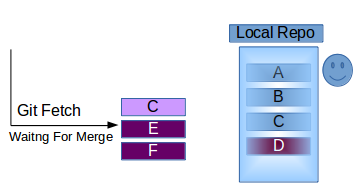

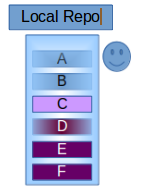

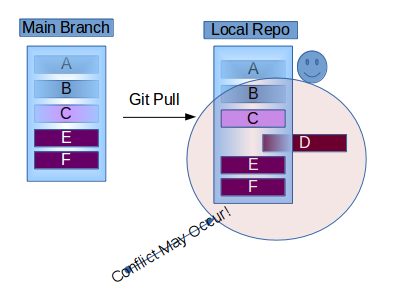

The Difference between GIT Fetch and GIT Pull can be explained with the following scenario: (Keeping in mind that pictures speak louder than words!, I have provided pictorial representation)

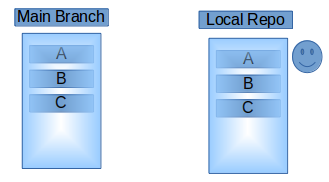

Let's take an example that you are working on a project with your team members. So there will be one main Branch of the project and all the contributors must fork it to their own local repository and then work on this local branch to modify/Add modules then push back to the main branch.

So,

Initial State of the two Branches when you forked the main project on your local repository will be like this- (A, B and C are Modules already completed of the project)

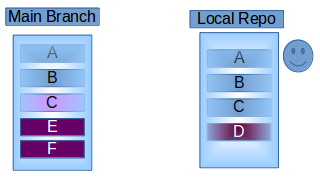

Now, you have started working on the new module (suppose D) and when you have completed the D module you want to push it to the main branch, But meanwhile what happens is that one of your teammates has developed new Module E, F and modified C.

So now what has happened is that your local repository is lacking behind the original progress of the project and thus pushing of your changes to the main branch can lead to conflict and may cause your Module D to malfunction.

To avoid such issues and to work parallel with the original progress of the project there are Two ways:

1. Git Fetch- This will Download all the changes that have been made to the origin/main branch project which are not present in your local branch. And will wait for the Git Merge command to apply the changes that have been fetched to your Repository or branch.

So now You can carefully monitor the files before merging it to your repository. And you can also modify D if required because of Modified C.

2. Git Pull- This will update your local branch with the origin/main branch i.e. actually what it does is a combination of Git Fetch and Git merge one after another. But this may Cause Conflicts to occur, so it’s recommended to use Git Pull with a clean copy.

I have struggled with this as well. In fact I got here with a google search of exactly the same question. Reading all these answers finally painted a picture in my head and I decided to try to get this down looking at the state of the 2 repositories and 1 sandbox and actions performed over time while watching the version of them. So here is what I came up with. Please correct me if I messed up anywhere.

The three repos with a fetch:

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Remote Repo - - Remote Repo - - Remote Repo -

- - - gets pushed - - -

- @ R01 - - @ R02 - - @ R02 -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Local Repo - - Local Repo - - Local Repo -

- pull - - - - fetch -

- @ R01 - - @ R01 - - @ R02 -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Local Sandbox - - Local Sandbox - - Local Sandbox -

- Checkout - - new work done - - -

- @ R01 - - @ R01+ - - @R01+ -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

The three repos with a pull

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Remote Repo - - Remote Repo - - Remote Repo -

- - - gets pushed - - -

- @ R01 - - @ R02 - - @ R02 -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Local Repo - - Local Repo - - Local Repo -

- pull - - - - pull -

- @ R01 - - @ R01 - - @ R02 -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

- Local Sandbox - - Local Sandbox - - Local Sandbox -

- Checkout - - new work done - - merged with R02 -

- @ R01 - - @ R01+ - - @R02+ -

--------------------- ----------------------- -----------------------

This helped me understand why a fetch is pretty important.

In simple terms, if you were about to hop onto a plane without any Internet connection… before departing you could just do git fetch origin <branch>. It would fetch all the changes into your computer, but keep it separate from your local development/workspace.

On the plane, you could make changes to your local workspace and then merge it with what you've previously fetched and then resolve potential merge conflicts all without a connection to the Internet. And unless someone had made new changes to the remote repository then, upon arrive at the destination you would do git push origin <branch> and go get your coffee.

