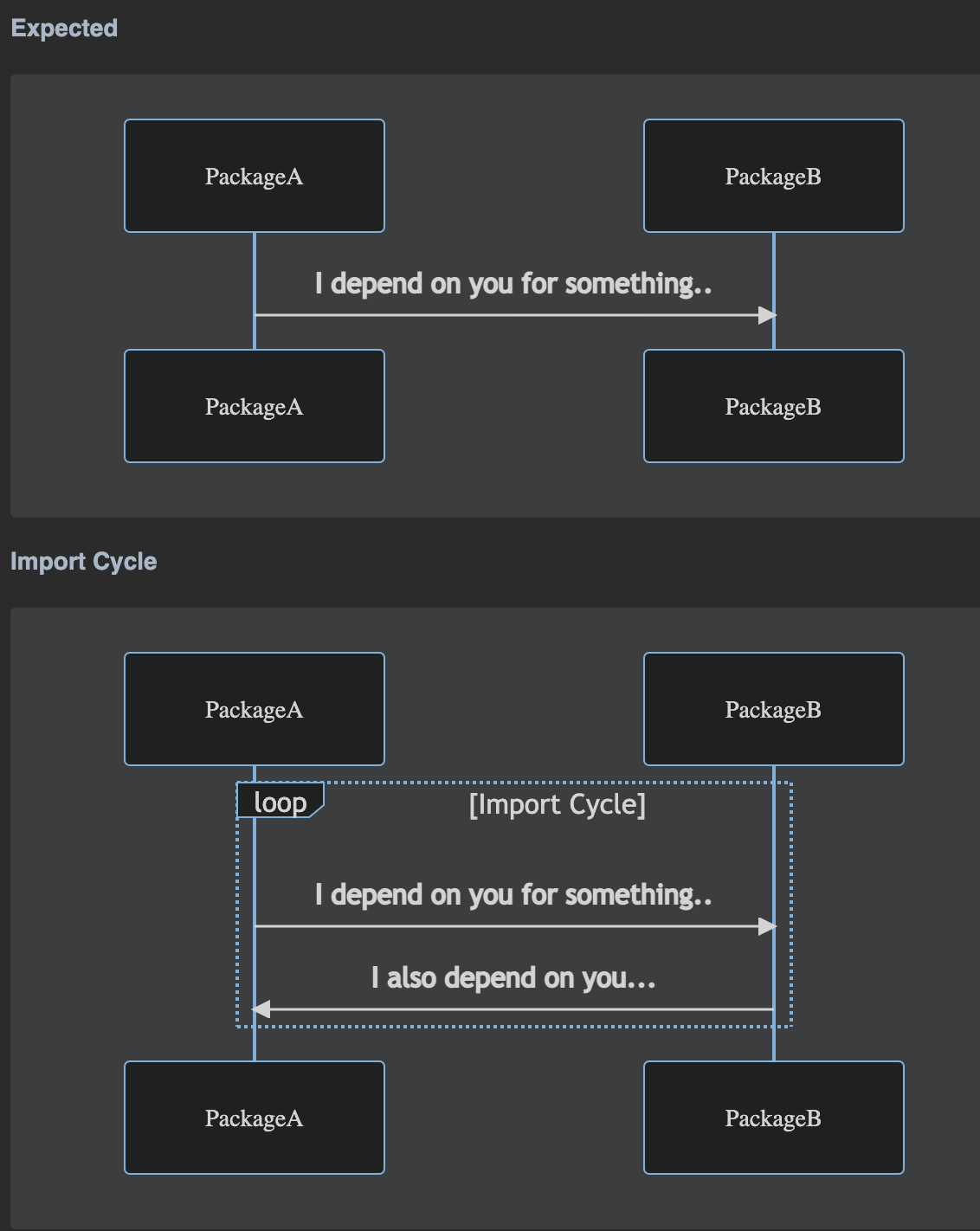

So I have this import cycle which I'm trying to solve. I have this following pattern:

view/

- view.go

action/

- action.go

- register.go

And the general idea is that actions are performed on a view, and are executed by the view:

// view.go

type View struct {

Name string

}

// action.go

func ChangeName(v *view.View) {

v.Name = "new name"

}

// register.go

const Register = map[string]func(v *view.View) {

"ChangeName": ChangeName,

}

And then in view.go we invoke this:

func (v *View) doThings() {

if action, exists := action.Register["ChangeName"]; exists {

action(v)

}

}

But this causes a cycle because View depends on the Action package, and vice versa. How can I solve this cycle? Is there a different way to approach this?