The yield keyword allows you to create an IEnumerable<T> in the form on an iterator block. This iterator block supports deferred executing and if you are not familiar with the concept it may appear almost magical. However, at the end of the day it is just code that executes without any weird tricks.

An iterator block can be described as syntactic sugar where the compiler generates a state machine that keeps track of how far the enumeration of the enumerable has progressed. To enumerate an enumerable, you often use a foreach loop. However, a foreach loop is also syntactic sugar. So you are two abstractions removed from the real code which is why it initially might be hard to understand how it all works together.

Assume that you have a very simple iterator block:

IEnumerable<int> IteratorBlock()

{

Console.WriteLine("Begin");

yield return 1;

Console.WriteLine("After 1");

yield return 2;

Console.WriteLine("After 2");

yield return 42;

Console.WriteLine("End");

}

Real iterator blocks often have conditions and loops but when you check the conditions and unroll the loops they still end up as yield statements interleaved with other code.

To enumerate the iterator block a foreach loop is used:

foreach (var i in IteratorBlock())

Console.WriteLine(i);

Here is the output (no surprises here):

Begin

1

After 1

2

After 2

42

End

As stated above foreach is syntactic sugar:

IEnumerator<int> enumerator = null;

try

{

enumerator = IteratorBlock().GetEnumerator();

while (enumerator.MoveNext())

{

var i = enumerator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(i);

}

}

finally

{

enumerator?.Dispose();

}

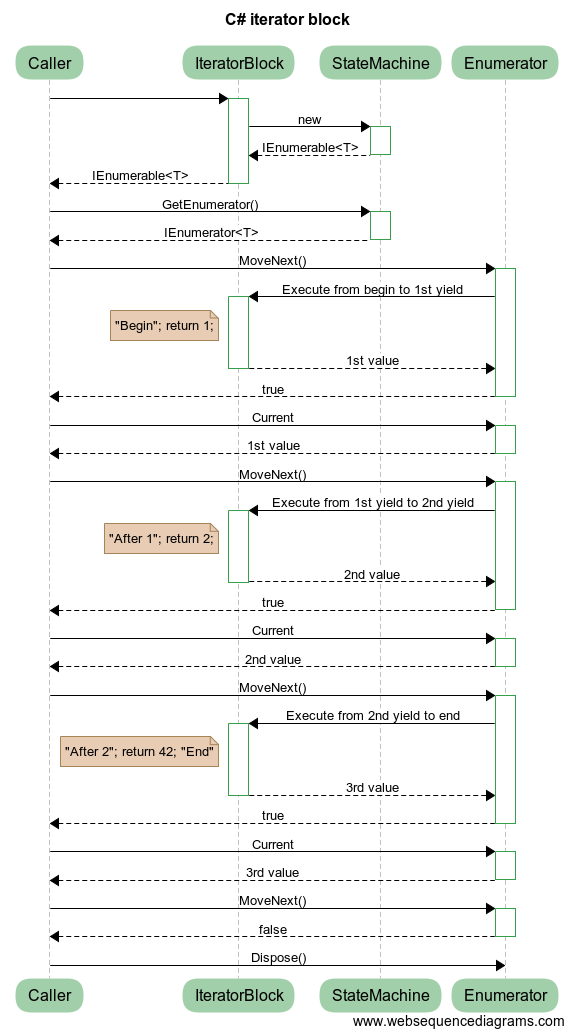

In an attempt to untangle this I have crated a sequence diagram with the abstractions removed:

![C# iterator block sequence diagram]()

The state machine generated by the compiler also implements the enumerator but to make the diagram more clear I have shown them as separate instances. (When the state machine is enumerated from another thread you do actually get separate instances but that detail is not important here.)

Every time you call your iterator block a new instance of the state machine is created. However, none of your code in the iterator block is executed until enumerator.MoveNext() executes for the first time. This is how deferred executing works. Here is a (rather silly) example:

var evenNumbers = IteratorBlock().Where(i => i%2 == 0);

At this point the iterator has not executed. The Where clause creates a new IEnumerable<T> that wraps the IEnumerable<T> returned by IteratorBlock but this enumerable has yet to be enumerated. This happens when you execute a foreach loop:

foreach (var evenNumber in evenNumbers)

Console.WriteLine(eventNumber);

If you enumerate the enumerable twice then a new instance of the state machine is created each time and your iterator block will execute the same code twice.

Notice that LINQ methods like ToList(), ToArray(), First(), Count() etc. will use a foreach loop to enumerate the enumerable. For instance ToList() will enumerate all elements of the enumerable and store them in a list. You can now access the list to get all elements of the enumerable without the iterator block executing again. There is a trade-off between using CPU to produce the elements of the enumerable multiple times and memory to store the elements of the enumeration to access them multiple times when using methods like ToList().