From this awesome Atlassian tutorial:

The

git fetchcommand downloads commits, files, and refs from a remote repository into your local repository.Fetching is what you do when you want to see what everybody else has been working on. It’s similar to SVN update in that it lets you see how the central history has progressed, but it doesn’t force you to actually merge the changes into your repository. Git isolates fetched content as a from existing local content, it has absolutely no effect on your local development work. Fetched content has to be explicitly checked out using the

git checkoutcommand. This makes fetching a safe way to review commits before integrating them with your local repository.When downloading content from a remote repository,

git pullandgit fetchcommands are available to accomplish the task. You can considergit fetchthe 'safe' version of the two commands. It will download the remote content, but not update your local repository's working state, leaving your current work intact.git pullis the more aggressive alternative, it will download the remote content for the active local branch and immediately executegit mergeto create a merge commit for the new remote content. If you have pending changes in progress this will cause conflicts and kickoff the merge conflict resolution flow.

With git pull:

- You don't get any isolation.

- It doesn't need to be explicitly checked out. Because it implicitly does a

git merge. - The merging step will affect your local development and may cause conflicts

- It's basically NOT safe. It's aggressive.

- Unlike

git fetchwhere it only affects your.git/refs/remotes, git pull will affect both your.git/refs/remotesand.git/refs/heads/

Hmmm...so if I'm not updating the working copy with git fetch, then where am I making changes? Where does Git fetch store the new commits?

Great question. First and foremost, the heads or remotes don't store the new commits. They just have pointers to commits. So with git fetch you download the latest git objects (blob, tree, commits. To fully understand the objects watch this video on git internals), but only update your remotes pointer to point to the latest commit of that branch. It's still isolated from your working copy, because your branch's pointer in the heads directory hasn't updated. It will only update upon a merge/pull. But again where? Let's find out.

In your project directory (i.e., where you do your git commands) do:

ls. This will show the files & directories. Nothing cool, I know.Now do

ls -a. This will show dot files, i.e., files beginning with.You will then be able to see a directory named:.git.Do

cd .git. This will obviously change your directory.Now comes the fun part; do

ls. You will see a list of directories. We're looking forrefs. Docd refs.It's interesting to see what's inside all directories, but let's focus on two of them.

headsandremotes. Usecdto check inside them too.Any

git fetchthat you do will update the pointer in the/.git/refs/remotesdirectory. It won't update anything in the/.git/refs/headsdirectory.Any

git pullwill first do thegit fetchand update items in the/.git/refs/remotesdirectory. It will then also merge with your local and then change the head inside the/.git/refs/headsdirectory.

A very good related answer can also be found in Where does 'git fetch' place itself?.

Also, look for "Slash notation" from the Git branch naming conventions post. It helps you better understand how Git places things in different directories.

To see the actual difference

Just do:

git fetch origin master

git checkout master

If the remote master was updated you'll get a message like this:

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 2 commits, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

If you didn't fetch and just did git checkout master then your local git wouldn't know that there are 2 commits added. And it would just say:

Already on 'master'

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

But that's outdated and incorrect. It's because git will give you feedback solely based on what it knows. It's oblivious to new commits that it hasn't pulled down yet...

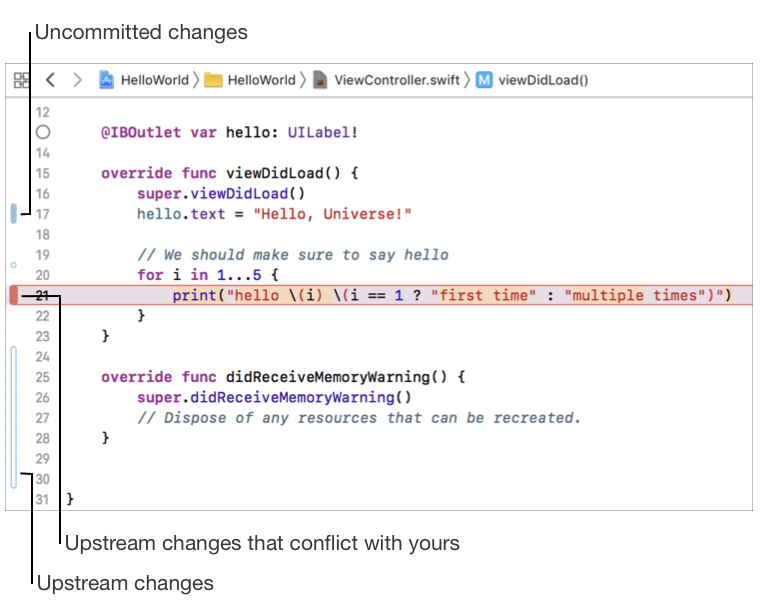

Is there any way to see the new changes made in remote while working on the branch locally?

