They make the most sense to me with an example...

Examining layers of your own build with docker diff

Lets take a contrived example Dockerfile:

FROM busybox

RUN mkdir /data

# imagine this is downloading source code

RUN dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/one

RUN chmod -R 0777 /data

# imagine this is compiling the app

RUN dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/two

RUN chmod -R 0777 /data

# and now this cleans up that downloaded source code

RUN rm /data/one

CMD ls -alh /data

Each of those dd commands outputs a 1M file to the disk. Lets build the image with an extra flag to save the temporary containers:

docker image build --rm=false .

In the output, you'll see each of the running commands happen in a temporary container that we now keep instead of automatically deleting:

...

Step 2/7 : RUN mkdir /data

---> Running in 04c5fa1360b0

---> 9b4368667b8c

Step 3/7 : RUN dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/one

---> Running in f1b72db3bfaa

1024+0 records in

1024+0 records out

1048576 bytes (1.0MB) copied, 0.006002 seconds, 166.6MB/s

---> ea2506fc6e11

If you run a docker diff on each of those container id's, you'll see what files were created in those containers:

$ docker diff 04c5fa1360b0 # mkdir /data

A /data

$ docker diff f1b72db3bfaa # dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/one

C /data

A /data/one

$ docker diff 81c607555a7d # chmod -R 0777 /data

C /data

C /data/one

$ docker diff 1bd249e1a47b # dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/two

C /data

A /data/two

$ docker diff 038bd2bc5aea # chmod -R 0777 /data

C /data/one

C /data/two

$ docker diff 504c6e9b6637 # rm /data/one

C /data

D /data/one

Each line prefixed with an A is adding the file, the C indicates a change to an existing file, and the D indicates a delete.

Here's the TL;DR part

Each of these container filesystem diffs above goes into one "layer" that gets assembled when you run the image as a container. The entire file is in each layer when there's an add or change, so each of those chmod commands, despite just changing a permission bit, results in the entire file being copied into the next layer. The deleted /data/one file is still in the previous layers, 3 times in fact, and will be copied over the network and stored on disk when you pull the image.

Examining existing images

You can see the commands that goes into creating the layers of an existing image with the docker history command. You can also run a docker image inspect on an image and see the list of layers under the RootFS section.

Here's the history for the above image:

IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY SIZE COMMENT

a81cfb93008c 4 seconds ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["/bin/sh" "-c" "ls -… 0B

f36265598aef 5 seconds ago /bin/sh -c rm /data/one 0B

c79aff033b1c 7 seconds ago /bin/sh -c chmod -R 0777 /data 2.1MB

b821dfe9ea38 10 seconds ago /bin/sh -c dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=102… 1.05MB

a5602b8e8c69 13 seconds ago /bin/sh -c chmod -R 0777 /data 1.05MB

08ec3c707b11 15 seconds ago /bin/sh -c dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=102… 1.05MB

ed27832cb6c7 18 seconds ago /bin/sh -c mkdir /data 0B

22c2dd5ee85d 2 weeks ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["sh"] 0B

<missing> 2 weeks ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) ADD file:2a4c44bdcb743a52f… 1.16MB

The newest layers are listed on top. Of note, there are two layers at the bottom that are fairly old. They come from the busybox image itself. When you build one image, you inherit all the layers of the image you specify in the FROM line. There are also layers being added for changes to the image meta-data, like the CMD line. They barely take up any space and are more for record keeping of what settings apply to the image you are running.