Some IDEs (e.g. Xcode) are super smart and use the result of a git fetch and can annotate the lines of code that have been changed in remote branch of your current working branch. If that line has been changed by both local changes and remote branch, then that line gets annotated with red. This isn't a merge conflict. It's a potential merge conflict. It's a headsup that you can use to resolve the future merge conflict before doing git pull from the remote branch.

Fun tip:

If you fetched a remote branch e.g. did:

git fetch origin feature/123

Then this would go into your remotes directory. It's still not available to your local directory. However, it simplifies your checkout to that remote branch by DWIM (Do what I mean):

git checkout feature/123

you no longer need to do:

git checkout -b feature/123 origin/feature/123

For more on that read here

We simply say:

git pull == git fetch + git merge

If you run git pull, you do not need to merge the data to local. If you run git fetch, it means you must run git merge for getting the latest code to your local machine. Otherwise, the local machine code would not be changed without merge.

So in the Git Gui, when you do fetch, you have to merge the data. Fetch itself won't make the code changes at your local. You can check that when you update the code by fetching once fetch and see; the code it won't change. Then you merge... You will see the changed code.

git fetch pulls down the code from the remote server to your tracking branches in your local repository. If your remote is named origin (the default) then these branches will be within origin/, for example origin/master, origin/mybranch-123, etc. These are not your current branches, they are local copies of those branches from the server.

git pull does a git fetch but then also merges the code from the tracking branch into your current local version of that branch. If you're not ready for that changes yet, just git fetch first.

git fetch will retrieve remote branches so that you can git diff or git merge them with the current branch. git pull will run fetch on the remote brach tracked by the current branch and then merge the result. You can use git fetch to see if there are any updates to the remote branch without necessary merging them with your local branch.

Git Fetch

You download changes to your local branch from origin through fetch. Fetch asks the remote repo for all commits that others have made but you don't have on your local repo. Fetch downloads these commits and adds them to the local repository.

Git Merge

You can apply changes downloaded through fetch using the merge command. Merge will take the commits retrieved from fetch and try to add them to your local branch. The merge will keep the commit history of your local changes so that when you share your branch with push, Git will know how others can merge your changes.

Git Pull

Fetch and merge run together often enough that a command that combines the two, pull, was created. Pull does a fetch and then a merge to add the downloaded commits into your local branch.

The only difference between git pull and git fetch is that :

git pull pulls from a remote branch and merges it.

git fetch only fetches from the remote branch but it does not merge

i.e. git pull = git fetch + git merge ...

The git pull command is actually a shortcut for git fetch followed by the git merge or the git rebase command depending on your configuration. You can configure your Git repository so that git pull is a fetch followed by a rebase.

Git allows chronologically older commits to be applied after newer commits. Because of this, the act of transferring commits between repositories is split into two steps:

Copying new commits from remote branch to copy of this remote branch inside local repo.

(repo to repo operation)

master@remote >> remote/origin/master@localIntegrating new commits to local branch

(inside-repo operation)

remote/origin/master@local >> master@local

There are two ways of doing step 2. You can:

- Fork local branch after last common ancestor and add new commits parallel to commits which are unique to local repository, finalized by merging commit, closing the fork.

- Insert new commits after last common ancestor and reapply commits unique to local repository.

In git terminology, step 1 is git fetch, step 2 is git merge or git rebase

git pull is git fetch and git merge

What is the difference between

git pullandgit fetch?

To understand this, you first need to understand that your local git maintains not only your local repository, but it also maintains a local copy of the remote repository.

git fetch brings your local copy of the remote repository up to date. For example, if your remote repository is GitHub - you may want to fetch any changes made in the remote repository to your local copy of it the remote repository. This will allow you to perform operations such as compare or merge.

git pull on the other hand will bring down the changes in the remote repository to where you keep your own code. Typically, git pull will do a git fetch first to bring the local copy of the remote repository up to date, and then it will merge the changes into your own code repository and possibly your working copy.

Git obtains the branch of the latest version from the remote to the local using two commands:

git fetch: Git is going to get the latest version from remote to local, but it do not automatically merge.

git fetch origin mastergit log -p master..origin/mastergit merge origin/masterThe commands above mean that download latest version of the main branch from origin from the remote to origin master branch. And then compares the local master branch and origin master branch. Finally, merge.

git pull: Git is going to get the latest version from the remote and merge into the local.

git pull origin masterThe command above is the equivalent to

git fetchandgit merge. In practice,git fetchmaybe more secure because before the merge we can see the changes and decide whether to merge.

A simple Graphical Representation for Beginners,

here,

git pull

will fetch code from repository and rebase with your local... in git pull there is possibility of new commits getting created.

but in ,

git fetch

will fetch code from repository and we need to rebase it manually by using git rebase

eg: i am going to fetch from server master and rebase it in my local master.

1) git pull ( rebase will done automatically):

git pull origin master

here origin is your remote repo master is your branch

2) git fetch (need to rebase manually):

git fetch origin master

it will fetch server changes from origin. and it will be in your local until you rebase it on your own. we need to fix conflicts manually by checking codes.

git rebase origin/master

this will rebase code into local. before that ensure you're in right branch.

Actually Git maintains a copy of your own code and the remote repository.

The command git fetch makes your local copy up to date by getting data from remote repository. The reason we need this is because somebody else might have made some changes to the code and you want to keep yourself updated.

The command git pull brings the changes in the remote repository to where you keep your own code. Normally, git pull does this by doing a ‘git fetch’ first to bring the local copy of the remote repository up to date, and then it merges the changes into your own code repository and possibly your working copy.

git pull == ( git fetch + git merge)

git fetch does not changes to local branches.

If you already have a local repository with a remote set up for the desired project, you can grab all branches and tags for the existing remote using git fetch . ... Fetch does not make any changes to local branches, so you will need to merge a remote branch with a paired local branch to incorporate newly fetch changes. from github

git pull

It performs two functions using a single command.

It fetches all the changes that were made to the remote branch and then merges those changes into your local branch. You can also modify the behaviour of pull by passing --rebase. The difference between merge and rebase can be read here

git fetch

Git fetch does only half the work of git pull. It just brings the remote changes into your local repo but does not apply them onto your branches.You have to explicitly apply those changes. This can be done as follows:

git fetch

git rebase origin/master

One must keep in mind the nature of git. You have remotes and your local branches ( not necessarily the same ) . In comparison to other source control systems this can be a bit perplexing.

Usually when you checkout a remote a local copy is created that tracks the remote.

git fetch will work with the remote branch and update your information.

It is actually the case if other SWEs are working one the same branch, and rarely the case in small one dev - one branch - one project scenarios.

Your work on the local branch is still intact. In order to bring the changes to your local branch you have to merge/rebase the changes from the remote branch.

git pull does exactly these two steps ( i.e. --rebase to rebase instead of merge )

If your local history and the remote history have conflicts the you will be forced to do the merge during a git push to publish your changes.

Thus it really depends on the nature of your work environment and experience what to use.

All branches are stored in .git/refs

All local branches are stored in .git/refs/heads

All remote branches are stored in .git/refs/remotes

The

git fetchcommand downloads commits, files, and refs from a remote repository into your local repo. Fetching is what you do when you want to see what everybody else has been working on.

So when you do git fetch all the files, commits, and refs are downloaded in

this directory .git/refs/remotes

You can switch to these branches to see the changes.

Also, you can merge them if you want.

git pulljust downloads these changes and also merges them to the current branch.

Example

If you want see the work of remote branch dev/jd/feature/auth, you just need to do

git fetch origin dev/jd/feature/auth

to see the changes or work progress do,

git checkout dev/jd/feature/auth

But, If you also want to fetch and merge them in the current branch do,

git pull origin dev/jd/feature/auth

If you do git fetch origin branch_name, it will fetch the branch, now you can switch to this branch you want and see the changes. Your local master or other local branches won't be affected. But git pull origin branch_name will fetch the branch and will also merge to the current branch.

Simple explanation:

git fetch

fetches the metadata. If you want to check out a recently created branch you may want to do a fetch before checkout.

git pull

Fetches the metadata from remote and also moved the files from remote and merge on to the branch

Git Fetch

Helps you to get known about the latest updates from a git repository. Let's say you working in a team using GitFlow, where team working on multiple branches ( features ). With git fetch --all command you can get known about all new branches within repository.

Mostly git fetch is used with git reset. For example you want to revert all your local changes to the current repository state.

git fetch --all // get known about latest updates

git reset --hard origin/[branch] // revert to current branch state

Git pull

This command update your branch with current repository branch state. Let's continue with GitFlow. Multiple feature branches was merged to develop branch and when you want to develop new features for the project you must go to the develop branch and do a git pull to get the current state of develop branch

Documentation for GitFlow https://gist.github.com/peterdeweese/4251497

git merge is a local operation that only affects your working copy. –

Disloyalty © 2022 - 2024 — McMap. All rights reserved.

git fetch; git reset --hard origin/masteras part of our workflow. It blows away local changes, keeps you up to date with master BUT makes sure you don't just pull in new changes on top on current changes and make a mess. We've used it for a while and it basically feels a lot safer in practice. Just be sure to add/commit/stash any work-in-progress first ! – Winne