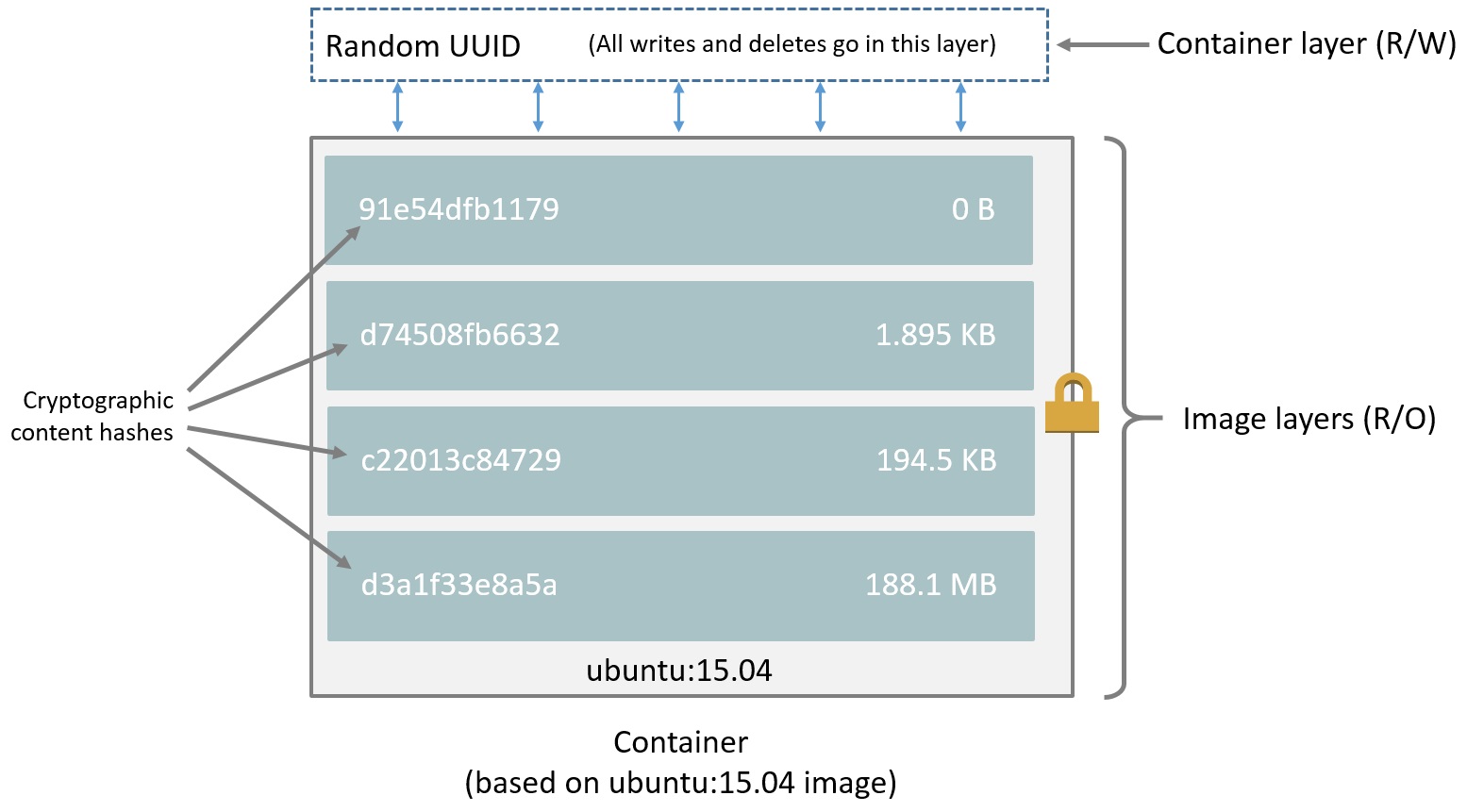

Why layers?

The layers have a couple advantages. First, they are immutable. Once created, that layer identified by a sha256 hash will never change. That immutability allows images to safely build and fork off of each other. If two dockerfiles have the same initial set of lines, and are built on the same server, they will share the same set of initial layers, saving disk space. That also means if you rebuild an image, with just the last few lines of the Dockerfile experiencing changes, only those layers need to be rebuilt and the rest can be reused from the layer cache. This can make a rebuild of docker images very fast.

Inside a container, you see the image filesystem, but that filesystem is not copied. On top of those image layers, the container mounts it's own read-write filesystem layer. Every read of a file goes down through the layers until it hits a layer that has marked the file for deletion, has a copy of the file in that layer, or the read runs out of layers to search through. Every write makes a modification in the container specific read-write layer.

Reducing layer bloat

One downside of the layers is building images that duplicate files or ship files that are deleted in a later layer. The solution is often to merge multiple commands into a single RUN command. Particularly when you are modifying existing files or deleting files, you want those steps to run in the same command where they were first created. A rewrite of the above Dockerfile would look like:

FROM busybox

RUN mkdir /data \

&& dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/one \

&& chmod -R 0777 /data \

&& dd if=/dev/zero bs=1024 count=1024 of=/data/two \

&& chmod -R 0777 /data \

&& rm /data/one

CMD ls -alh /data

And if you compare the resulting images:

- busybox: ~1MB

- first image: ~6MB

- second image: ~2MB

Just by merging together some lines in the contrived example, we got the same resulting content in our image, and shrunk our image from 5MB to just the 1MB file that you see in the final image.